In the social production system, as with the commercial system, customers affirm an offering's value, or utility, by way of adoption (e.g., participating in a new recyling offering).

However, social goals often involve two additional (or amplified) demands for new offerings -- a change differential and a customer differential -- representing together a social innovation differential:

i. Change Differential

In addition to adoption, resource leverage may require sustained change in customer behavior and/or capability.

For advances toward social, or collective goals, each of these three types of change -- adoption, behavior, and capability -- may require the change catalysts of an especially high degree of utility and/or of learning:

- Change in transactions (adoption) may require the catalyst of customer learning as a gateway to perceived new utility.

For example, customer learning about landfill facts could catalyze adoption of recycyling services.

- Change in customer behavior (often difficult change) may require the catalyst of an especially high degree of new utility and/or a catalyst of new learning. Behavioral change may involve competing values.

For example, a new conception of home exercise equipment sold commercially could expand customer utility and prompt transactions. However, to advance a social system goal of health, the offering would need to produce change in customer behavior (use of the offering), in addition to adoption, which could require a higher degree of utility and/or learning.

- Change in customer capability typically would require the catalyst of advancing customer learning, or development, in addition to a perception of expanded utility.

For example, teachers could find utility in a new offering for instruction and change their behavior to include its use, but advancing productivity of student learning could require effective use, marked by a sustained change in the teacher-customers' capability, which is likely to require the change catalyst of expanded teacher learning.

In some or many cases, the existing resources that social innovation offerings seek to make more valuable, or productive, are the human-resource customers.

Value that Mobilizes --

Given that it's the very challenge of change in behavior and capability that consumes many of those seeking levers for social advances, the emergent field of positive psychology may offer integral perspective about a level of value held as most influential: "well-being."

First, according to Martin Seligman's theory of well-being, which Seligman calls a "theory of uncoerced choice," free people will seek each of the following five elements of well being (and only these five) "for its sake alone":

- positive emotions (e.g., fun, interest, ease, comfort)

- engagement (of one's signature strengths)

- positive human relations

- meaning (serving something larger than oneself)

- accomplishment (of certain types). [3]

Seligman notes that there is a hierarchy among these most influential elements of value, with positive emotions being lower than the others.

Second, Seligman argues that individual strengths represent the fundamental conduit to the value of well-being:

"The underpinnings of the (five) elements is the (signature) strengths." "(D)eploying your highest strengths leads to more positive emotion, to more meaning, to more accomplishment, and to better relationships." [3-1]

This suggests to me that offerings that call for engaged strengths (including development of strengths) may facilitate efforts to catalyze changes in behavior and capability. This fits with Stephen Goldsmith's ideas in the Power of Social Innovation, where he argues about the importance of "treating individuals as talent assets rather than as victims." It also fits with the premises associated with Jacqueline Novogratz' conception of "venture philanthropy."

Overall, theories like this seem pertinent to social innovation's unusual demands for change.

Offerings vs. Interventions --In the social production system, catalysts for change often are referred to as "interventions." However, even if a change catalyst is addressing a problem situation, the prospect for change may benefit from, or even require, a "positive" incentive.

This fits with comments made by Ashoka founder Bill Drayton regarding his earlier experience with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Drayton spoke to the essential question of ~"How can I make it more attractive to you to [behave in keeping with EPA goals] than to [continue behaviors not in keeping with those goals]?"

Social innovation may represent something like "positive intervention," as a parallel to "positive psychology." Or there may be little more than labeling that is changing.

"[Fill-in-the-blank] Behavior and Education" --From an institutional standpoint, public health's specialized area of "Health Behavior and Education" may serve as a valuable model that has potential counterparts throughout the social production system. For example, there may be benefit to specialized areas such as:

- "Schooling Behavior and Education"

- "Sustainability Behavior and Education"

- "Citizen Behavior and Education"

- and so on.

In fact, there may be benefit to an area labeled "Innovation Behavior and Education," representing offerings that catalyze advances in the behavior and capability for producing innovation.

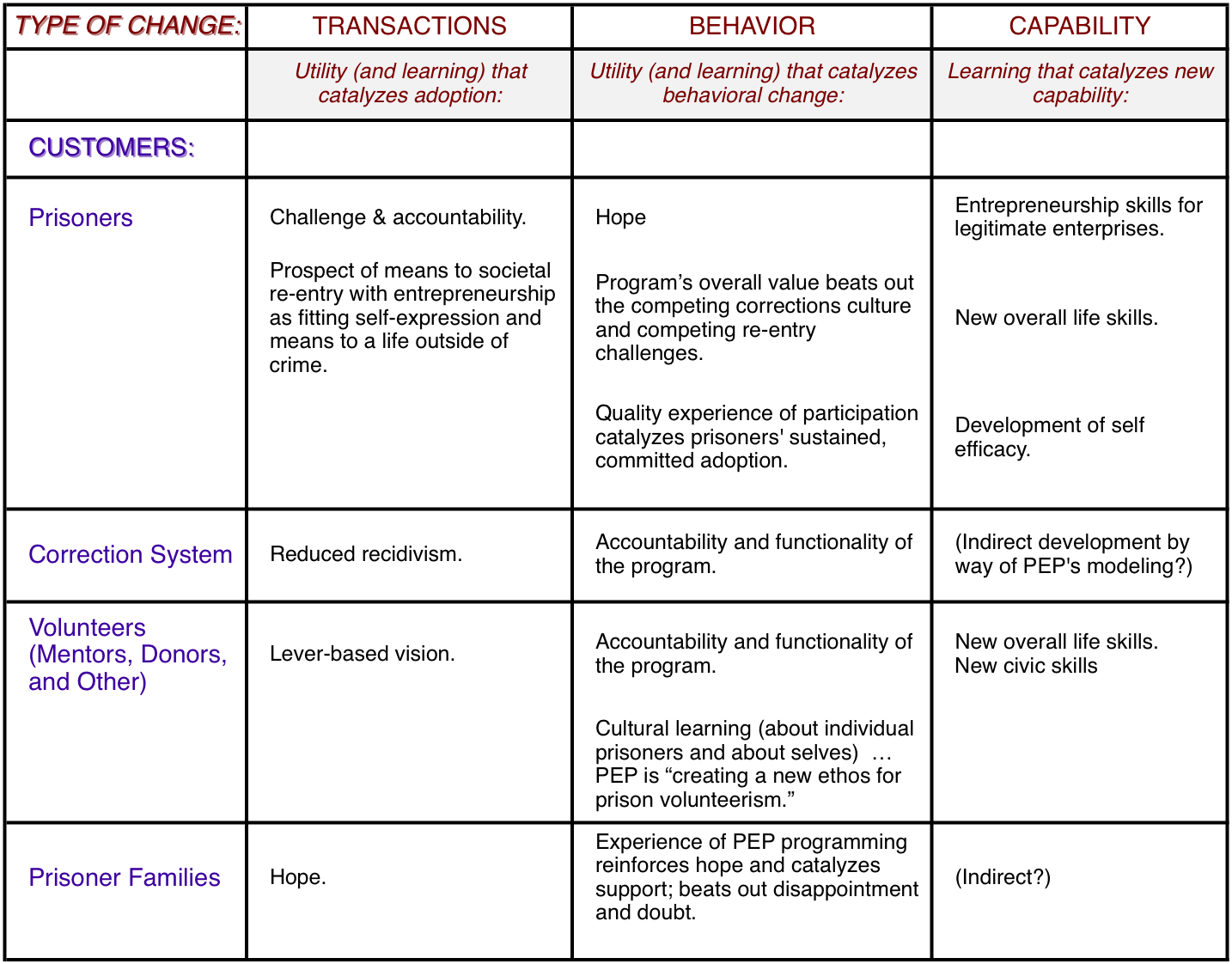

The chart below summarizes the change catalysts pertinent to social innovation's multiple types of change:

Type of Sustained Customer Change: |

|||

Transaction/Adoption |

Behavior |

Capability |

|

Change Catalyst -- |

UTILITY and/or |

UTILITY higher degree |

UTILITY and/or LEARNING |

ii. Customer Differential

The end-user often is not the purchasing (decision-making) customer.

"In a consumer market we make our expectations and demands known with our dollars. ... In social service delivery systems, clients rarely have choice" ... "The power of the market to force new products through old systems -- and the demise of outdated products and services -- does not exist in the social service world" ... "[N]o true market for social innovation exists." [1]

To compensate for this often-missing dynamic of the market:

- An offering intended to represent value to end users may need to catalyze change for multiple customer levels or segments, often within complex systems of social service delivery. This may involve special attention that goes beyond considerations associated with commercial channels of distribution.

For example, initial offerings of food recovery -- intended to advance yield on resources toward the social goal of reduced hunger -- needed to consider fitting catalysts for change among:

- food recipient “end” customers, plus

- customers who have recoverable food to provide (e.g., grocers and restaurants),

- distribution channel customers (e.g., social service agencies),

- funding source customers, and

- volunteer labor customers.

As another example, an offering of instructional improvement intended to advance yield on resources toward a social goal of student learning may need to consider fitting change catalysts among:

- student “end” customers, plus

- teacher customers, and

- additional decision-making customer groups (e.g., school system, parents, and/or taxpayers).

- Other, or additional, means to incorporate decision-making influence from end users may be employed.

For example, involving end users in the co-creation of offerings, with the benefit of mutual learning between customer and provider. (See co-creation within "customer capital," under the heading of innovation's fit with intellectual capital.)

and/or

"(B)uilding a system so low-income families can rate social service programs the way customers rate restaurants on sites like Yelp" ... "If foundations and government agencies began using customer rankings as a criteria when allocating funding to social service programs — that is, if working poor families got to shape the services they needed to get ahead — it would represent a major, and radical, step forward." [2]

iii. Combination as Social Differential

When the distinction of multiple types of change is combined with the distinction of end customers who may not be purchasing customers, the cross-section sketched below can result. The area highlighted in red constitutes often-amplified dimensions of social change, or a fundamental social innovation differential.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Prison Entrepreneurship Program (PEP) provides the offering of entrepreneurship educational programming for inmates. Graduates of the full programming receive the program's commitment of support and resources for life.

The nonprofit organization, founded in 2004, has expanded to recruitment at the 60+ prisons within the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. The organization works in close partnership with the state system.

The resources to be made more productive by way of this offering are the human resource prisoners and the state financial resources associated with corrections.

Throughout the PEP profile, just below, note the offering's fundamental embedding of customer strengths, especially for the prisoners and the mentoring executives:

a. Anchoring hypotheses:Entrepreneurship-based programming that equips inmates with legitimate business skills is a way to tap “into America’s most overlooked talent pool: influential convicted felons.”

In particular, the offering can "incite measurable change" through:

- uniting community CEOs and investors with participating inmates, through shared entrepreneurial passion;

- locating participants within a context of peer support while they remain inmates;

- providing graduates with a lifetime commitment of support and resources.

In addition to prisoners' change, the program can provide the value of meaning to business executive participants (customers), including their own potential self-transformation, which will support sustained commitment and participation.

b. Sample knowledge connected within the above hypotheses draws upon the strands of customer and domain knowledge (corrections and entrepreneurship), with understanding of human and social dynamics incorporated throughout:

The potential:

- "Many inmates come to prison as seasoned entrepreneurs who happened to run illegitimate businesses."

- Some prisoners share essential traits with business executives. They represent "(s)ome of the hungriest entrepreneurs in the country."

The challenge:

- The status quo environment of "(p)rison makes ‘personal change’ difficult."

- "Prison isn’t just an economic drain, but a human one as well."

Particular vulnerabilities:

- "Studies show that former inmates are most vulnerable and impressionable within the first 72 hours following release.”

- Prisoners' families often are the most dubious about prisoners’ potential to change, but also are the most hopeful and a potential source of catalyzing support.

c. Hypothesis Catalyst:

Observation of Corrections System -- "Expecting prison to be a place filled with wild, caged animals, (the PEP founder) was cut to the core to find prisoners who were deeply human—passionate, moldable men thirsty for change. (The PEP founder) immediately recognized their ROI potential. What if she equipped these men with legitimate business skills?"

d. The Prison Entrepreneurship Progam's multiple types of change and change catalysts can be viewed within this table:

[1] Stephen Goldsmith, The Power of Social Innovation, (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2010), pp 134-137

[2] David Bornstein, "Trusting Families to Help Themselves," The New York Times, July 19, 2011

[3] Martin E. P. Seligman, Flourish, A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being, (Free Press, Simon & Schuster: New York, 2011), pp 13-29

[3-1] Seligman, 2011, pp 13-29