|

|

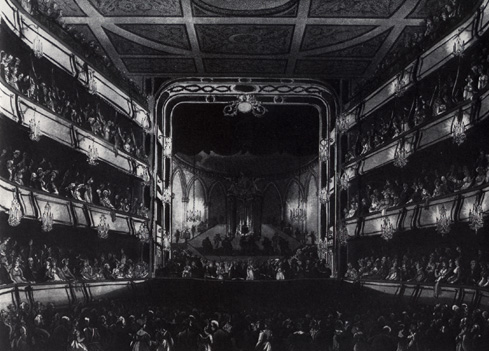

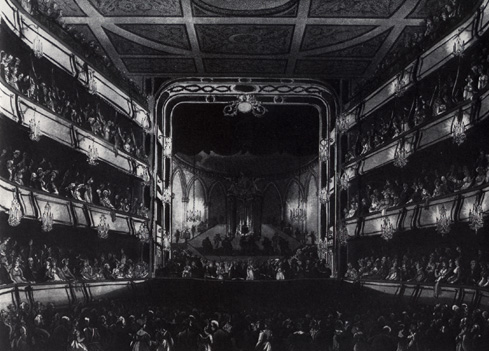

Here we are, at the beautiful Theatre-Royal,

sight of the revival of Aphra Behn's controversial drama, The Rover.

The theater was reopened in December of 1732

by John Rich, who had made a great deal of money off the unexpected

hit, Gay's Beggar’s

Opera, at his other theatre, Lincoln’s Inn Fields.1

This revival began in 1567, nearly a hunderd years after the play was

first performed, and it did not do nearly as well .2

It is surprising that, given the frank sexuality and violent language

of Gay’s immensely popular play, The Rover was rereleased

with an edited, less explicit script. Much of the more sexually suggestive

dialogue was removed in light of the effects of Jeremy Collier’s

Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage.

The revival’s audience was much less enthusiastic than the original

audience ninety years earlier. Scenes of suggested nudity and sexual

language reportedly shocked men and horrified ladies.3

Why was The Beggar’s Opera the success story of the eighteenth

century, while The Rover was edited and censured?

|

|

|

Hellena: Therefore I’m resolved––

Willmore: Oh!

Hellena: To see your face no more––

Willmore: Oh!

Hellena: Till tomorrow.

Willmore: Egad, you frighted me.

– The Rover, III.i.242-48

|

|

Aphra Behn’s Rover

was probably first performed at the Dorset Garden Theatre on March 24th,

1677, where it was extremely popular. Behn originally published the play

anonymously, but after its initial popularity she allowed her name to be

used. The discovery that the author was a woman resulted in a negative critical

response.4 But

even the knowledge that the play was written by a woman does not equal the

intensity of the later audience’s revulsion. |

| Examining the way in which women are portrayed

in these two works gives us a better undersanding of this question. Like

The Beggar’s Opera, The Rover is a play that twists the

roles of sexes, giving women a certain freedom in their sexual identities,

but both plays end with traditional marriages. Still, the slight differences

between the plays are a possible explanation for one’s success and

another’s alteration and poor reception. While Polly Peachum’s

premarital relations with men are celebrated in The Beggar’s Opera,5

her father’s has given his approval, and she is slavishly devoted to

her lover. The high-spirited Hellena chases Willmore against the knowledge

or inclination of her brother, her male authority figure. Her dealings with

Willmore are conflicted, as in this exchange.She does not push Willmore

too far, as she does want him and knows that he is a rover, but she teases

him in a witty, imperial tone that Polly would never take with Macheath.

Polly is thoroughly emeshed in a society where women obey men, while Hellena

marries Willmore, but is certainly not tamed by him. In addition, Hellena

is fighting the prostitute Angellica, for Willmore's love, further complicating

the idea of female purity.6 |

| While the eighteenth century did not respond

to Behn with the same enthusiasm as the seventeenth century, we certainly

hope that you will be of a more enlightened mind and will appreciate the

wit and daring of this exceptional play. |

|

|