|

|

Upon

his death, The New York Times said of Al Capone that he was

"the symbol of a shameful era, the monstrous symptom of

a disease which was eating into the conscience of America. Looking

back on it now, this period of Prohibition in full, ugly flower

seems fantastically incredible. Capone himself was incredible,

the creation of an ugly dream" (Bergreen,

19). As these words suggest, Capone's story seems to provide

a near perfect case study in considering the coming of gangsterhood

into Chicago in the age of Prohibition. His story illuminates

the surrounding issues of immigration and ethnicity, the corruption

of both the government and its law enforcement agencies on the

one hand, and the gangsters, who thrived on bootleg alcohol

sales, racketeering, prostitution, and gambling on the other.

With Capone, these ideas have reached mammoth proportions-he has

been turned by our culture into the symbol of an evil force

thriving through his historical moment of institutional weakness

and confusion. |

Alfonsi Capone came to

America as a young child in 1894 with his family, from Naples, just

one of 42,977 Italians to immigrate that year (Bergreen,

23). His family moved to Brooklyn, which Capone eventually made

his stomping grounds for the beginning of a life in crime. As a

teenager, Capone was recruited by Johnny Torrio, one of the most

successful gangsters on the East Coast, for whom Capone did small

favors and errands. In his early adolescence, Capone contracted

Syphilis, likely from one of a number of the neighborhood prostitutes

he slept with (Bergreen, 45). The

symptoms disappeared a few weeks after the contraction, and Al assumed

the disease had been cured somehow. The disease, however, had merely

gone underground, as is the case with Syphilis, and formed a gradually-increasing

dementia which is likely one of the causes for Capone's frequent

outbursts of violence, for which he became notorious (Bergreen,

85).

Soon after, still a young man,

Al secured a position working Frankie Yale at a bar called the Harvard

Inn. He was involved in a bar fight with another Italian man, whose sister

Al told that she had "a nice ass." The man was furious and sliced

across Al's face three times, giving him the large scars for which he

was nicknamed "Scarface."

|

Frankie

Yale (Bardsley).

|

After

a short stay in Baltimore, Capone moved to Chicago, where Johnny

Torrio had just inherited the throne as crime-king of the city

after his boss, "Big Jim" Colosimo, was murdered by

Frankie Yale in 1920. Torrio offered Al and his brother positions

managing two brothels, and after a year, Al was put in charge

of the Four Deuces, Torrio's head of operations. At the Four

Deuces, it is said, the basement was used to torture men with

information valuable to the Torrio-Capone force, while upstairs

prostitutes offered their services to politicians and mobsters

alike (crimelibrary.com). |

|

After the election of

reformer William Dever to the mayor's office of Chicago, it became

increasingly difficult to run rackets in Chicago, and so the Torrio-Capone

camp decided to move operations to the suburb of Cicero. In Cicero,

Al installed his brothers into positions of power, Frank taking

charge of the local government and Ralph opening a brothel. Al opened

a gambling joint. The Capones eventually gained control of the city,

but his brother Frank was shot and killed by the Chicago Police

Department while he was bullying a number of election workers on Election

Day.

|

Torrio

(Bardsley).

|

|

Dion's

Funeral (Bardsley).

|

Torrio

was eventually tricked into capture during a meeting with another mobster,

Dion O'Banion, at an illegal brewery to purchase stocks in the building.

Torrio went to jail and O'Banion bragged about the deception. O'Banion

was assassinated. With him out of the picture, Capone

took over his bootlegging territory. After an assassination attempt

by O'Banion's men, Torrio went to jail for nine months for bootlegging

due to the O'Banion setup, and afterwards abandoned his life of crime.

Capone inherited the crime arena Torrio built. |

Capone continued to expand

his bootlegging empire. In a word, he met the immense demand for

alcohol (almost all adults drank bootleg alcohol during Prohibition)

with an equally large supply (Bergreen,

529). On a trip to New York to have his son's chronic ear infections

treated with surgery, Capone met with his old accomplice Frankie

Yale to ensure the purchase of a large quantity of Canadian Scotch

whiskey. Throughout the next years, Capone met with increasing pressure

from law enforcement agencies and from outside crime operations. He continued

to expand his empire outside of the realm of bootlegging to

insure that he would have a profit-base if Prohibition was ever rescinded.

The violence reached a peak of epic proportions on Valentine's Day,

1924. Capone and his friend Jack McGurn planned an assassination

attempt on Bugs Moran, who had tried to murder McGurn twice. The

plan seemed to go off without a hitch--Capone's men, dressed as police

officers, lined a group of bootleggers they assumed to contain Moran

against a wall, as if they were conducting a raid. The two "officers"

ran machine guns at the men and led two of Capone's men off the

site as if they were captured bootleggers. Unfortunately, Bugs Moran

wasn't in the group.

After the St. Valentine's

Day massacre, Capone gained unprecedented amount of press hype;

he became a national emblem, a celebrity. The attention of Washington

was gained, and Andrew Mellon, Hoover's Secretary of the Treasury,

conducted an investigation designed to pin income tax evasion and

bootlegging on Capone once and for all. He was eventually arrested

outside a movie theater in Philadelphia for holding a concealed

weapon. He was released from jail early in 1930, and went back later

that year, the investigation having sufficient evidence to convict

him of income tax evasion. They turned away from any more serious

prosecution in large part because they feared the man-- he had placed

a $50,000 ransom on each of the betraying bookkeepers' heads ( see http://members.fortunecity.com/moran9/id59.htm).

He was eventually sentenced to eleven years in prison, which he

served at Alcatraz.

|

Newspaper

article announcing the conviction of Capone (Bardsley).

|

After his release, he stayed at his enormous villa in Palm

Springs, his health continually deteriorating. He died of

a heart attack in 1947 at the age of 48. For

more on Al Capone, including analysis of Capone's contributions

to organized crime, how he changed the city of Chicago, and

how he forever changed organized crime, click

here.

|

|

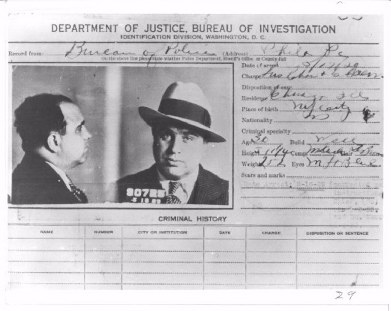

Al Capone

Al Capone