European music, prior to Arab influence which came primarily through involvement in the Crusades, was largely sacred and monophonic in nature. Plainsong chant featured almost exclusively in worship. Gradually, due at least in part to the works of traveling minstrels like troubadours and goliards, instrumental accompaniment, harmony and polyphony would become standards of Western music. The following brief survey foregrounds the troubadours and their heirs with an eye to music history and cultural context.

One of the principle repertories of the Middle Ages, monophonic chant began to be preserved in manuscript form around the 10th century. It consists of unaccompanied melodies set to the Latin texts of the liturgy, principally the psalms, and was used in the Mass. In performance, psalmodic chant may be antiphonal, in which two halves of a choir sing verses in alternation, or responsorial, in which a cantor or soloists alternate with the choir.

Melodies of Gregorian chant, named for St. Gregory the Great (Pope from 590-604) are classified tonally according to a modal system adopted from the Byzantines. Chant, notably, is free in rhythm, as opposed to later mensural music.

Antiphon: a selection from "

In addition to liturgical chant, sequentia or sequence was one of the most important types of music. The form was literary in origin, first consisting of a text added to the Alleluia in the Mass. Structurally, the sequentia always consisted of a melody that was repeated over several hymlike stanzas.

Alleluia: a selection from "

Performed by wandering scholar-poets, but probably writen by learned poets of the period, goliard songs represent an alternative to sacred music during the 12th and 13th centuries in England, France, and Germany. Orff's Carmina Burana (Songs of Beuren) is the most famous, albeit modern, setting of the goliardic songs, exemplifying the goliardic characteristics of profanity, satire, and praise of drink. The text is based on a manuscript discovered in Bavaria in 1803 but written between 1220 and 1250.

Troubadours, more than musicians of any other genre, responded to the Crusades, probably because several directly participated in the fighting. The name troubadour itself may even have been derived from the Arab "tarrab," or minstrel. Jaufre Rudel and Marcabru probably joined the Second Crusade (1147-1149). Of the "about 460 named troubadours (including trobairitz, the women poet-composers) whose poems survive, the music of only 42 are extant" (Aubrey, 6).

Frequently falling under the discipline of literary rather than musical studies, troubadour texts deserve, by their musical nature, to be examined in conjunction with their melodies. Defending the reading of the songs strictly as poetry, Press writes that

...while we know that early mediaeval lyric poetry was, by definition, accompanied by a melody, and while the melodies composed by the troubadours for many of their songs have been conserved in manuscript form, certain partricularities of early mediaeval music notation make the task of reconstruction and reproduction in modern form an extremely problematical one (Press, 4).

But one must remember that many troubadours were professional musicians, and as traveling minstrels, could even be considered portable instruments. The relationships between poetic and musical structure remind us that these were songs, and not simply poems. The difficulty in examining the melodies, as Press points out, is that the songs themselves were highly "unstable:" Van Vleck blames mouvance, which is strikingly evidenced by the near-absence of any singular manuscript of a given song. Mouvance seems the result of multiple transmitters of songs, where each transmitter took some license with the song's text. Transmission occurred through trained performers, but also friends and patrons of the troubadour.

Troubadour songs, it is recognized, lie at the origin of the Western tradition of high lyric poetry. Upholding the ideals of chivalry translated neatly into zeal for the similar ideals fueling the European crusaders, and arguably, the direction of influence was reversible. What troubadours brought back from the fighting, if they returned, was reflected in their songs. The songs themselves often close with an envoi, lines that "send" the song to its audience.

Our concern is with those troubadours most closely connected with the crusades. The earliest extant troubadour texts come from Guilhem de Peiteus (1071-1127). "We know," according to Arnold, "that the Spaniards were imitating Arabian models in rhyme and metre," and suspect accordingly that Europe also borrowed the music that was related to Arabian verse, since the two were inseparable (Arnold, 373).

The chief forms of troubadour songs were the canzo or canzone, which celebrates finÍamor or courtly love, the alba or dawn-song, the sirvente which was a satire, the planh or funereal lamentation, the pastoral narrative pastorela, and various dailogue forms known as tenso or partimen .

A minor nobleman and castellan of Blaye during the second quarter of the 12th century, Jaufre's preoccupation with the "developing cult of vernacular lyric poetry" rivaled his zeal for the ideals of the crusades (Press, 27). His concurrent love-from-afar of the countess of Tripoli would reach a legendary proportion in not only his work, but, owing to his 13th century biographer, also in his life. Nearly exemplifying the notion of courtly love, Jaufre "without ever having seen her, put out to sea, fell ill, and died in the arms of his distant love when first brought to her." (Press, 27) While this account has been considered a confusion of his life with his songs, we can at least confirm the fact of Jaufre's participation in the Crusade of 1148. Credence is added by the fact that no trace of Jaufre exists after 1148, suggesting his death in the Holy Land.

The following poem alludes to this Crusade and is quite possibly a farewell to the cult of courtly love:

When the nightingale in the thicket bestows its love and seeks and takes it, and pours forth its joyful song in joy, and gazes often on its mate, and the streams are clear and the meadows fair, then for the new delight which reigns there, a great joy goes to nestle in my heart.

For one friendship am I longing because I know no richer joy than this: that she should be good to me, if she made me a gift of her love. And she has a well-fleshed body, soft and fair, with nothing which does not befit it, and her love is good and pleasurable.

In this love I am absorbed, waking and then in dreaming sleep, for then I have wondrous joy because I enjoy it, rejoiced in and rejoicing. But her beauty avails me naught since no friend shows me how I might ever have pleasure of it.

For this love I am so eager that when I go running towards her, it seems to me that in retreat I turn from it and that she goes fleeting away; and my horse moves on so slowly that I scarce believe any more that I might reach her, unless she herself is willing to hold back.

Love, gaily I leave you because now I go seeking my highest good; yet by this much was I fortunate that my heart still rejoices for it. But, for all this, because of my Good Protector who wants me and calls me and accepts me, I must needs restrain my longing.

And if anyone stays back here in his delights and does not follow God to Bethlehem, I know not how he might ever be worthy of love or come to salvation; for I know and believe that, to my way of thinking, he whom Jesus teaches is sure of certain doctrine.

The earliest known professional troubadour, Marcabru enjoyed early and sustained patronage of William X (c. 1127-1137). Upon William's death, however, Macabrun wandered in search of patronage and protection, and probably found it from King Alfonso VII of Castile. Alfonso's own participation in the Iberian Reconquista of the late 1130s and early 1140s sparked Marcabru's composition of the songs "Pax in nomine Domini," and "his latest dateable poems allude to the crusade of 1147-1149" (Press, 41). Much of his work criticizes the moral corruption he perceives, "the degeneracy of the nobility, the decline of courtly virtues, and the flourishing of their perverted opposites" (Press, 42). Dejanne No. 5 below is an attempt to formulate his own concept of the courtly ideal.

In courtly manner I wish to begin a poem, if there's anyone to listen to it now. And since I'm thus far committed to it, I'll see if I can make it fine, for now I wish to make pure my song and I'll tell you of many things.

He's indeed capable of acting churlishly who seeks to blame Courtliness, for the wisest and most learned man cannot say or so much pertaininto to it but one could still teach him something, great or small, at some time or another.

He can boast of Courtliness who knows well how to observe Moderation; and if anyone would hear all that there is, or thinks to assimilate all that he sees, then he must needs observe Moderation in all things, or he'll never be courtly.

It is Moderation to speak gently, and Courtliness to love; and may he who would not be despised beware of all vulgarity, of mocking and of acting senselessly. Then he'll be wise, provided he bears this in mind.

For thus can the wise man behave, and the fine lady improve; but as for her who takes two or three of them, and would not keep faith with one, her merit and worth must surely decline, month by month.

Such a love is to be prized which holds itself dearly; and if I say anything crude aobut it through wanting to blame it for some ill, then I approve that it keep me long waiting idly, to have that which it has promised me.

I wish to send this poem and the melody to Sir Jaufre Rudel, over the sea; and I would that the Frenchmen heard it so as to gladden their hearts, for God can grant them this: wherever sin be, may there be mercy.

Also a professional troubadour, his extensive wanderings around Europe, particularly France and Spain, ("where the troubadour lyric found favor") yileded the patronage of Ademar V, viscount of Limoges, a local court. As indicated by his own compositions, he took part in the Third in 1191 in company of the viscount.

Press writes that the seventh poem, finally (Kolsen no. 54), adapted by Giraut from what is thought to be the folk-song of the alba or dawn-song, is generally considered one of the most perfect compositions in the whole corpus of troubadour poetry. The technical skill and the poetic sensitivity with which the conventions of two quite separate literary tradtitions have been combined are immediately perceptible, rendering all comment superfluous. It is indeed a masterpiece by this the "maestre dels troubadours." (127)

Glorious King, true light and splendour, almighty God, Lord, if it please You, to my companion be a faithful aid, for I've seen him not since night came on, and soon it will be dawn.

Sweet friend, if you sleep or wake, sleep you no more; gently rise again for, in the East, I see the star arisen which brings the day, and I have marked it well; and soon it will be dawn.

Sweet friend, in song I call you; sleep you no more, for I hear the bird sing as it goes seeking the daylight through the woods, and I feal least the jealous one assail you; and soon it will be dawn.

Sweet friend, go to the window, and look the stars in the sky! You'll know if I'm your faithful messenger. If you do not, then yours will be the harm; and soon it will be dawn.

Sweet friend, since I left you, I have not slept of got up from my knees, but I've prayed to God, the son of Holy Mary, that He might return you to me in loyal friendship; and soon it will be dawn.

Sweet friend, out there by the steps you begged me that I should not be sleepy but should keep watch all night until the day. Neither my song nor my company pleases you, and soon it will be dawn.

Sweet gentle friend, in such a rich dwelling am I that I would it were never more dawn or day; for the most noble woman that ever was born of mother I hold and embrace; hence I heed not the jealous fool, or the dawn.

Anonymous songs were also highly popular, although most troubadours did take credit for their works. One example of the sirvente genre, in which the poet criticizes the conditions of life and the conventions of society, is the Song of the Crusade. The poet invites Christians to join in a holy war:

I am annoyed, if I dare say so,

by the vile language of gentlemen

and by his fellow-being who wishes to destroy.

It annoys me, as does a horse who draws the reigns,

and I am annoyed by my poor health,

By the adolescent who carries a shield

though without having received a single blow

and by the chaplain and bearded monk,

by the sharp nosed slanderer.

Anonymous "

Simultanously combines several lines or voices of melody, distinct from the monophony featured in plainsong chant. Polyphonic music characterizes, in a wide sense, music of the Middle Ages and Reanaissance, and would arguably come to be perfected by Bach and his contemporaries in the Baroque period. In a narrower sense, polyphony is synonymous wiht canon and fugue forms, and any music featuring counterpoint.

The madrigal is a polyphonic form cultivated in the 14th century in Italy. A rhyming pastoral or amorous text is set for two or three voices, reminiscent of the troubadour canzone.

Josquin Desprez: a selection from

While the role of the Crusades in cultural transmission is undeniable, it ought not to be too naively overestimated. Arguably, the exchanges would have taken place eventually even had they not been the direct result of the wars. Troubadours, however, were obviously influenced by the crusades, in terms of ideals and practice.

Eurpoe's introduction to Arabian music carries, not surprisingly, historical weight that deserves attention. Ancient Greek music, now lost to us, was influenced by if not founded upon the theory and practice fo earlier Semitic music. Just prior to the advent of Islam, the Arab kingdoms' chief influences were Persian and Byzantine in origin, each of these being heirs of the ancient Semites.

Happily, perhaps, for the troubadours, Arabian taste favored vocal music above instrumental -- perhaps as a natural consequence of their esteem for poetry. Unlike most European music of the same time, however, Eastern melodies were often set to modes or scales, and might be mensural, or set to rhythm. But the most notable divergence between Eastern and Western music is perceptible by their corresponding notions of harmony. European sacred music (plainsong or Gregorian chant) shared the unison (each voice sings the same note, possibly in octave), linear (the principle of harmony was founded on succession, not simultaneity) features of Arabian music, although this similarity would dissolve with the development of music in Renaissance Europe. Arnold attributes the development of Renaissance polyphony to Arabian "gloss" or compound, an adornment of melody in which a not is struck simultaneously with its fourth, fifth, or sixth. Incidentally, the minor fifth would be picked up as the most pleasing harmony in the early Renaissance.

Arnold writes that "some sort of musical notation existed from the early years of the ninth century" but that this notation was infrequently employed for pedagogical purposes (361). The "greatest of the benefits which accrued from the Arab contact was undoubtedly the acquisition of mensural music" of which minstrels were the earliest practitioners (374).

"The legacy to western Europe in musical instruments and in instrumental music was of the greatest importance."(Arnold 373) The extent to which troubadour songs were accompanied by instrument, however, can only be surmised. We do have pictorial representations of troubadours holding lutes and various other instruments, but this is the only evidence toward a direct connection in performance.

Brought to Spain and Sicily by the Moors and Saracens, the lute and guitar featured frets which fixed notes on the finger-board. The lute became a favorite of European musicians and was taken north, but prior to Arab contact minstrels used only the harp for accompaniment.

After the 11th or 12th century, when the Arabic qanun reached Europe, the term psaltery commonly referred to this instrument. Its 50 to 100 strings are strung over a shallow trapezoidal box and plucked or strummed. The psaltery fell out of use by the 15th century, but its principle features survive in the zither and dulcimer.

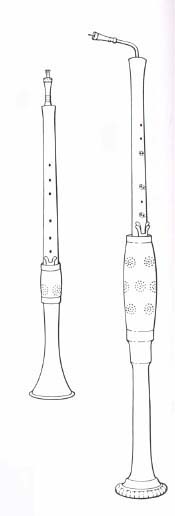

A double-reed woodwind instrument used in Europe from the 13th to 17th centuries, the loud volume the shawm was capable of producing suited it for outdoor use.

Derived from the Arab rabab, the rebec is a bowed instrument, commonly with three gut-strings tuned in fifths.

Last Modified November 18, 1997