STRESS

AND THE DEVELOPING Introduction |

|

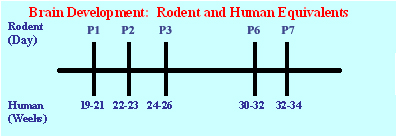

The rodent is a good model to study the repercussion of early life adverse environment. However, the developmental time frame of the brain development and LHPA physiological function needs to be considered when relating animal studies to human development. In humans, excluding the cerebellum and hippocampus, neuronal proliferation is essentially completed before 24 weeks gestation. Beyond 24 weeks, glia continues to proliferate and oligodendroglia maintain ongoing myelination, with a peak in brain growth occurring near term. In contrast to humans, rodents experience their brain growth spurt after birth. It is estimated that on postnatal day 10 the rodent brain is roughly equivalent to that of the full term human brain of 38 to 40 weeks post-conception. Extrapolating from this model, the brain of a rodent pup at birth (P1) corresponds to that of a human fetal brain at or near 19–21 weeks gestation. The P2 animals approximates that of a 22-23 week human in terms of neurodevelopment, the P3 corresponds with that of a 24-26 week human, and the P6 pup to that of a 30-32 week human. Given these parallels, the neonatal rodent pup provides an ideal model in which to investigate effects of stress and of prolonged, tapering course of neonatal corticoid exposure on the developing brain.

|

An important consideration is that the ability

to respond to stressful events develops after birth in

the rodent. Animal studies suggest that early life events

can alter the developmental trajectory of brain circuits including

those that are critical for behavioral and hormonal responses elicited

by changes in the environment that can be construed as stressful.

Epidemiological studies in the human suggest that there is a

link between adverse early life experiences and psychopathology (e.g.

depression, anxiety, drug use). Simply being touched and held during

the first few years of childhood may set up positive stress-response

patterns that last a lifetime. |

|