Original URL: http://www.reghardware.co.uk/2007/05/28/display_technologies/

Feature Take a look at the back of a typical HDTV, and you'll almost certainly see at the very least one or more Scart connectors; a handful of RCA jacks to feed in stereo audio, composite video and component video; and at least one High-Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI) port...

You might even see a VGA or DVI connector to allow the telly to be hooked up to a PC. In the computer world, we seem to have it easy with these two: VGA for old, analogue displays and DVI for digital connections. DVI was introduced just over eight years ago as VGA's successor, but it has yet to finish it off, despite supporting analog signals as well as digital.

Then there's LVDS, often overlooked because it's hidden away in modern laptops, connecting the LCD to the graphics engine.

What's needed, manufacturers decided, is a single, universal connector to replace all these. In the TV world, that's what HDMI was designed to be: a digital successor to the many different, incompatible analogue connectors that would replace them with a single, compact, cheap and consumer-friendly plug.

![]()

The contenders...

Computers could do with something similar, not only to finally rid them of vestigal analogue connections but also to move to a more user-friendly connector than the bulky screwed-in DVI. It could also be used for both internal displays and external screens. What the PC world needs, in short, is something not so very different from HDMI.

HDMI, however, was designed for HDTV, and computer monitors and graphics cards can now deliver resolutions well in excess of that. But the convergence of these two worlds means more people nowadays want to connect PCs to TVs.

The upshot: three emerging standards are competing for the space on the back of desktops and notebooks used to host the link out to other picture-showing devices: HDMI, Unified Display Interface (UDI) and DisplayPort.

HDMI has been around since late 2002, with updates to the specification following at least annually, and sometimes more rapidly, ever since. The most recent was HDMI 1.3, released almost year ago, and even that's received two minor updates since then.

HDMI: the HDTV favourite

HDMI's raison d'ètre is to channel uncompressed digital video and audio from source to display, along with control data to allow, say, your TV to turn on as soon as you press play on your Blu-ray Disc player. Information flows the other way, to let the TV to tell the player what resolutions it's capable of showing, saving the user having to set it up manually.

And not just pictures: HDMI does sound too. The basic HDMI spec has bandwidth for eight-channel, 192kHz uncompressed audio, along with a variety of compressed audio formats like DTS and Dolby Digital. On the video side, it can handle standard- and high-definition pictures at all the standard resolutions.

The various specification updates have largely added the ability to channel other CE formats - DVD Audio in HDMI 1.1, for example, and Super Audio CD in HDMI 1.2. But version 1.2 began the process of beefing up HDMI's suitability for computers.

Most HDMI-equipped devices on the market currently use HDMI 1.1 or 1.2. However, HDMI 1.3 was a big step forward, boosting the connection's bandwidth to enable it to host much larger screen resolutions than HD TV's maximum 1080p - a crucial move if the connector format's to be used to link even not-so-high-end graphics cards to big monitors. This was a bold statement if intent that HDMI's supporters want the standard to be embraced by the computing world.

DVI's Dual Link mode provides bandwidth-boosting technology to drive screen resolutions of 2560 x 1600 and beyond. Until HDMI 1.3 increased its signalling clock speed from a peak of 165MHz to 340MHz, the CE format couldn't deliver the picture data fast enough to show images of that size. Now it can. That said, the higher-bandwidth mode, dubbed 'Type B' to the original HDMI's 'Type A', has a different connector. An HDMI 1.3 device can support Type A and Type B connectors; an HDMI 1.2 device can only support Type A. But not all HDMI 1.3 equipment has Type B ports.

HDMI also provides for more complex methods of modelling colours. Previous versions allow colours to be represented as 8-bit values in either the RGB (Red, Green, Blue) or YCbCr (luminance, chrominance blue, chrominance red) component colour modes. HDMI 1.3 can also handled 10-, 12- and 16-bit colour radically increasing the number of colours that an image being sent to the display can contain. All this paves the way for better-looking TV pictures, but it's really about delivering higher quality images for folk who really need them: computer-using graphics and video professionals.

Of course, the display needs to be able to display those colours and the source material has to have them there in the first place. Today, 10-bit displays are becoming more commonplace, but HDMI 1.3 has room to cope with these new colour depths as they begin to be used by screens, players and the content itself.

HDMI 1.3 also includes technology to ensure video and audio data remain synchronised which, again, is less of a concern now but may well become so as devices do more processing on the video data to enhance the picture. It may also prove handy when the two come from different locations: a PC's graphics card and its sound card, for instance.

Yet another nod to the PC world: HDMI is fully compatible with DVI technology, though DVI can only deliver digital images not sounds. HDMI supports the HDCP (High-bandwidth Digital Content Protection), which encrypts video data between devices.

HDMI's strength in the consumer electronics world comes not only from its broad industry support, but also because it's mandated both in the US and in Europe for HDTVs. In the US, HDTVs must have HDMI; in Europe they only need HDMI if they're to carry the HD Ready logo, which is near enough the same thing as it's the standard way of indicating to consumers that a display can do HD.

Remember, HDMI isn't essential to pick up an HD signal - the XBox 360 does HD over a component-video connection, for example - but it is necessary if you want to play HDCP-protected content on an HDTV. HDCP isn't widely deployed yet, but that's certain to change in the near future as more consumers buy into Blu-ray Disc, HD DVD and online HD sources.

DisplayPort was originally conceived as a replacement for VGA, DVI and LVDS on PCs - essentially to do for the computer business what HDMI was doing for the consumer electronics world. So, while the ability to support beyond-HD resolutions was always part of the DisplayPort package, sound wasn't, because most PCs handle sound and video separately.

DisplayPort: reaches the computers other ports cannot reach

But just as HDMI has accumulated more PC-focused features, the DisplayPort specification has grown in the direction of consumer electronics, taking on the ability to carry sound data too. DisplayPort was updated to version 1.1 earlier this year, a move which saw the technology incorporate the ability to handle HDCP, though it remains an optional part of the specification, so there's no guarantee a given DisplayPort-equipped device will support it. That may prove a problem for users who want to watch protected HD content on a PC.

DisplayPort does mandate its own copy protection scheme, DPCP (DisplayPort Copy Protection), so vendors keen to support HDCP will have to license both technologies, increasing the cost of implementing the technology.

DisplayPort's rapid development has seen it embrace much the same capabilities as HDMI. It too will support HD and high resolutions like 2560 x 1600, known as WQXGA in the computer graphics world, at a image update rate of 60Hz. It can cope with 8-16 bits per colour component. The addition of sound takes in eight-channel audio, and both sound and video data can be synchronised. Like HDMI, it uses a small, simple connector that's a long way from bulky DVI.

DisplayPort cables can run up to 3m in length, before inevitable signal degradation limits its ability to display beyond-HD resolution data. However, it's capable of pumping 1080p along cables running to 15m.

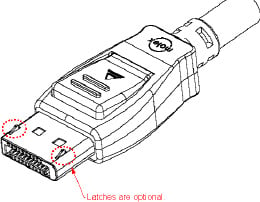

DisplayPort: the business end

Unlike HDMI, DisplayPort isn't compatible with DVI, though it will allow DVI data to be channeled through it. The upshot: while a HDMI-DVI cable is simple to make - just link one of each connector at either end of a cable - DisplayPort-DVI is not. Such adaptors need signal-modifying electronics, so they won't be cheap. Devices capable of sending DVI signals along a DisplayPort cable will be branded Multimode.

The Unified Display Interface (UDI) is, like DisplayPort, intended to be the successor to DVI. It was designed not only to offer superior capabilities than the older connection technology but also be to cheaper and to maintain compatibility with HDMI. So there's no sound support, for example, but it does support higher image resolutions and colour depths than DVI.

Essentially, then, it's 'DVI 2', touted by supporters who, like DisplayPort's backers, appreciate the need for a more advanced, more applicable computer-centric digital display connector but aren't willing to sacrifice backward compatibility to get it.

UDI: source connector (left) and input connector - aka the Sink

A laudable goal, you might think, but one that's as yet to secure serious support. UDI was launched by Apple, Intel, LG, Samsung and National Semiconductor in December 2005. But Intel has since become increasingly pro DisplayPort. Graphics chip makers ATI and Nvidia have contributed work to the development of the UDI spec, but Nvidia is also working with DisplayPort, as did ATI before its merger with AMD. Now that AMD owns ATI, the combined operation has become even more pro DisplayPort, it seems. Samsung appears to be playing the field, supporting HDMI, DisplayPort and UDI.

Three contenders - a three-way battle then? Not quite. HDMI and DisplayPort both now compete as over-arching PC-to-CE display connection specifications, while DisplayPort and UDI are fighting each other to become the de facto successor to DVI. Indeed, UDI's alignment with HDMI might be sufficient to swing the industry behind those two, squeezing out DisplayPort. That may even be reason for UDI's formation: to shore up the HDMI propostion by offering a compatible yet cheap, computer-centric standard that can sit alongside it.

DisplayPort-to-DVI 'active protocol adaptors'

There's certainly little to choose between DisplayPort and HDMI on technology grounds. As both have developed, they've pretty much covered the gaps in their respective feature sets that might have allowed the other format some leverage. Both now incorporate crucial features for consumer electronics applications and for computer roles.

Commentators in the past have looked to licensing costs as a metric for forecasting the outcome of the fight, and while HDMI has seemed pricey, DisplayPort's differences have limited its advantages. Yes, it might be cheaper to license, but allied implementation costs - addition support for HDMI, the ability to work with legacy DVI monitors and so on - mean it could well lose out in the bigger picture. Only UDI can really claim to be cheap, but its limitations means it's unlikely to displace either of the other technologies. Though, as I say, it has the potential to harm DisplayPort's proposition to computer makers.

But UDI is weak when it comes to industry support. HDMI and DisplayPort both have big backers in the PC arena, where support for them is split roughly right down the middle. In the consumer electronics world, however, HDMI is king.

And it's here now, already implemented in HDTVs, next-gen optical disc players, quite a few current-generation set-top boxes and players, and a fair number of PCs and PC-centric graphics cards. No one has yet put a product in stores that incorporates a DisplayPort connector.

And there's the problem: if HDMI does what DisplayPort does, and it's readily available for licensing and implementation now, why pick an alternative that isn't? In many cases, it's politics - vendors are making choices based on decisions already made by their competitors. Others are backing all two or three of the formats so they're covered no matter which connector comes out on top.

HDMI is certainly going to continue to find a home in notebooks and small form-factor desktop systems with an eye on the living room, since HDMI will quickly become the way to connect a PC to a TV.

DisplayPort's strength is its PC-centricity, allowing it to be positioned as a 'serious' alternative to the frivolous home entertainment stuff HDMI connects you to. It's not hard to imagine a world, a few years hence, where computers connect to TVs via HDMI and monitors via DisplayPort or UDI. Think of all the new kit big business buys. If you're fitting an office out with 100 PCs and 100 screens to go with them, you're not going to waste too much time pondering how the two components will be connected together.

Furture laptops will have DisplayPort or UDI to simplify the connection to the LCD, and if DisplayPort's already on board, why add HDMI? Because some folk will want to connect their notebooks to TVs. Again, if you're going to have two connectors, why not opt for cheapest approach: UDI for PC connectivity, HDMI for CE links? Assuming UDI doesn't just fade away for lack of support, of course...

What we have then is a re-run of the old USB vs Firewire debate: two standards that do, give or take a plus point or two, the same job largely as well as each other. In each case, sufficiently large industry camps have formed around each to ensure neither will vanish, and vested intellectual property and licensing interests means there's little chance of the two coming together into a single standard. ![]()

Screen stars: Ten HDTVs on test (18 May 2007)

http://www.reghardware.co.uk/2007/05/18/group_test_tvs/

HD TV in the UK (8 December 2006)

http://www.reghardware.co.uk/2006/12/08/hd_tv_uk_guide_updated/

© Copyright 2007