In the motley crowd of people that I have met throughout my

life, Sophie Taeuber was the most graceful and the most serene. She

lived like a figure in a prayer book, studious in her work and studious

in her dreaming. The reality of her dreams never foundered in the

reality of days. She was perfectly familiar with both realities. Whether

working in the garden, painting, or preparing for a trip, she would

devote herself to each task with a cheerful zeal and never rest

until she had performed it perfectly. Often I would catch her as she bent

over a table, attentively preparing her colors, carefully wiping the

brush on the edge of the saucer, diligently applying it to the canvas,

piously sketching the lines. Sometimes she would glance up and smile

with charming pride. Day and night were full of marvels for her. She

always looked forward to the coming of evening and dreams. A dream

would continue after she awoke, and at breakfast she would speak

about radiant worlds, sonorous forms, marvelous tales in which roses

and shadows, huge and blazing sun-umbrellas, happy souls and flights

all met in torrents of infinity. Walking with her was unspeakable bliss.

She greeted the world in tranquil joy. Every morning she would visit

her flowers like friends. She spoke to flowers and stars. She spoke

simply to both the tiniest and the largest creatures. She imitated the

chewing of crickets by wrinkling up her nose with amused concentration.

She took the trouble of carrying away in her closed hands the moths that

had strayed around a lamp. I don't know what mysterious intelligence

was exchanged between her and the butterflies. They would always come

hurrying to her; if she stretched out her arm, they would alight upon it;

they settled on her hat, her dress, and rested on her during long walks.

Calmly and precisely she would motion to them; and they would obediently

fly before or after her. She played with these lovely creatures and fled

from them, laughing. The carillon of her laughter was unforgettable.

I met Sophie Taeuber in Zurich in 1915. Even then she already knew

how to give direct and palpable shape to her inner reality. In those

days this kind of art was called "abstract art." Now it is known as

"concrete art," for nothing is more concrete than the psychic reality

that it expresses. Like music, this art is a tangible inner reality.

In the memoirs that the Parisian periodical XXe siècle published,

I wrote: "In 1915 Sophie Taeuber and I painted, embroidered, and did

collages; all these works were drawn from the simplest forms and were

probably the first examples of 'concrete art.' These works are realities,

pure and independent, with no meaning or cerebral intention. We rejected

all mimesis and description, giving free rein to the elementary and the spontaneous."

In 1915 Sophie Taeuber was already dividing the surface of a water

color into squares and rectangles which she juxtaposed horizontally and

perpendicularly. She constructed her painting like a work of masonry.

The colors are luminous, going from rawest yellow to deep red or blue.

In certain compositions she introduces on different levels squat and

massive figures anticipating those she subsequently fashioned in wood.

These figures could blosson into plants, dolls, vases, which in turn

became faces reflecting the dread of solitude and death. But the vigor

of youth, in its richness and brightness, disperses these shadows.

The water colors of the following period (circa 1920) are a

multicolored fabric of innumerable square and rectangular spots. Light

and shadow flourish, and no noisy clash or contrast disturbs the

harmony. Sophie Taeuber was overwhelmed by the feeling of decrepitude,

fragility, and complete inadequacy generated by earthly things. She

rejected the vanity of artistic fakery and saw perfection in humility.

Around 1930 she adopted a mode of composition in squares and

rectangles on a black or white unicolored background. Sometimes she

would introduce triangles or circles. She would often connect these

figures with straight lines and animate them against their white or

black depths with a rising or falling movement or an oscillation, or

else keep them motionless. Her palette knew hardly any colors but

blue, red, yellow and green. She conceived her works in larger

dimensions and did them in oils.

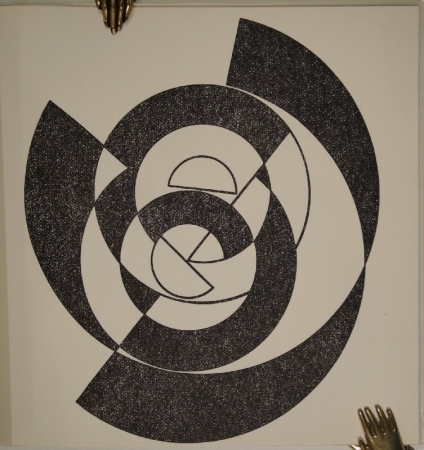

Around 1933 she eliminated straight lines, triangles, rectangles,

squares, and used only circles. The composition always proceeds from a

very strict basic arrangement that, after protracted work, always frees

itself in two or three dots from which the total power of the picture

radiates. They give it its tension and fill it with life and soul.

Several works in that period sometimes contain four or five different

compositions interwoven. These paintings are likewise composed on a

black or white monochrome background. She was painting the chessboard

of night. White, red, and green spheres serve as pawns for the night.

The night plays with the visible and the invisible. The invisible

beats the visible.

From 1936 to 1938 she did a series of wood reliefs. Certain of

these reliefs contain simple groupings of geometric forms,

appliquéd, cut out, or jutting. These reliefs are painted

white, black, red, and blue. The relief entitled Sea-shell

Armor-- vibrant white forms on a rectangular background-- attains

the perfection of beauty. It is with works of this sort that the word

beauty assumes its living sense. The last of these reliefs was

composed at the time when Sophie Taeuber was drawing a series of vases,

leaves, and metamorphosed sea shells to illustrate my book of poems

Sea Shells and Umbrellas (Muscheln und Schirme): this last

relief is so unusually perfect, its inner brightness is so great, that

I can compare its beauty to nothing less than that of a Greek amphora.

Most of the reliefs of that same period evolve from a circular

background. Earth and sky are intermingled like waves. Dark-green

leaves, deep-blue skies. These works have the solemnity of a wing, the

splendor of a glittering jewel.

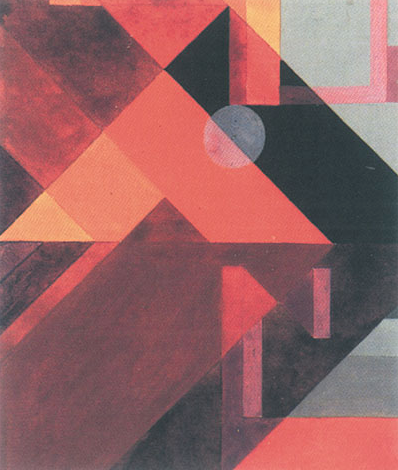

In the years 1932, 1938, and 1939, Sophie Taeuber did four large

compositions in oil, in which she went back to the system of geometric

division of surface that she had used for her water colors in 1916.

She divides the surface into four, six or eight rectangular or square

planes of equal size, sometime uniting two or more of them in a single

flat level organized into smaller ones. Depths take shape and give the

whole a plane spatial reality. These surfaces no longer detach

themselves from the background as in the paintings done in 1933: now

they are two-dimensional spaces in which plane depths open up; surfaces

settle on other surfaces, lean on them, seem to advance toward the

onlooker, sink away, float along lines like flags on their poles.

These are two-dimensional spaces in which lines cut through surfaces,

limit the areas of light and dark, and share the image with one

another. Sophie Taeuber called those paintings Space Paintings.

These plane and spatial realities are created merely by the play of

colors and surfaces without the help of perspective or illusion of volume.

The image always remains flat, and never transgresses the law

dictated by the very nature of objects: the two-dimensionality of any picture.

Sophie Taeuber spent the last two years of her life with me in Grasse,

a town in Southern France. She really loved that area: it was her earthly

paradise. Whenever we went for a stroll, she was radiant with happiness.

She kept urging me on to more and more walks. Her eyes were always

fastened to the silvery-green olive groves, the meditative silhouettes of

the shepherds amid their flocks, the villages jutting up on the mountains,

the flittering, dazzling shield of the ocean. We lived between a well,

a graveyard, an echo, and a bell. A palm tree and some olive trees grew

in our garden. Whenever the palm fronds began to rustle, there was rain.

The olive trees were constantly animated by an almost imperceptible thrill:

each day was brighter and happier than the preceding one, and Sophie equaled

them all.

Her inner clarity struck everyone who met her. She blossomed like a

flower about to droop. The bright inwardness of her being brought

protection and comfort to anyone in suffering. From her purity she

drew the courage and confidence to endure the immense misfortune of

France. Her paintings were filled with glorious brightness. From the

depths of the most intense suffering, blossoming spheres shoot forth.

Depths and heights and rays rise and drop in a vast colored round.

Lost and impassioned, she drew lines, long curves, spirals, circles,

roads that twist through dream and reality. She painted her final

singing circles. In the turret where she had her room, she worked

ardently. Her fine approving profile lowered and rose before the

distant sea. The day before we left Grasse, she meticulously put her

tools in order and carefully stood her paintings against the wall to

let them dry. She was as content as one is after a lovely day.

She was always ready to receive darkness or light calmly. She was

serene, bright, truthful, precise, honest, incorruptible. She opened

life to skies of brightness.