Agriculture Street Landfill

Environmental Justice Case Study

by Alicia Lyttle

December 2000 (Updated January 2003)

|

Table of Contents |

| References |

|

PROBLEM

The History of a Landfill

Timeline of Events

1948-1958 The dump is converted and used as a sanitary landfill.

1958-1959 The landfill is closed.

1965- The landfill is reopened to receive debris created by Hurricane Betsy; open burning of waste continued for 6 to 7 months, after which the area was covered with ash from city incinerators and compacted with bulldozers.

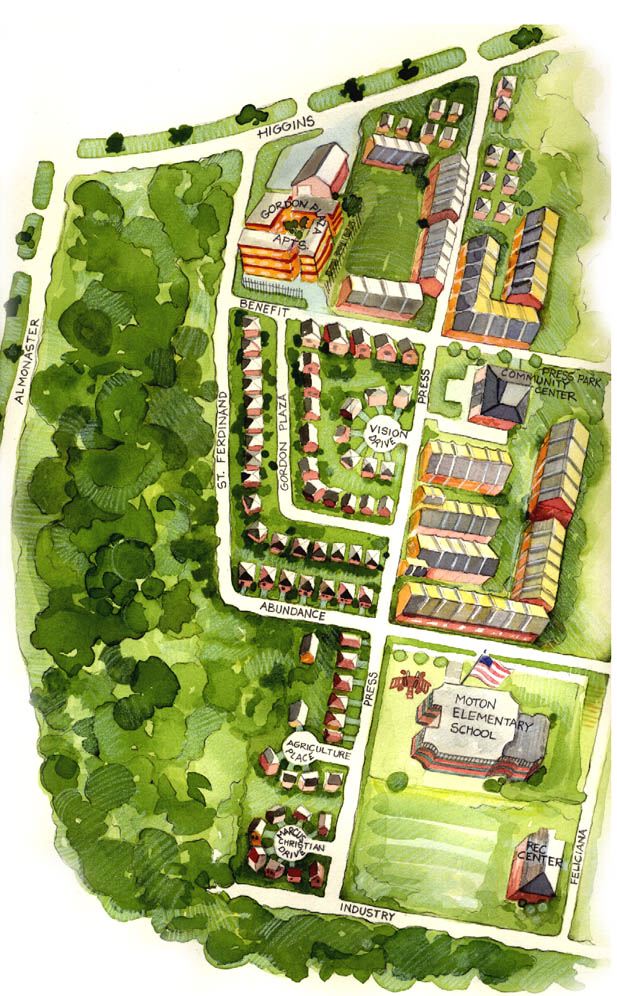

1976-1986 The northern portion of the site was redeveloped to support housing (390 properties are on the site of the old landfill), small businesses, and the Morton Elementary School. The residential properties received a relatively thin (often 6 inches or less) covering of soil; the Moton school was built upon a few feet of clean soil.

1986 The EPA completed a site investigation. Under the “old” Hazardous Ranking System, which excluded ingestion, the site did not qualify for placement on the National Priorities List (NPL).

1993 On May 4, community leaders from the Moton Elementary School area filed complaint with the Gulf Coast Tenants Organization and requested EPA to re-evaluate the site. In September, the EPA collected additional samples for use in the revised HRS model (that reflects ingestion and a soil pathway).

1994 The EPA initiated an accelerated remedial investigation integrated with removal actions. Fieldwork was completed in May 1994, including the erection of a fence around the undeveloped area and removal of highly contaminated soils at children’s play area. The site was proposed to the NPL on August 23, 1994. Due to community concerns created by Superfund listing, the school board announced on August 24 that the Moton School would not open and that students would be bussed to a different school. The site was formerly added to the NPL on December 16,1994.

April 27, 2001 EPA completes cleanup project. 99% of the site

has the first two feet of soil replaced. The remaining 1% of the site belongs

to nine private homeowners in the community who elected not to participate

in the removal action. (EPA

Agriculture Street

Home Page)

A Dirty Political Deal

A program was implemented that targeted low-income African-American families for a piece of the American dream, the opportunity to own their own home. The Mayor at the time, Dutch Morial, and other city leaders billed this development as a way for low to middle income African-Americans to have a piece of the American Dream. It attracted African-Americans who were told that this would be the “new wave of power in New Orleans’ black community.” Proud resident began moving in, completely unaware that they were laying their foundations on a dump (Timmons-Roberts, 2000).

Cheated out of the American Dream

Only shortly after the homes were sold, residents, excited about starting a new

life in their first home in this new community, headed to their lawns and gardens

to plants flowers and produce. After

digging only a few inches residents noticed something was unusual as they found

glass in the soil, and a few started to find car parts and trash.

When one resident tried to put a fence in her yard the fencing company

quit the job as their drill bit kept tearing up on what they felt was a car

buried in the backyard. After a few

years of living in the community residents grew concerned about the high rate

of cancers and someone at City Hall mentioned to resident Elodia Blanco that

she was living on an old city dump. Residents immediately began to organize and after expressing

their concerns, the EPA came into the community to perform soil sample tests.

Tests on the soil were conducted and 150 contaminants, 50 of which are

carcinogens, (cancer causing chemicals) were found in the soil.

Among the toxic substances found were arsenic, lead, mercury, barium,

and other organic compounds that are associated with pesticides and the burning

of waste.

Residents of the neighborhood built on the former Agriculture

Street Landfill in New Orleans meet for a weekly update on the

progress of their environmental justice battle.

Staff photo by Thom Scott/The Times-Picayune

The problem here is that these people were cheated,

not just out of the American Dream but cheated of the right to a clean safe

environment in which to raise their families.

A Clean-Up or a Cover-Up?

In 1997 the EPA decided on a remedial plan, which was to remove 2 feet of soil

from the area surrounding residents homes.

After the soil is removed a plastic liner and a mesh liner is placed

down and clean soil (sand) is placed on top of it.

It is estimated that this clean-up plan, after completed will only clean

up 10 percent of the site. Homes, sidewalks, driveways, roads and other

obstructions cover the other 90 percent. So,

only soil that is directly exposed will be cleaned up as the EPA predicts that

it is unlikely that the “clean” soil will be re-contaminated by the surrounding

“dirty” soil regardless of the sites’ low elevation and high water table.

EPA

contractor cleaning up the undeveloped land at the site.

Photo by Alicia Lyttle

The request of the people here is simple.

They want to be moved out and given a chance to live on clean and solid

ground. The problem is that relocation costs are estimated to be at $12

million dollars. But, as mentioned

earlier this site is on the EPA’s National Priorities list and the Superfund

site is being cleaned up. So, is it

cheaper for the government to clean up the site than to relocate residents?

The answer is a resounding NO. In

fact it has cost the EPA over $20 million dollars to clean up the site (as

of 12/02/00) and the site is still under ‘clean-up.’

It costs almost twice of what it would have cost to move the residents

out. The EPA justifies this a few different ways. First, the EPA claims that the money is not

allocated for relocation and can be used solely for cleanup and that it would

literally take an act of Congress to clean up the site. The Congressional representative for the community,

Congressman William Jefferson, has tried but failed in every effort to attain

Congressional allocation of funds for relocation. The EPA also puts responsibility of relocation

on the City, who claims to be too poor to take on such an endeavor.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), who loaned

and granted the money to build the homes on the landfill, shifts the blame

to all of the other agencies.

The “Clean Up”

KEY

ACTORS

Concerned

Citizens of Agriculture Street Landfill: Community

group fighting for relocation off of the Agriculture Street

DCHC:

Desire Community Housing Corporation: Contractors who built on the Agriculture Street

Landfill Site.

Greenpeace: An Environmental Organization

that assisted the community in New Orleans and arranged for a community

Grover

Hankins; Thurgood Marshall School of Law: Attorney who assisted the Concerned Citizens of Agriculture

Street

Mayor

Dutch Morial: The Mayor of the City of

New Orleans when the Agriculture Street Landfill site was proposed as a

Mayor

Mark Morial: Son of the former Mayor Dutch Morial. Mark Morial was Mayor of the City of New

Peggy

Grandpre:

President of Concerned Citizens of Agriculture Street Landfill.

http://gladstone.woregon.edu/~caer/peggy-grandpre.html

Sierra

Club:

Environmental Organization that assisted the Concerned Citizens of Agriculture

Street Landfill. www.sierraclub.org

Tulane

Environmental Law Clinic: Law Clinic that assisted the community in their struggle and accompanied

them to

United

States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): The

government agency responsible for cleaning up the site. www.epa.gov

Many

others played a role in this battle…

DEMOGRAPHICS

Site Description (EPA Publication,

1999)

Location: The site in located in the city of New Orleans, Louisiana.

It is approximately three miles south of Lake Pontchartrain and about

3 miles north-northeast of the Vieux Caree and the Central Business District. The approximate

Population: The 1990 Census identifies 390 residential units (some 1,000 people)

on the site. The community is

Settings: The 95 acre former city disposal area that has been partially

redeveloped. 47 acres of the site

have private

STRATEGIES

As part of the environmental justice movement this community has brought the issues of “contaminated communities” to the forefront of the movement. Their struggle took them to City Hall, to their Senators’ offices and to meet with their Congressman William Jefferson. They traveled to Washington D.C., to meet with their representatives and with HUD, with the EPA and with members of Congress concerned about environmental justice. Elodia Blanco traveled as the neighborhood’s representative to Geneva Switzerland to testify at the United Nations (U.N.) Commission on Human Rights. This community will continue to fight for their right to a clean and safe environment.

Community meetings

The

Agriculture Street Landfill community holds community meeting every Wednesday

night at 7 p.m. in the front yard or

Networking

This

community networked with small groups as well as large national organizations

such as Greenpeace and CHEJ (Citizens

Legal Support

The

community has received various forms of legal support from the Thurgood Marshall

School of Law, the Earthjustice Legal

Staff photo by Thom Scott/The Times-Picayune

Residents of the Agriculture Street Landfill neighborhood

in New Orleans protest in front of the White House. Residents'

homes are built on top of soil found to contain 149 toxins,

44 of which are cancer causing.

SOLUTIONS

“We

think the only solution to this problem is for the community to be relocated

and we believe that this will happen in the

RECOMMENDATIONS

Because

of residents’ fears that the cleanup was extremely superficial they have not

given up and will continue to fight for

KEY CONTACTS

Peggy

Grandpre

President

Concerned

Citizens of Agriculture Street Landfill

Rebecca

Dayries

Community

Outreach Coordinator

Tulane

Environmental Law Clinic

(504)

865-5787

Alicia

Lyttle

Former

volunteer with the community

Coalition

Against Environmental Racism, Bio of Peggy W. Grandpre,

http://gladstone.uoregon.edu/~caer/home.html

Daugherty, Christi. (1998) “Digging In.” The Gambit (New Orleans). November 3

Dayries, Rebecca. (December, 5, 2000) Interview. Community Outreach

Coordinator. Tulane Environmental Law

Clinic.

ECO-USA.Net,

"Louisiana Waste Sites"

http://www.eco-usa.net/sites/la.html

EPA

Region 6 Agriculture Street Home Page.

http://www.epa.gov/earth1r6/6sf/sfsites/Default.htm

EPA Publication. (October 4, 1999) Agriculture Street Landfill, Louisiana EPA ID # LAD981056997.

Environmental Protection Agency. n.d. “Record of

Decision (ROD) Abstracts: Agriculture Street Landfill.”

http://www.epa.gov/oerrpage/superfund/sites/rodsites/ 0600646.htm. Accessed 7-27-99. EPA Record

of Decision.

ENVIROSENSE, EPA, Air Enforcement Division, National Enforcement

Highlights

http://es.epa.gov/oeca/ore/aed/abus/prrts/nat.html

Grandpre, Peggy. (December 3, 2000) Interview. President Concerned

Citizens of Agriculture Street Landfill.

Grandpre,

Peggy. (2000 – to be published) Evaluations of health hazards in communities

exposed to environmental toxicant.

Environmental health problems –A communities perspective.

Knight,

Danielle. (April 4, 1999) "USA: Environmental Justice Delegation

Heads to UN Commission" Corporate Watch.

http://www.corpwatch.org/trac/corner/worldnews/other/368.html

Leiker,

Amanda. Environmental Racism and Women

in Louisiana, The Pier Glass.

Leiker,

Amanda. Agriculture Street. Unpublished paper.

Motavalli,

Jim. (July-August 1998) "Polluters That Dump on Communities of Color Are Finally

Being Brought to Justice"

E-Magazine Toxic Targets

National

Council of Churches. (1998) NCC News Archives, African American Church Leaders

Pledge Their Support to the Struggle Against Environmental Racism.

National

Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS)Worker Education and Training

Program: Proceedings of the Spring Awardee Meeting And Superfund Job Training

Initiative Meeting. (April 19-20, 1999).

http://204.177.120.20/wetp/clear/resource/99vttechandaward/report/99awardee_sjti_finalreport.htm

New Orleans City Planning

Commission, (1999) Land Use Plan "Planning District Seven "

Schleifstein,

Mark. (July 10, 1999) “Ag Street residents livid over EPA ruling.” New Orleans Times-Picayune.

Sierra

Club, Agriculture Street Landfill Site, http://www.sierraclub.org/toxics/resources/agstreet.asp

Timmons

Roberts, J. ; Melissa Toffolon-Weiss, (Latest edits: August 11, 2000. 3pm)

"CHRONICLES FROM THE ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE FRONTLINE" MS. SUBMITTED TO CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS (an unpublished book)

US

Army Corps of Engineers, New Orleans District, Agriculture Street Landfill

Superfund Site New Orleans, Louisiana

http://www.mvn.usace.army.mil/pd/iis/agriculture.htm

Warner,

Coleman. (September 13, 2000) “Residents relent on cleanup, Homeowners seek

to avoid loan snags.” The Times

Picayune (New Orleans).