| The men returned to upstate New York for their wives

and children, and thus word spread particularly among the German community

there. Many other Germans arrived in the decade that followed, and these

newest members of Ann Arbor found solace in their shared tongue. After

first participating in services with other local Protestants, the German

settlers in and around Ann Arbor desired to have a worship service that

they could call their own. The First German Evangelical Society of Scio

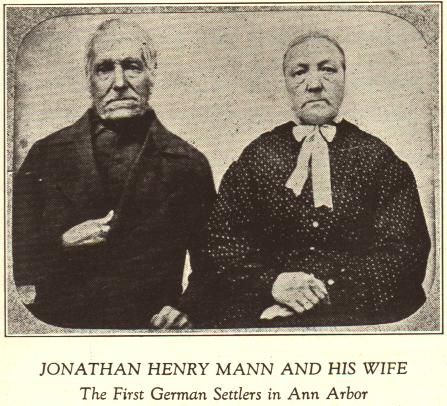

was established when Ann Arborite Jonathan Henry Mann wrote to the Evangelical

Missionary Institute of Basel, Switzerland, for a German-speaking minister

(Stephenson, p.89.) Frederick Schmid's arrival was a triumph for the German

people, who had fled mandatory military service and ethnic persecution

from the French and Austrians (ibid., pp. 82-88.) In 1833, the German community

established the first religious assembly house where they could worship freely in their new American homeland.

Although their desire for a separate German worship temporarily divided

Ann Arbor's spiritual unity, the once-persecuted Germans were avid supporters

of the Union in the Civil War, and the townspeople admired their courage

in the war effort (Stephenson, pp.88-97.) |