|

Main

|

Role

|

Origins

|

Genres

|

Artists

|

Hogarth

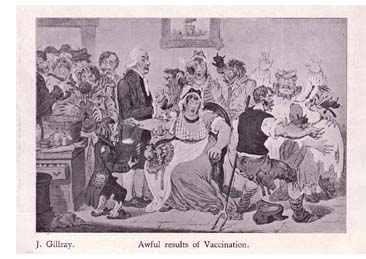

Gillray

Cruikshank

Rowlandson

W

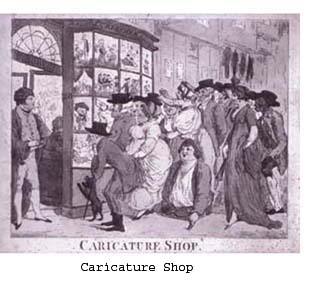

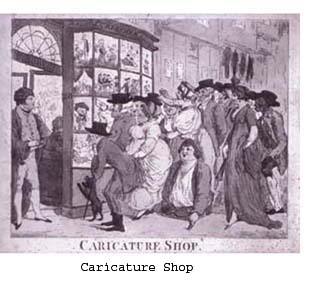

Welcome to The Caricature Shop! This is a site dedicated to satirical art in

eighteenth-century England. This was a watershed time period for

the art form, as it truly began to take shape, both in terms of creativity and popularity.

It was one of the most prominent forms available to express a

biting wit and a desire for social change.

If you’re eager to learn about caricature, and if you're not sure exactly where to start, head to our

role page.

Here, you’ll find out exactly what these satirists were

trying to accomplish with their art and how effective they were in doing so.

If you’re interested in learning about how the art of visual satire was born, check out our

page on its

origins. Here we discuss what led to the creation of the genre and what

forms it borrowed from. A lot of influences go into the birth of any new form of art, and

this one is no exception.

Or, if you’re interested in learning about the different types of satirical art, check out our

genres page. Here you’ll learn about the major targets of eighteenth-century satirists and how

these different targets were attacked. You’ll more than likely be surprised at how

similar the methods were to the ones used by political cartoonists of today.

If you’re still eager for more, head to our

artists page to

learn more about the geniuses of the form. You’ll find out who influenced whom, and

who started what. From Hogarth to Rowlandson, meet the

artists at the forefront of the medium.

Finally, we’d like to say thanks for stopping by and checking out our site.

Enjoy!

Tim and Wes

The Role of Comic Art

The age of enlightenment was a time of profound change for England. The birth of satirical comic art itself

was a testament to the newfound freedom of tongue and pen that the English people enjoyed. That a daring

amateur with a little bit of artistic aptitude and a little bit of keen perceptiveness and biting wit could

mock the most powerful and formidable authorities of the time was unprecedented in England.

Comic art, however, is a broad term. In its loosest sense, it refers to any kind of graphical depiction that

achieves a comic effect. It is not only used as a political critique—often, it is used as a social critique

and as a means to expose the folly and vice of humankind. Often it is used less seriously and is meant purely

as lighthearted entertainment.

Sometimes comic art in eighteenth-century England took the form of caricature—the gross exaggeration of physical

features—to make a statement. Sometimes comic artists used other means, such as pictures within pictures, symbolism,

suggestive juxtapositions, allusions, and even words to ensure that their message was as clear and memorable as

possible. In all cases, comic art was intended to both mock and preach.

In the hands of someone who intended to fight against some aspect of the political or social system, comic art was

a dangerous and effective weapon. Not only could it damage its victim by exposing it in a vicious and merciless light,

it was also able to elicit its own propaganda and, in so doing, convert people to its cause.

As malicious and cruel as satirical comic art may seem to have been, it was not frivolously offensive. Comic art is

meant to depict ourselves in a way that we might not otherwise be able to see with our personal prejudices and biases.

It is meant to reveal parts of ourselves that we do not like to see. It attempts to expose human weakness so that we

might better understand ourselves.

Origins of Comic Art

Though the art of English caricature was a wildly original and inventive one for its time,

it had firm roots traceable as far back as 250 years prior. Like all great artistic and

literary movements, its practitioners took the most relevant pieces and features from

works that had come before them, and melded them to fit its own needs.

The first true caricatures were painted in the early 1500s in Italy by Leonardo da Vinci.

They were born from an attempt on da Vinci’s part to try to personify personality traits as

facial features. The series of works was entitled "The Grotesque Heads." They stand in

striking contrast to the majority of his remembered works, as they do not embrace beauty,

but rather relish in showing uniqueness and flaw in the human form in an exaggerated

manner

(5).

Later, in the seventeenth century, Dutch painters began creating allegorical works

pertaining to all themes and walks of life. These paintings, such as Rembrandt’s "Dead

Peafowl," addressed the various social and political ills of the era. Often subversive in

nature, the works themselves took the shape of everything from still-life paintings to

portraits

(6).

These two forces eventually collided to create English satirical art. Borrowing the

humorously ugly renderings of the Italians and the metaphorical subject matter of the

Dutch, English artists were able to create a kind of art that was both humorous and

meaningful. Though this form was toyed with by various artists throughout the early

eighteenth century, it never really took true shape until

William Hogarth began drawing

satirically in the 1760s.

Hogarth’s advances mixed with the heightened political

awareness in Europe after the French revolution sparked what is often referred to as The

Age of Caricature.

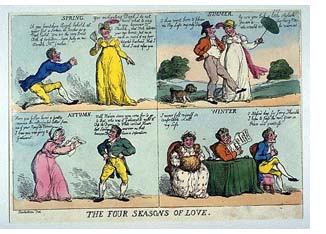

Genres of Comic Art

Though satirical art targeted many common themes, there were two topics that received

the brunt of the attacks more than any others: Politics and Society. Political satire often

tried to defame electoral candidates or expose government hypocrisy. Social satire aimed

instead to point out the crazy idiosyncrasies and hypocrisy of the upper class. Other

themes subjected to visual satire included: literature, art, theater and many others.

Though all of these were very interesting in their own right, and certainly warrant further

attention, none of them had anywhere near the prevalence that politics or society did in

satirical art.

Political

For as long as the concept of government as we know it has existed, so has the propensity

for people to express disdain towards it. Citizens of various countries had been voicing

their opinion on the matter for a long time before with poetry, theater and literature, but it

wasn’t really until the 1700s that caricature truly blossomed as a form of political

criticism.

In the late 1750s, a man named Thomas Townshend began using the techniques

employed by earlier engravers and applying them towards a political model. This gave

Thompson’s cartoons a much greater feeling of propaganda than previous artistic

critiques of the time, as any enemy of Townshend’s was bound to be targeted. His

numerous works, including the pictured “The Recruiting Serjeant,” pulled no punches

(12).

The intense political climate of the period, and often accusatory nature of most political

cartoons forced many artists to use pseudonyms in order to avoid accusations of libel.

Other artists took it a step farther, and left their cartoons completely unsigned, foregoing

any credit they may have received. Political higher-ups were notoriously touchy about

their reputations and were not afraid to make examples of offenders.

Once politicians became aware of the persuasiveness of political cartoons over the

general population, they began using the medium to aim attacks against each other. This

was sparked when John Wilkes began funding prints in the 1760s, which was the first

attempt at using political cartoons as a campaign strategy. At first, the quality of these

cartoons was far inferior to the ones done by those done by freelance artists. However, as

political parties began commissioning more and more talented artists, the quality of these

cartoons increased dramatically

(13). Even the great James Gillray ended up doing

work for both parties over the course of his career. This sparked a war of visuals between

the two dominant parties of the time: the Whigs and Torries.

This over-saturation of politically-biased satire led to somewhat of a backlash in its

effectiveness. At this point in time, many companies began putting out requests for

specifically non-political artwork. The public’s distaste for political satire gradually

faded, and eventually, keen minds began publishing cartoons again, albeit in a less blatant

and offensive manner

(14).

The reaching effects of eighteenth century political satire are nearly immeasurable.

Despite small hiccups here and there, the medium has, if anything, only become stronger

with time. Opening up a copy of USA Today or The New York Times on any given day

of the week will almost certainly result in seeing a cartoon featuring a goofy-looking

rendition of the president or a member of congress making some sort of mistake. This

ubiquity was born in the eighteenth century, and hasn’t shown any signs of going away.

Social

Society’s fascination with wealth and celebrity has been so prevalent for so long that it

borders on a cultural universal. However, this obsession is a Janus-faced one. Along

with their admiration of the wealthy from many, comes a desire to criticize their flaws.

Eighteenth century England was certainly no exception to this rule. Of the myriad topics

criticized by English caricature during this time, none were as frequently targeted as the

wealthy class.

Though its ubiquity in most retrospective volumes leads most to believe otherwise, the

genre did not really take true form until the early 1770s. Throughout the 1700s, class

divisions grew, and the rich got seemingly more and more extravagant. The term “Beau

Monde,” or “Beautiful World” came to be used to describe their lifestyle

(3). As the

distinction between classes became more and more defined, satirical art against the rich

became more prevalent.

An important thing to note about this type of caricature was that it very rarely poked fun

at the concept of earning money. It did not take the rich to task simply for being rich.

Rather, it focused on their follies, eccentricities and bizarre lifestyles

(7). The earning of

money was seen as an honest pursuit that applied to all classes. The rich class’s spending,

however, was poked fun at relentlessly. The caricaturists of the day frequently

questioned why people who had seemingly limitless amounts of money would waste it all

on shiny clothes and obnoxious hairstyles.

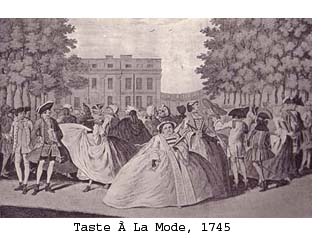

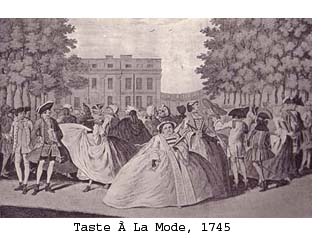

L.P. Boitard’s Taste À La Mode drawings are excellent examples of comic art’s attempt to

make jokes of the eccentric habits of the wealthy. In the series of two drawings, one

subtitled "1735" and the other "1745," Boitard humorously shows

how ridiculous high class fashion of the time had become

(3). In the former drawing, a

group of men and women are shown socializing in a courtyard, dressed nicely but

relatively modestly. In front of them all is a proud soldier. In the latter picture, women

are wearing dresses so big that they can hardly walk, and the men are shown to be

fawning over them. In place of the soldier, stands a particularly short and round woman

who is barely standing up straight due to the extravagance of her clothes. The

commentary on the move from nationalism to individualism, from function to form, is

quite obvious and rather biting.

While this genre of caricature was very broad at first, by the end of the eighteenth century,

it had evolved enough so that it had fewer, but more popular targets to aim its wit at.

These people, mainly rich women like Lady Cecilia Johnstone were truly the celebrities

of the day, and many caricaturists saw it as their as their job to try to take them down a

peg. Celebrity progressively became more and more of an issue

(3). As a result, the

propensity to include famous aristocrats rather than random nameless ones increased.

This allowed for artist’s works to be more well-appreciated and understood by using

recognizable figures to make their point. This allowed for a true melding of man’s

fascination with both wealth and celebrity in a form that would still allow the artists a

valid way to critique society.

Famous Comic Artists

Who was at the forefront of the art form at the time? What made these people so special? What did they do

to make their political statements? How did they advance the form? How did their styles differ? Click on on

image of a comic artist below or use the sidebar to the left to find out more.

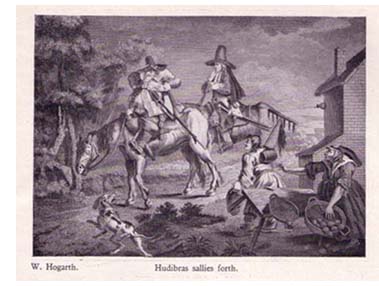

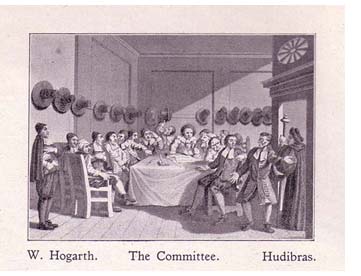

William Hogarth

William Hogarth

William Hogarth once said of his own work: “I have endured to treat my subjects as

a dramatic writer, my picture is my stage, my men and women my players, who by

means of certain actions and gestures are to exhibit a show”

(15). With such an

attitude towards his art, it is understandable that many of the time’s top critics

fallaciously took him for a dramatist, rather than the satirist that he was.

Born in 1697 to a publisher and a shopkeeper, Hogarth was largely self-taught as an

artist. He attempted to study under the famed painter, James Thornhill, but it soon

became apparent that the apprentice was far more skilled than the master

(18).

Hogarth once wrote that he “loved rather to study in the wild academy of nature and

to look in life with which neither lectures nor examples could supply him"

(16).

Early on in his life, Hogarth attempted to make a career in portraiture. He did fairly

well in the field for a short period, but ultimately, his style was far too different from

what was expected of him at the time. The British desired to look beautiful, almost

god-like, in their portraits, and Hogarth’s depictions were decidedly un-flattering. He

strove to create humans who were neither perfect nor wretched. He aimed for

something average, yet unique.

Hogarth soon found himself in a position of mutual affection with his master’s

daughter, Jane Thornhill. Despite the fact that James did not approve of the

relationship, Hogarth and Thornhill eventually eloped. Faced with the challenge of

supporting a wife Hogarth was forced to give up his previous ambitions of becoming

a historical painter. He soon found that there was far more money available in

creating paintings based on the famous theater of the time

(18).

Eventually Hogarth realized that it would be less constricting for him to use his prints

to create his own plays rather than simply interpreting others’ works. He first

achieved notoriety in 1732 with his series of satirical prints entitled “The Harlot’s

Progress,” which ended up being a wild success. These and other works of his were

instrumental in the transforming English caricature from libelous potshots to serious

art form. So groundbreaking was Hogarth’s work, that Biographer T. Clark once said

of of him: “He may be said to have created a new species of painting, which may be

termed the moral comic”

(17).

Hogarth used his instinctive knack for humor to create many other masterpieces,

such as “Mariage a la Mode,” “The Shrimp Girl,” and “A Rake’s Progress.” Like all of

his works, each one of these put his comical talent to use towards some greater

moral purpose. His sense of humor was so prevalent, in fact, that it has often been

said that he could not create a truly serious piece of art if he tried.

Nearly every great English satirical artist who has come since owes something to

Hogarth. From his intriguing moral values, to his sharp sense of humor, to his

wonderful character renderings, his contributions to the genre were innumerable.

One would be hard-pressed to find a more influential caricaturist either before or

since.

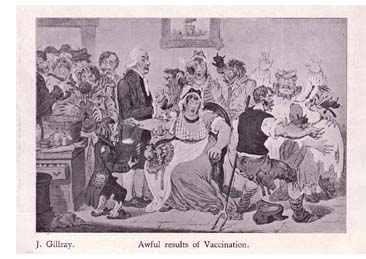

James Gillray

James Gillray

James Gillray, born in London on August 13, 1757, is widely considered to be one of the greatest

cartoonists of eighteenth-century England. He spent three years at the Moravian academy for

boys where he received his only formal education. When the school was forced to close in 1764

as a result of financial troubles, Gillray became apprentice to an engraver, but soon left because the

work was too tedious for him. He joined a group of strolling players, whom he traveled with until

1775. At this time, Gillray returned to London where he began to produce satirical prints

(1).

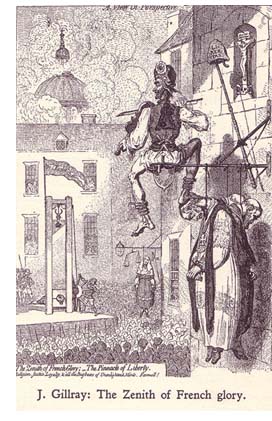

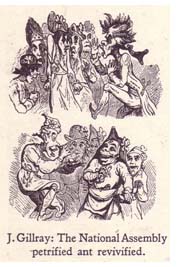

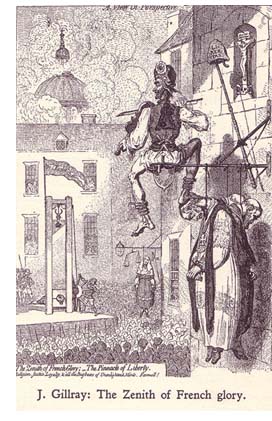

Gillray’s works were characterized by obscenity and monstrous distortion. Much of his art was

offensive in the extreme. He did not try to achieve either beauty or realism in his works. Instead,

the characters of his cartoons were twisted and unshapely. They were often nightmarish and ugly.

He sought to bring out the worst in his victims.

Despite the unattractiveness of his characters, Gillray was a master cartoonist, and, at least from

an artist’s perspective, his work could even be called beautiful. His technique was to combine

etching and engraving to achieve tonal effects. Etching is a technique wherein the etcher "draws

with a needle through a resin surface in a plate, selectively exposing it to an acid bite"

(2). Engraving

consists of using "a sharp tool to incise lines in the plate to hold the heavy printing ink"

(2). To

Gillray, cartooning was as much a science as it was an art.

According to fellow caricaturist

George Cruikshank, Gillray was a “furious etcher,” often

working until his fingers bled

(1). Curiously, Gillray’s passion must have been for the art itself,

because he did not personally seem to hold any strong political opinions himself, despite his

active role in political commentary. He frequently switched sides in political battles without

scruple. As much of an artist as Gillray may seem to have been, he was without integrity, often

submitting to the will of the market. He drew cartoons that he knew would sell. Perhaps his

works did not serve to alter public opinion so much as it served to reflect it.

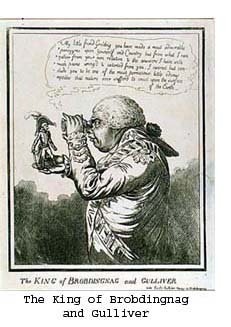

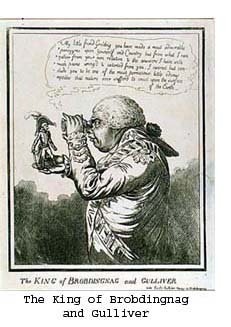

James Gillray lived during the reign of George III during the French Revolution, and one of his

primary targets was Napoleon, whom he nicknamed “Boney.” However, he was not a part of

either the Whig or the Tory party. Although he generally made the French look ridiculous in

comparison to the British, as in, for example, his famous caricature "The King of Brobdingnag

and Gulliver," he also often criticized the British monarchy

(2).

As Gillray aged, he became depressed and lapsed into a state of insanity.

On July of 1811, he attempted suicide but failed. Gillray died on June 1rst,

1815. Many of his unfinished works were completed by

Cruikshank (1).

George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank

Very few eighteenth century comic artists are the subject of as much critical

divide as George Cruikshank. Many art historians make mention of him only

in passing to discuss his mediocrity. Others don’t even feel the need to

mention him at all. His proponents, however, place him on the same

pedestal as other masters of the form, such as

William Hogarth and

James

Gillray (3).

Born in London in 1792, George was the son of Isaac Cruikshank, a mildly

famous political caricaturist. With such lineage, it’s not surprising that he

chose the profession he did; It is said that he learned to draw as soon as he

was able to write

(4). More surprising is the fact that most of George’s

training came from the friend of his family,

James Gillray, rather than his

father himself.

Cruikshank’s critics often single out the box-shaped heads that most of his

characters sported, or the overly flattering waistlines that all of his females

were blessed with as reasons for his feebleness. His line work still falls under

criticism to this day for it’s sketchiness and lack of clarity. Add to this the

fact that most of his drawings were done to a much smaller scale than most

of the others of the time, and the criticisms directed towards Cruikshank

seem almost validated

(3).

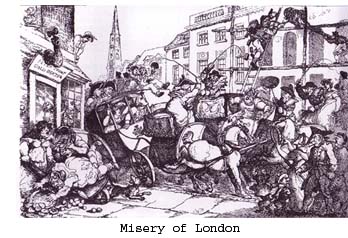

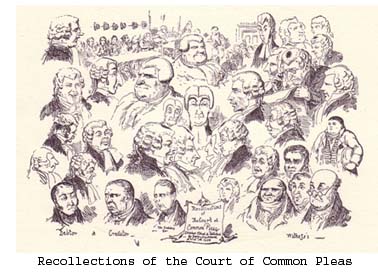

With so many technical aspects stacked against him, why do so many defend

his greatness so fervently? Simply put, his drawings are bursting with life.

Many of his cartoons show off very large crowds of people, and in them,

every single character looks like an individual. Each one’s body language

and facial expression just ooze “character.” While his technical skills may

have been a bit lacking, they were more than made up for by creative vison

and sense of individuality that permeated from his works.

Adding to the divided nature of Cruikshank’s appeal is the penchant he had

for including elements of the supernatural in his art. His inclusion of fairies

and giants in his work is seen by many as mere pandering, but others use it

as a prime example of his range as an artist. His renditions of these

creatures do not look like mere humans endowed with distorted features, but

rather actual giants and faeries

(3).

Despite not being as generally well-remembered as the other great comic

masters of the time, Cruikshank’s art has obtained sort of a cult-like status

within the already small sub-culture of British caricature enthusiasts. While

many of the jokes and commentary within his works do not stand the test of

time as well as the likes of

Gillray’s and

Hogarth’s there is an undeniable

livelihood in his art that must be acknowledged.

Thomas Rowlandson

Thomas Rowlandson

Thomas Rowlandson, born in London, was raised by his wealthy aunt and uncle after his father

went bankrupt. He was able to draw before he could even write. He went to school in Paris and,

afterwards, attended the famous Royal Academy for artists in London. He began his career as a

painter of portraits, but wasn’t able to earn a livelihood at it. As a consequence, he turned to

comic art and was met with phenomenal success

(8).

When his aunt and uncle died, Rowlandson was left with a rich inheritance, but he lost it all

gambling. Fortunately, he was able to reinstate his fortune through his work. Although he was

prone to wasteful excess throughout his life, he was always able to recover himself from the

depths of poverty though his work as a comic artist. While holding up his pen, he would say, “I

have played the fool, but here is my resource”

(8).

Thomas was friends with

James Gillray, but his style could not be any more different. Whereas

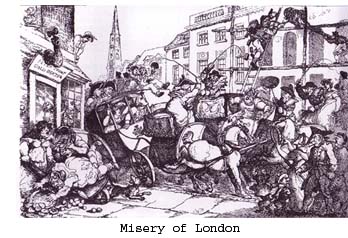

Gillray distorted the targets of his satire while exaggerating certain features, Rowlandson was

far more of a realist. Rowlandson drew reality as he saw it, both in its appearance and its

absurdity. Furthermore, Rowlandson was a much more optimistic artist in comparison to the dark

Gillray. Rowlandson’s drawings were light-hearted and sympathetic. They were free and natural,

and this was reflected in his characters and scenes, which seemed to live and breathe

(9).

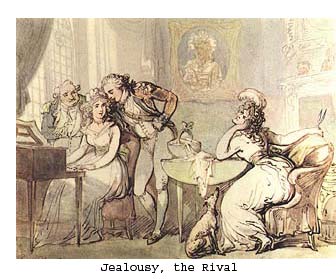

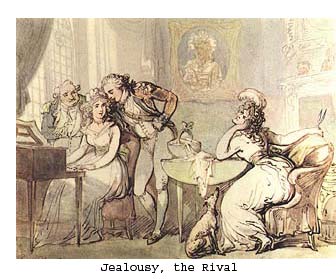

Rowlandson was also different from most satirical artists of his time, such as

Hogarth, because

he did not try to moralize. Often, many of his works were without definite meaning and the

situations he portrayed were simply meant to be admired, mocked, or sympathized with. For

example, in his painting “Jealousy, the Rival,” Rowlandson depicts a simple scene with a young

girl, who sits alone with her dog and despairs as she watches two men shower attention on

another girl

(8).

Rowlandson was mostly a social caricaturist, usually preferring to avoid politics altogether. Like

Gillray, he frequently switched political sides, sometimes almost immediately afterwards

(7).

Rowlandson’s free and easy method of drawing was enhanced by his technique. He was a master

of pen drawing and watercolor

(8). He first drew his outlines with a reed pen, and then he would

cover his images with washes of color

(11). He frequently liked to draw large scenes,

rolling countryside, landscapes, and interiors

(10). Sometimes, he was accused of being a little

too free with his drawings. His critics claimed that he was rough and careless. However, it

cannot be denied that Rowlandson was one of the most naturally gifted artists of his time.

He died in London in April of 1827 after a prolonged illness.

Works Cited

Andersson, Christiane.

Introduction to James Gillray. Bucknell University. 12-7-03.

http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/art/courses/gillray/intro.shtml.

A brief biography on the life of James Gillray. Andersson also comments on the role of comic art in general.

Site contains links to a number of Gillray's works.

Donald, Diana.

The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III. Yale

University Press, 1996.

Donald provides an excellent retrospective on most of the events and movements

concerning eighteenth-century caricature in England. She manages to squeeze in a great

deal of information on very specific topics.

Greig, James.

Comic Art in England. Edward Goldston, 1930.

This book gives excellent descriptions of the big name satirists of the day and goes

into detail about how they affected each other. It also contains a great deal of

information on the trajectory of satire throughout the century.

KMG.

William Hogarth – Biography. Humanities Web. 12-8-03.

http://www.humanitiesweb.org/cgi-bin/human.cgi?s=g&p=c&a=b&ID=99.

This site has an extremely detailed biography on Hogarth. Much of the information

has to do with his life outside of art.

Paston, George.

Social Caricature in the Eighteenth Century. Benjamin Blom, 1968.

This book gives a fine analysis on the many different forms, topics, and genres of

eighteenth-century satire. It also contains plenty of samples of work from many of the most

relevant satirists.

Speel, Bob.

The Home Page of Bob Speel: George Cruikshank (1792-1878). 12-8-03.

http://www.speel.demon.co.uk/artists2/cruik.htm.

Speel’s page is not much to look at it, but it contains rare information on George

Cruikshank, which makes it quite the find.

British Satirical Prints: Hogarth and his Age. 12-8-03.

http://www.bne.es/ingles/agenda/exposicion_hogarth.htm.

This site gives not only a great analysis on the works of Hogarth, but also on the

origins of the art form that predate him and on English satirical art in general.

Childs Gallery: Gillray, James: Biography. Childs Gallery. 12-7-03.

http://www.childsgallery.com/artist_bio.php?artist_id=1468.

This site contains more biographical information on James Gillray.

Handprint: Thomas Rowlandson. Handprint. 12-9-03.

http://www.handprint.com/HP/WCL/artist54.html.

Handprint has some great information on Thomas Rowlandson. His work, life and

influences are all touched on.

Still Life Paintings from the Netherlands. The Cleveland Museum of Art. 12-8-03.

http://www.clevelandart.org/exhibit/stillife/curator.html.

This site has some great information on the Dutch influences of English satirical art.

There are lots of examples as well.

Credits

The Authors

Tim Najmolhoda likes puppies, Christmas, and long walks on the beach with pretty girls.

Wes Bel doesn't like to talk about himself.

The Project

This website was a Fall 2003 project for the esteemed Professor David Porter at the University of Michigan.

Last Updated: Tuesday, 16 December 2003, 3:49 AM EST

Welcome to The Caricature Shop! This is a site dedicated to satirical art in

eighteenth-century England. This was a watershed time period for

the art form, as it truly began to take shape, both in terms of creativity and popularity.

It was one of the most prominent forms available to express a

biting wit and a desire for social change.

Welcome to The Caricature Shop! This is a site dedicated to satirical art in

eighteenth-century England. This was a watershed time period for

the art form, as it truly began to take shape, both in terms of creativity and popularity.

It was one of the most prominent forms available to express a

biting wit and a desire for social change.