The Narmada Valley Dam Projects

|

Table

of Contents |

|

Problem

www.sierraclub.org/human%2Drights/india/index.asp

“For over a century we’ve believed that Big Dams would deliver the people of India from hunger and poverty.

The opposite

has happened.”

The Narmada Valley Development

Project is the single largest river development scheme in India. It is one of the largest hydroelectric

projects in the world and will displace approximately 1.5 million people from their

land in three states (Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh). The environmental costs of such a project,

which involves the construction of more than 3,000 large and small dams, are

immense. The project will devastate

human lives and biodiversity by inundating thousands of acres of forests and

agricultural land. “The State” (India)

wants to build these dams on the Narmada River in the name of National

Development. But “How can you measure progress

if you don’t know what it costs and who has paid for it?” (Roy 16).

Each monsoon season thousands of

people are told by the Indian government that they will have to be relocated as

their ancestral lands are flooded out.

“The people whose lives were going to be devastated were neither

informed nor consulted nor heard” (Roy 26).

A disproportionate number of those being displaced are tribal people:

Adivasis and Dalits.

Damming the Narmada River will

degrade the fertile agricultural soils due to continuous irrigation (rather the

seasonal irrigation which is dependent on the monsoon), and salinization,

making the soil toxic to many plant species.

The largest of the dams under construction is the Sardar Sarovar, which,

if completed, will flood more than 37,000 hectares of forest and agricultural

land, displacing more than half a million people and destroying some of India’s

most fertile land.

The thing about multipurpose dams

like the Sardar Sarovar is that their “purposes” (irrigation, power production,

and flood control) conflict with one another.

Irrigation uses up the water you need to produce power. Flood control requires you to keep the

reservoir empty during the monsoon months to deal with an anticipated surfeit

of water. And if there’s no surfeit,

you’re left with an empty dam. And this

defeats the purpose of irrigation, which is to store the monsoon water (Roy

34).

In the end, the Big Dam will produce only 3% of the power

planners say it will – that’s only 50 megawatts! Additionally, when you take into account the power needed to pump

water through the network of canals inevitably attached to the dam, the Sardar

Sarovar Project (SSP) will consume more electricity than it produces! Another problem with the SSP is that its

reservoir displaces people in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, but its benefits

go to Gujarat (Roy 34-35). Even though

the arid regions of that state, Kutch and Saurashtra, are not mentioned in the

water-sharing award as recipients of drinking water.

The proposed dams will affect

millions of people but only a certain percentage of them will be privy to the

government’s resettlement and rehabilitation (R & R) programs. The problem here arises in defining who are

Project-Affected Persons (PAPs). The

World Commission on Dams urges that the “impact assessment includes all people

in the reservoir, upstream, downstream and in catchment areas whose properties,

livelihoods and nonmaterial resources are affected. It also includes those affected by dam-related infrastructure

such as canals, transmission lines and resettlement developments” (www.irn.org/wcd/narmada.shtml). In reality, however, people affected by the

extensive canal system are not considered as PAPs. These people are subject to R & R packages, but not the same

ones as those living in the reservoir area.

Unbelievably, those not entitled to any compensation at all are the

hundreds of thousands whose lands or livelihoods are affected by either

project-related developments or downstream impacts.

Background

“Big Dams

are to a nation’s ‘development’ what nuclear bombs are to its military arsenal.

They’re both weapons of mass destruction.”

-

Arundhati Roy

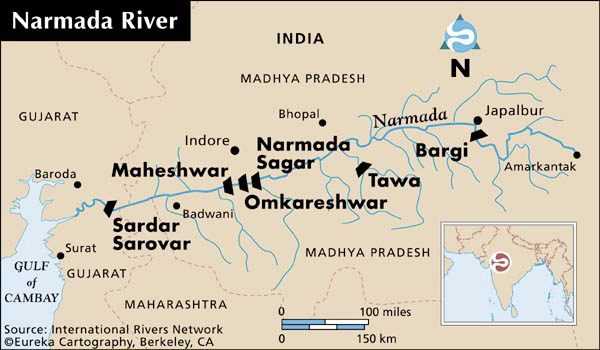

The Narmada River, on which the Indian government

plans to build some 3,200 dams, flows through three states: Madhya Pradesh,

Maharashtra, and Gujarat. Ninety

percent of the river flows through Madhya Pradesh; it skirts the northern

border of Maharashtra, then flows through Gujarat for about 180 kilometers

before emptying into the Arabian Sea at Bharuch.

Plans for damming the river at Gora in Gujarat

surfaced as early as 1946. In fact,

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru laid the foundation for a 49.8-meter-high dam

in 1961. After studying the new maps

the dam planners decided that a much larger dam would be more profitable. The only problem was hammering out an

agreement with neighboring states (Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra). In 1969, after years of negotiations

attempting to agree on a feasible water-sharing formula, the Indian government

established the Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal. Ten years later, it announced its award. “The Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal Award

states that land should be made available to the oustees at least one year in

advance before submergence” (www.narmada.org/sardarsarovar.html).

Before the Ministry of the Environment even cleared

the Narmada Valley Development Projects in 1987, the World Bank sanctioned a

loan for $450 million for the largest dam, the Sardar Sarovar, in 1985. In actuality, construction on the Sardar

Sarovar dam site had continued sporadically since 1961, but began in earnest in

1988. Questions arose concerning the

promises about resettlement and rehabilitation programs set up by the

government, so by 1986 each state had a people’s organization that addressed

these concerns. Soon, these groups came

together to form the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA), or, the Save the Narmada

Movement.

In 1988, the NBA formally called for all work on the

Narmada Valley Development Projects to be stopped. In September 1989, more than 50,000 people gathered in the valley

from all over India to pledge to fight “destructive development.” A year later thousands of villagers walked

and boated to a small town in Madhya Pradesh to reiterate their pledge to drown

rather than agree to move from their homes.

Under intense pressure, the World Bank was forced to create an

independent review committee, the Morse Commission, which published the Morse Report

(a.k.a. Independent Review) in 1992.

The report “endorsed all the main concerns raised by the Andolan [NBA]”

(www.narmada.org/sardarsarovar.html). In author Arundhati Roy’s opinion “It is the

most balanced, unbiased, yet damning indictment of the relationship between the

Indian State and the World Bank.” Two

months later, the Bank sent out the Pamela Cox Committee. It suggested exactly what the Morse Report

advised against: “a sort of patchwork remedy to try and salvage the operation”

(Roy 45-46). Eventually, due to the

international uproar created by the Report, the Bank withdrew from the Sardar

Sarovar Project. In response, the

Gujarati government decided to raise $200 million and push ahead with the

project.

While the Independent Review was

being written and also after it was published confrontations between villagers

and authorities continued in the valley.

After continued protests by the NBA the government charged yet another

committee, the Five Member Group (FMG), to review the SSP. The FMG’s report endorsed the Morse Report’s

concerns but it made no difference.

Following a writ petition by the NBA in 1994 calling for a comprehensive

review of the project, the Supreme Court of India stopped construction of the

Sardar Sarovar dam in 1995. Tension in

the area dissipated but soon the NBA’s attention shifted to two other Big Dams

in Madhya Pradesh – the Narmada Sagar and the Maheshwar. Though these dams were nowhere near their

projected heights their impacts on the environment and the people of the valley

were already apparent. The government’s

resettlement program for the displaced natives “continues to be one of

callousness and broken promises” (Roy 51).

In 1999, however, the Supreme Court allowed for the dam’s height to be

raised to 88 meters (from 80 meters when building was halted in 1995). In October 2000, the Supreme Court issued a

judgement to allow immediate construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam to 90

meters. In addition, it allowed for the

dam to be built up to its originally planned height of 138 meters. These decrees have “come from the Court

despite major unresolved issues on resettlement, the environment, and the

project’s costs and benefits” (www.narmada.org/sardarsarovar.html).

“Nobody builds Big Dams to

provide drinking water to rural people.

Nobody can afford to.”

-

Arundhati Roy

Native people

Dalits are the “Untouchables” of

the caste system. Translated literally

the Dalits are the “oppressed” or “ground-down.”

Adivasi is the term used to

designate the original inhabitants (indigenous people) of a region.

The State

The government of India supports

the building of over 3,000 dams on the Narmada River. What the State fails to take into account are the infinite costs

of what it terms National Development; the millions of lives affected by the

devastating environmental impacts of building dams.

Narmada Bachao

Andolan, The Save the Narmada Movement

The NBA is a people’s movement

formed from local people’s movements in Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and

Gujarat. Through peaceful means, the

NBA has brought much media attention to the plight of the native people along

the river. Medha Patkar is a prominent

leader of the group.

World Bank

The World Bank had originally

supported the Sardar Sarovar with a $450 million loan. However, after appointing an independent

panel to review the impacts of the project the Bank withdrew support. The panel expressed much concern that the

environmental and social impacts of the project had not been properly

considered.

The Supreme Court

The Court is one of the most

formidable opponents of the NBA. It has

exercised its power over the people through judgements to continue with

building of dams along the river, disregarding concerns about the dams’

environmental and social impacts.

“Every aspect of the project

is approached in this almost playful manner,

Even when it concerns the lives

and futures of vast numbers of people.”

In a country where 200 million people (one-fifth of

the population) do not have safe drinking water, 600 million (two-thirds of the

population) lack basic sanitation, and 350 million (two-fifths of the

population) live below the poverty line, it is no wonder that the government of

India wants to implement projects that could potentially improve the lives of

the people. Unfortunately, the State

chose a method that has and will likely cause more harm than good. According to the government, the Narmada

Valley Dam Projects will provide water to 20 to 40 million people, irrigate 1.8

to 1.9 million hectares of land, and produce 1450 megawatts of power. The Narmada Bachao Andolan and other

organizations believe otherwise. They

believe these claims are greatly exaggerated.

These groups estimate 1.5 million people (about 10,000 families) will be

displaced in the three states of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Gujarat.

A disproportionate number of oustees are indigenous

people. Eight percent of India’s

population are Adivasis and fifteen percent are Dalits but an incredible sixty

percent of those displaced by the dam projects are Adivasis and Dalits (Roy

18).

“This July will bring the last

monsoon of the twentieth century. The

ragged army in the Narmada valley has declared that it will not move when

the waters of the Sardar Sarovar reservoir rise to claim its

http://www.goldmanprize.org/search/search.html

With activist Medha Patkar

to lead them, the Narmada Bachao Andolan began mobilizing massive marches and

rallies against the Narmada Valley Development Project, and especially the

largest, the Sardar Sarovar, in 1985.

Although the protests were peaceful, Patkar and others were often beaten

and arrested by police. Following the

formation of the NBA in 1986, fifty thousand people gathered in the valley from

all over India to pledge to fight “destructive development” in 1989. In 1990, thousands of villagers made their

way by boat and foot to a small town in Madhya Pradesh in defense of their

pledge to drown in the reservoir waters rather than move from their homes. Later that year on Christmas day an army of

six thousand men and women accompanied a seven-member sacrificial squad in

walking more than a hundred kilometers.

The sacrificial squad had resolved to lay down its lives for the

river. A little over a week later the

squad announced an indefinite hunger strike.

This was the first of three fasts and lasted twenty-two days. It almost killed Ms. Patkar, along with many

others.

The NBA has also taken a

more diplomatic approach to getting through to the government. They have submitted written representations

(complaints) to government officials such as the Grievance Redressal Committee,

the Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam, the President, and the Minister of Social

Justice and Environment Maneka Gandhi.

More often than not, their voice goes unheard and unacknowledged.

“No one has ever managed to

make the World Bank step back from a project before. Least of all a ragtag army of the

poorest people in one of the

world’s poorest countries.” -

Arundhati Roy

The demonstrations, protests, rallies, hunger

strikes, blockades, and written representations by Narmada Bachao Andolan have

all made an impact on the direction of the movement to stop the building of

large and small dams along the Narmada.

Media attention from these events has taken the issues from a local

level to a more national scale. The NBA

was an integral force in forcing the World Bank to withdraw its loan from the

projects by pressuring the Bank with negative media attention.

“Big Dams are obsolete…They

lay the earth to waste. They cause

floods, waterlogging, salinity; they spread disease.

There is mounting evidence that

links Big Dams to earthquakes.”

Reassessing the environmental and social impacts of

the more than 3,000 dams slated for construction should be the first step the

Indian government takes in solving the country’s water management

problems. It should then observe the

recommendations proposed by those assessments, rather than ignoring them.

The country and the individual states could also

consider cheaper and more effective energy options that do in fact already

exist. In fact, “A task force set up by

the Madhya Pradesh state government suggested alternatives such as demand

management measures, biomass generation, optimum use of oil-based plants and existing

dams, and micro-hydro plants” (www.irn.org/wcd/narmada.shtml).

According to renowned irrigation expert K. R. Datye,

a comprehensive review of the yield of the land, taking into account the water,

energy, and biomass availability is required.

Datye highlights the need for regenerative water use for agriculture,

using local water resources. Water from

outside (i.e. dams) is used to restore vegetative cover to degraded land and to

recharge ground water aquifers that are badly depleted, to a point where water

and energy balance can be maintained (www.narmada.org/sardar-sarovar/ecotimes.alternatives.html).

The following watershed management strategies are

traditional practices that have been revived by local communities in the states

of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Gujarat with the help of Non-Governmental

Organizations and state government programs.

|

Alwar District, Rajasthan |

Revival of old and

building of new water harvesting structures coupled with formation of gram

sabhas for equitable water distribution has transformed the people of the

semi-arid, drought prone district. Awarded the "DOWN TO

EARTH-JOSEPH C JOHN AWARD" for India's most outstanding environmental

community. |

|

BanniGrasslands Kutch Dist., Gujarat |

A complex rainwater

harvesting system developed over centuries by the Maldharis of Banni

grasslands is threatened by natural factors and man made interventions. |

|

Jhabua District, Madhya Pradesh |

MP state government's

emphasis on participatory management, trans-parency and decentralization in

implementing watershed development programs sets an example that could be

replicated all over India. |

|

Thunthi Kankasiya & Mahudi, Dahod Dist. Surendranagar District Devgadh, Junagadh District |

Villages in Gujarat that

have taken watershed management measures have enough water for drinking and

even irrigation in the middle of the most severe drought of this century. |

http://www.narmada.org/ALTERNATIVES/index.html

Alternatives to dams do exist and

should be considered seriously.

“India:

Peaceful Demonstrators Against the Narmada Dam Project Arrested, Beaten, and

Intimidated by Police.” The Sierra

Club: Human Rights Campaigns. 1999.

<http://www.sierraclub.org/human%2Drights/india/index.asp>

“Medha Patkar.” The Goldman Environmental Prize. 1992.

<http://www.goldmanprize.org/search/search.html>

Narmada River page. International Rivers Network. 1996-2000.

<http://irn.org/programs/narmada/map.html>

Roy, Arundhati. The Cost of Living. New York: Random House, Inc. 1999.

“The Sardar Sarovar: A Brief

Introduction.” Friends of the River

Narmada. 2000.

<http://narmada.org/sardarsarovar.html>

Shruti

Mukthyar. “Alternatives.” Friends of the River Narmada. U of Wisconsin-Madison: Institute for

Environmental Studies. 2000.

<http://narmada.org/ALTERNATIVES/index.html>