|    |    |    |    |   |

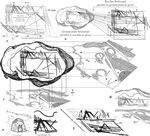

| Figure 1. Straight

edge theory: Artifacts 1–3. Note: The Artifacts 1–6

numbering system is from Mania and Mania 2005. Rulers were superimposed

by J. Feliks. (a & c) Detail, Artifact 1 engravings cropped from

photograph by R. Bednarik 1997. Used with permission. Artifact 1 is the

tibia bone of a straight-tusked elephant. (b) Artifact 1 after Mania

and Mania 1988. (d) Artifact 2, the rib bone of a large mammal, after

Mania and Mania 1988. (e) Detail, Artifact 2 engravings showing

duplicated 3-part compound motifs, cropped from photograph by Mania and

Mania 1988. Used with permission. (f) Artifact 3 after Mania and Mania

1988. (g) Close-up, double-engraved lines of Artifact 3. |

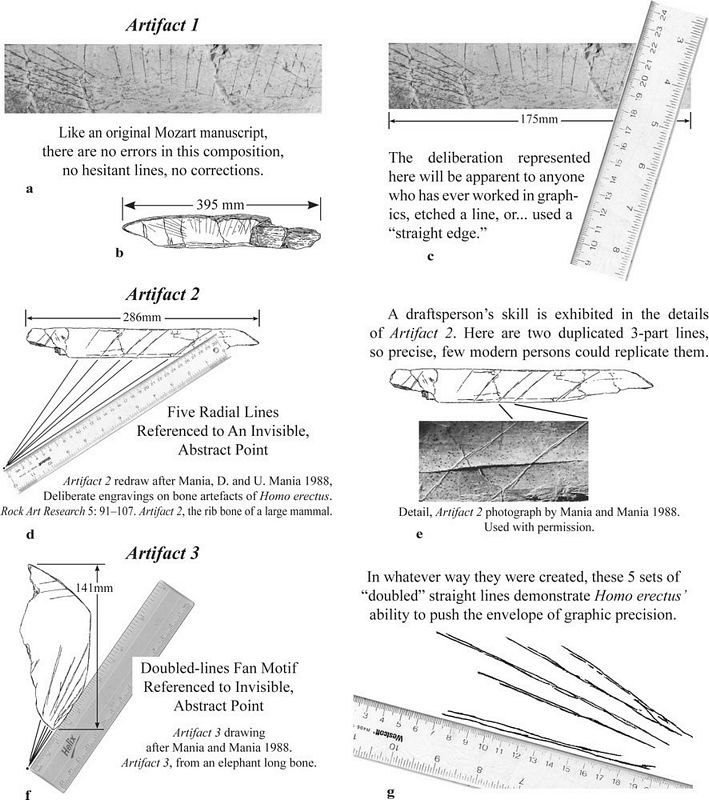

| Figure 2. Fig. 7.2. Straight edge theory, Artifacts 3–6. (a) Detail, Artifact 3, highlighting

an unambiguously straight engraved angle tapered at less than 2�

and comparable to modern standards of quality. Photograph by Mania and

Mania 1988. Used with permission.

(b) Artifact 4, a flat piece of bone, after Mania and Mania

1988. (c) Detail, Artifact 4 photograph, Mania and Mania 1988. (d)

Extreme close-up, Artifact 4 photograph. Mania and Mania 1988. Used

with permission. (e) Artifact 5. Bednarik 1995. Certainly, straight

lines engraved on a slab of stone cannot be explained away as

survival behavior. Used with permission. (f) Artifact 6. This work

represents either simple musings by someone fascinated with straight

lines and trig angles or a highly purposeful arrangement. (g)

Engravings from Artifact 6 isolated—highlighting presence of the

special trig angles 30, 45, 60, 90; parallels, diagonals, perpendiculars, and planes—all within �3� deviation.

Apart from a few slight curves, the draftsmanship consists entirely of

straight lines likely drawn with an edge. “Non-obvious parallel

etchings” were bolded and color-coded. |

|

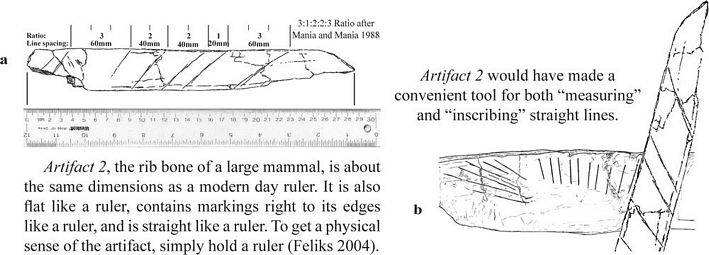

Figure 3. Proposed early straight edge. (a) Artifact 2 compared with a

modern ruler. (b) Proposed early straight edge in use. (Artifact 2

after Mania and Mania 1988, Artifact 1 drawing after photograph by R.

Bednarik 1997.). |

|

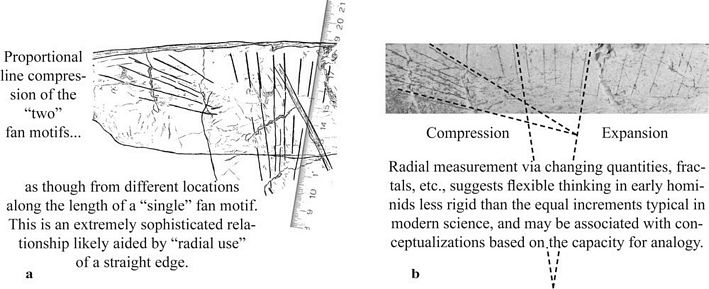

Figure 4. Straight edge theory and the “Realm of Ideas.” (a)

Proportional line compression of “two” fan motifs as though

from different locations along the length of a “single”

fan motif. Referring to Plato’s “realm of ideas” or

“theory of forms,” the two motifs in Artifact 1 suggest an

awareness of the fan shape or radial image in a way that transcends

simple observation of the physical world or as writers such as Morris

(1962) or Gowlett (1984) might refer to as a “mental

template.” (b) Compression-expansion and one means by which

radial measurement (or ratio measurement as in the Part 2 paper) can be

a geometric equivalent of analogy (Artifact 1 drawing after photograph

by Bednarik 1997, Detail Artifact 1 cropped from photograph by R.

Bednarik 1997. Used with permission.). |

|

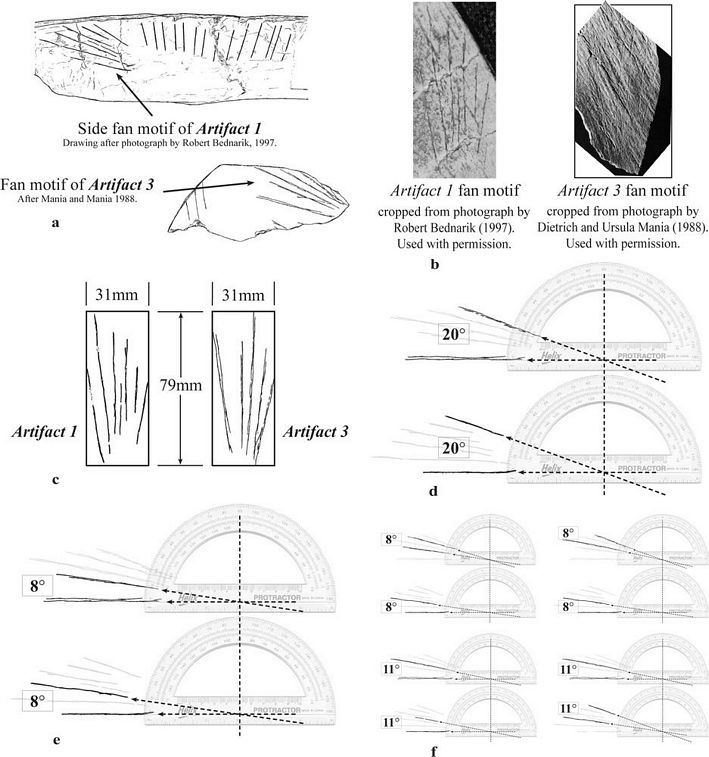

Figure 5.The

earliest motif duplicated on two separate artifacts. Part 1. (a) The

motifs in context with other syntactic variables. (b) Photographs. (c)

Observation 1: The motifs are the same size. (d) Observation 2: The

motifs share “identical” outer angles. (e) Observation 3:

The motifs share identical “inner” angles. (f) Observation

4: The motifs share many other identical angles. Beyond the angles

detailed in this paper, there are at least 5 more near identical angles

and more than 10 other angles that are within one degree of each other.

The difference with these additional angles is that they do not share

the same radial points. |

|

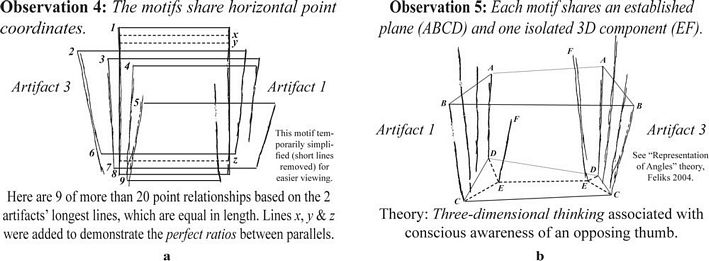

Figure 6. The earliest motif duplicated on two separate artifacts, Part 2. In

each of these studies, the two smallest lines of Artifact 1 have been

hidden so as to make the similarities readily visible. The effects

demonstrated here remain the same with or without the two smaller

lines. Even though graphics are usually laid out in two dimensions,

they reflect the internal world of three-dimensional thinking. 3D

studies offer access to the three-dimensional mind of Palaeolithic

peoples. (a) Although the two motifs appear different on the surface,

when they are compared via a Cartesian grid approach, they are each

seen to account for “most” of the same points, merely by

different means. (The effect of how things can appear quite different

on the surface yet be quite alike on a fundamental level is easy to

grasp when one compares a scallop shell, for instance, with an octopus.

Although completely different in external appearance they are closely

related internally, and are each classified as mollusks.) (b) Comparing

and interpreting two lines (each labeled EF) as positioned on

“separate planes” from the other lines in each set

(collectively labeled ABCD and interpreted as defining two planes). |

|

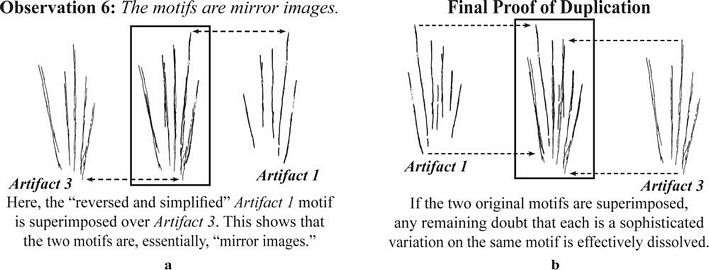

Figure 7.

The earliest motif duplicated on two separate artifacts, Part 3. (a)

The two motifs superimposed with the Artifact 1 motif flipped in

reverse. (b) The two motifs, with all lines present, superimposed

according to their standard orientation. One way to test the veracity

of the duplicated motif theory is to find out if any modern persons

could duplicate such precision as indicated here. Computers aside, I

propose that even in modern times these two motifs could not be

duplicated this accurately without a straight edge or protractor and

reference to the other image or its outer angle and vertex. |

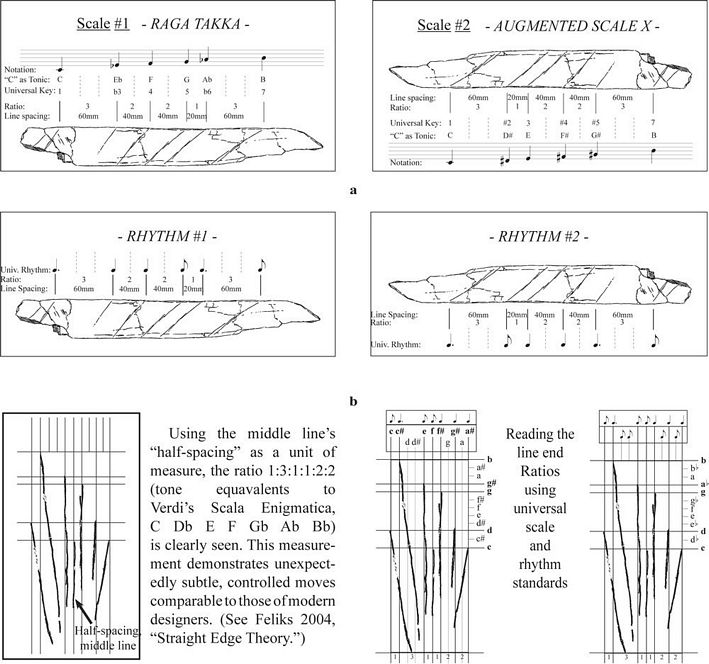

| Figure 8. 350,000

years before Bach. Reading the mathematical ratios by way of universal

key and rhythm standards. These studies were inspired by Mania and

Mania’s 1988 discovery of a mathematical ratio in the Artifact 2

engravings, namely, 3:1:2:2:3. As explained in a prior paper (Feliks

2006), these ratios are applicable to the concepts of pitch, rhythm,

and syntax in Palaeothic language. (a) Artifact 2 musical scales and

rhythms, only a few examples. (b) Artifact 1 side-fan motif “line

end ratios,” measuring the ratios by universal key and rhythm

standards. Note: spacing of vertical lines in these studies was

“tempered” for easier viewing. The tolerances applied are

clearly visible and are used for this interpretation only; they are not

suggested as the only interpretation. The deviations are within 2%,

inconsequential by archaeological standards. Side-fan motif redrawn

after photograph by R. Bednarik 1997. |

|

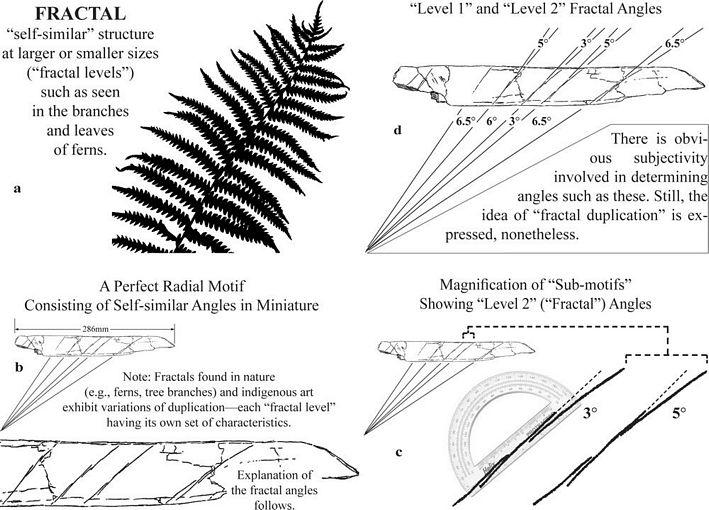

Figure 9. Fractal angle symmetry. (a)

Definition of fractal, with natural world example: living fern scan

(Feliks 1998). (b) Two views of Artifact 2 radial motif showing

“Level 1” angles (upper image) consisting of sub-motif

self-similar “Level 2” angles (lower image). Awareness of

fractals is a geometric equivalent to awareness of analogy. (c)

“Magnification of sub-motifs showing “Level 2”

fractal angles in Artifact 2. Very notable is the engraved 3�

angle. As with the 2� angle of Fig. 2a, a 3� angle is stunning

by any standards. (d) “Level 1” and “Level 2”

fractal angles in Artifact 2. These self-similar angles exhibit even

more sophisticated variations than detailed here such as diminution and

augmentation (Feliks 2008: Figures 8, 9, and 18). Most of the math

regarding fractals has only been developed during the past 25 years.

However, roots in ancient Africa are now known (e.g., Eglash 1999).

Artifact 2 drawing after Mania and Mania 1988. |

|

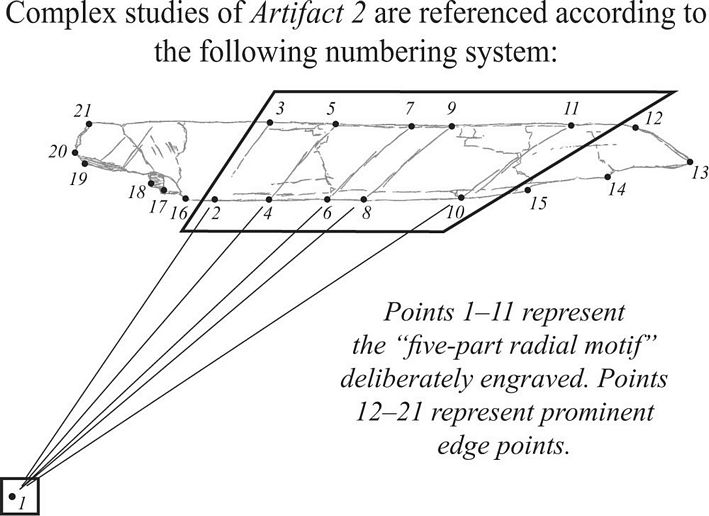

Figure 10. Numbering

system for the radial motif of Artifact 2. Lines which do not

participate in the radial motif are not focused upon in this particular

series. If the two small engraved lines at the left side of Artifact 2

are needed, their points may be referred to as 18a, 18b, and 21a, 21b. |

|

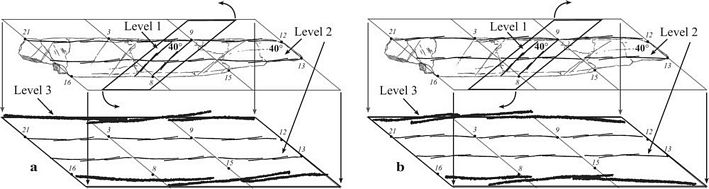

Figure 11. Three-level,

self-similarity fractal characterized by parallels in thirds.

Interpreting components of the central double-motif as parallel rather

than subtly radial, they are seen to perfectly echo the structure and

basic angles of the entire artifact—whether rotated left or

rotated right. Level 1 is the doubled composite motif. Level 2 is the

motif duplicated three times in a row where it is seen to align

perfectly with parallels 21-16, 3-8, 9-15 and 12-13. Level 3 is the

double composite motif enlarged to the length of the entire artifact,

at which point it is seen to still align with these very same

parallels. While seeming like an inexplicable puzzle, it is simply more

evidence of fractal mental structure in Homo erectus, the acceptance of

which will be indispensable in understanding their language

capabilities. It is notable that this interpretation works whether the

motif is rotated to the left or rotated to the right. In Bach’s

famous Art of the Fugue (his final work), Contrapunctus XII and XIII

are known as “mirror fugues,” working equally well played

forward or backward. Also, one of the mirrors is

“upside-down,” while the other is a syntax inversion (see

Part III). This same level of mathematical symmetry was also

demonstrated by the radial motifs of Bilzingsleben Artifacts 1 & 3

(Fig. 7), that matched each other whether superimposed in standard

positioning or as mirror images. (a) left rotation. (b) right rotation. |

|

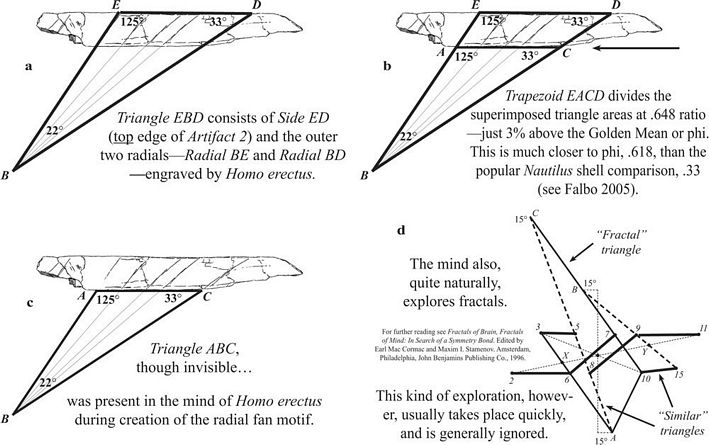

Figure 12. Invisible

shapes. All angle measurements are based on the original drawing by

Mania and Mania 1988. (a) Radial motif of Artifact 2 pointing to

invisible vertex, and defining a triangle. (b) Bottom edge of Artifact 2

divides the triangle into a smaller “fractal triangle” and

a trapezoid. (c) The earliest completely abstract and measurable

two-dimensional shape. (d) Excerpt from symmetric asymmetry studies.

This one shows fractal extensions from the Artifact 2 central doubled

motif, the same motif as in Fig. 11. |

|

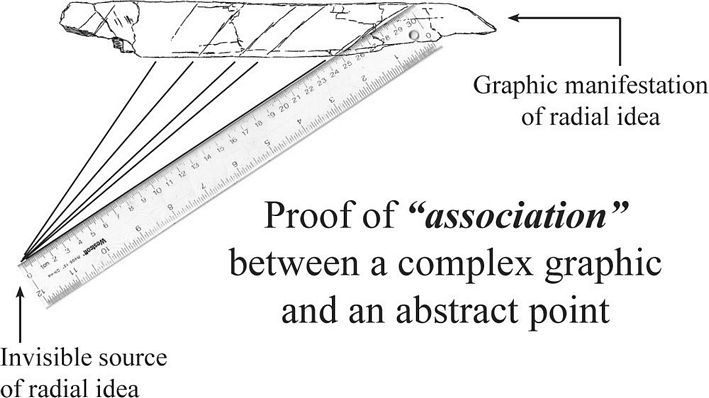

Figure 13. Proof

of association between a complex graphic and an abstract point.

Explanation: First, the primary engravings of Artifact 2 consist of

repeating and varying composite fractal elements (see Figures 9, 11,

and 14) which form a larger radial motif by way of self-similar fractal

angles; this is what makes it a “complex” graphic. Second,

the radial motif is traced backwards to an invisible point in space.

This study suggests that the abstraction abilities necessary for

complex language in which an arbitrary word stands for something which

is not visually or audibly similar was already fully developed by the

time of Bilzingsleben 400,000 years ago. Artifact 2 after Mania and

Mania 1988. |

|

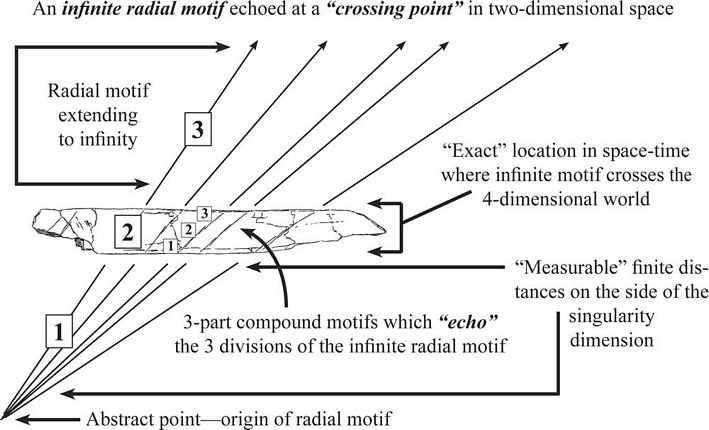

Figure 14. Proof

of association between an abstract point and infinity. As in the

complex works of Bach, which have sometimes been described as hinting

at infinite structures, the 3-part composite nature of the Artifact 2

engravings, likewise, suggest an infinite structure. Put in other

terms, the fractal location of the artifact itself within the infinite

radial motif is suggested by the middle segments of each 3-part

composite line, which appear to have been conceived of as

“breaks” in continuous radial lines, clearly

“in-between” two directions of sight or thought.

Conclusion: The inhabitants of Bilzingsleben were easily capable of

abstract concepts at any level of complexity. |

|

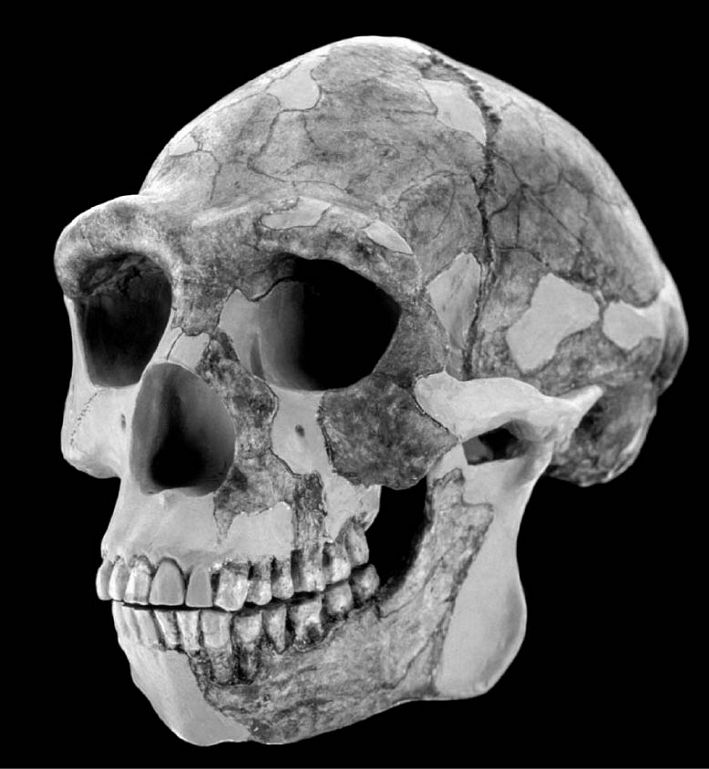

Figure 15. Who

were the people of Bilzingsleben? Putting a face on the Lower

Palaeolithic. In addition to their many shared cultural traits, the

inhabitants of Bilzingsleben were similar in physical appearance to

Homo erectus people living all over the Lower Palaeolithic world in

Africa, China, and Indonesia as far back as 1.7 million years ago

(Vlček 1978, 2002). This is Homo erectus from Zhoukoudian, China, also

known as “Peking Man.” Skull reconstruction by I.

Tattersall and G.J. Sawyer. Photograph courtesy of David Brill. |

|

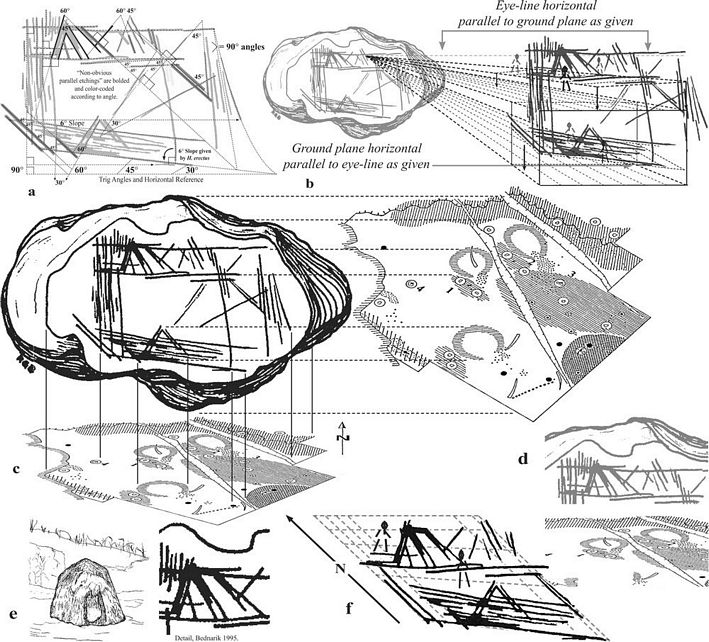

Figure 16. When

a map is a 3D fractal. (a) Non-iconic interpretation of Artifact 6

demonstrates, at the very least, presence of the special trig angles

30, 45, 60, 90; parallels; diagonals; perpendiculars; and

planes—all within �3� deviation, and all likely drawn

with the aid of a straight edge. Trig skills are important in

surveying, mapmaking, navigation, and astronomy. (b) Seeing the planes

as two tiers of a 3D map. If Artifact 6 is a map, it represents a

remarkable solution by H. erectus

to 3D problem. Note that the eye-line horizontal is parallel to the

ground plane (as “given” by H. erectus in the lower

horizontal registration notch labeled “6� Slope” in the

lower right corner of the central square of Fig. 16a; parallel

registration for the upper plane is visible both directly above the

lower registration and to the upper left), theoretically locating the

artist-cartographer in an elevated position, probably about 35 meters

away from the northernmost “huts.” Ground-plane to

eye-line-plane, ground-plane to observer elevation, and

observer-to-huts, are measurable distances using techniques of

trigonometry and a few basic assumptions. Notice other aspects of 3D

perspective style including hut, ground, and angle references, depth

increments (lower plane), occlusion (upper plane), and cardinal

directions. (c) Comparing Artifact 6 (UPPER LEFT, Bednarik 1995) with

angular views of the entire site from the shoreline south as in the

original archaeological map by Mania and Mania 1988. BELOW: Site map

angled to match the lower plane in Artifact 6. RIGHT: Site map angled

to match the hut lines and demonstrate how the entire site is accounted

for (including unanticipated nonrelief [unless the “6�

Slope” and implied position of cartographer are considered]

topographic features) in Artifact 6. (d) Comparing the upper plane of

Artifact 6 with the two northernmost huts in the archaeological map.

The map has been angled to resemble the plane suggested in the

engraving. North orientation is preserved not only in the map, but in

the artifact as well by way of its unambiguously engraved 90�

corner. (e) LEFT: Life-size reconstruction of Bilzingsleben hut (after

photo, Praehistoria Thuringica,

September 2004). RIGHT: Detail from the Artifact 6 sketch perhaps by

someone actually involved in the original hut’s construction,

400,000 years ago. (f) The two planes of Arfitact 6 brought to a single

plane and lined up via the parallel left-right oblique

“registration guides.” As a 2D map, the upper-left right

angles of Artifact 6 are taken as NSEW. In the 3D interpretation, the

“exactly parallel” doubled oblique registration guides are

taken as NS. Remarkably, reading the artifact in this way still matches

NSEW of Mania and Mania’s original archaeological map. |