Hogarthian Lines

Soulful grace neither intended nor implied.

Hogarthian Lines

Soulful grace neither intended nor implied.

Slow Work

The other morning my 7 year-old son and I took a break from riding bikes together to his school and instead we walked the 1.2 miles. Along the way, we talked about things we saw – I was marveling at the slate roofs on old houses, while he was fixated on the apple blossoms and flowering dogwood making their first appearances. At some point I realized we hardly ever make these observations when we’re cycling – in part because there is more to pay attention to, like cars, the hill we’re climbing, how aero we descend, etc. – but mostly because walking is slower and there are more moments.

I don’t consider myself particularly fast or slow, and so my motivation here isn’t to reinforce what already comes naturally to me. Rather, it is to make that point that whatever one’s natural speed is, it can be intellectually healthy and rewarding to slow the pace to allow for more moments, more connections. This seems to fly in the face of external forces and internal motivations that say “Hurry!” We seem to have internalized the notion that putting numbers on the board in the form of papers in the cv is a true measure of success rather than one of many convenient indices that administrators (and occasionally peers) rely upon to evaluate our success. But forget for a moment about number of publications, h-index, impact factor, &c. and ask yourself whether there is more to what we do than simply shoveling those numbers around. I am in the natural sciences to try to understand something about the natural world…to “push back the frontiers of knowledge” as it was put to me on day one of graduate school by Philip Ulinski, the colorful chair of Organismal Biology & Anatomy at Chicago. (I think about Phil often, even today. If he caught you taking the elevator up to your office, he would stand outside it staring at you as the doors closed and then race it up to your floor and be waiting for you as you came out. He’d greet you with a smile and gently remind you to exercise the body as well as the mind.)

May 11, 2016

Wait – WHAT?

Go slower? Why? Going slower means it takes longer for specimens, observations, and hypotheses to make their way into the academic and public sphere … and it increases chances of getting scooped. Why not simply get it done quickly and mostly right, publish it (hopefully somewhere fast and good), and let science sort out any shortcomings? This latter approach certainly has its advocates, or at least practitioners, and it can be an effective strategy if numbers matter, if the bar to publishing a manuscript is low, and if there is no penalty or paper trail for rejection. So if Journal A rejects the manuscript, then roll the dice at Journals B, C, or D...perhaps one of them will accept it. (I’ve received several such déjà revues recently – a manuscript I’m asked to review again after having already reviewed it for another journal that didn’t accept it, often in the same form as it was in the original submission.) The result is papers that come out quickly and in legion, reading like newspaper copy. Some folks write faster than I can read.

If a journal does publish a quickdraw manuscript that is superficial or has avoidable errors in it, then you might well ask what my problem is—the data are now available, and I can critique the analysis if I’m so inclined. Absolutely. I or someone else can do that, but we all have our own research questions that fully occupy our intellectual energies, I’m reluctant to engage in that sort of paper unless it presents an opportunity to make a more general conclusion (a few of my own papers are, explicitly or implicitly, fleshed responses to other papers).

It is my responsibility to present observations and inferences about the natural world as fully and completely as possible given the circumstances. There’s no argument that humans are imperfect and don’t have access to all the data that are available now, or that will be in the future, and so perfection is obviously an unfair expectation of a research manuscript. However, what I’m advocating is not perfection, but rather the act (or attempt) to make the manuscript as good as it can be given one’s own limitations, both in terms of abilities and the data at hand. For this, time is the critical ingredient.

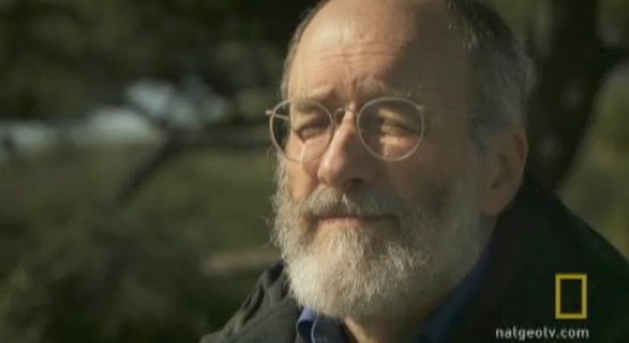

The Sand Walk

I visited Down House in 1993 on the front end of an expedition to the Sahara Desert. We were shown the Sand Walk, which is a path around the perimeter of a wood that Darwin would use for thinking. Rumination. In the photo above, which was snapped by my friend Hans Larsson, I was probably not thinking much more than that it was cool to set foot where Darwin had. I don’t think I much appreciated the mental exercise that Darwin engaged in on that path. But I would get a better sense of it later on that expedition, when we were completely isolated from everything familiar to us for months on end. There were no phones, no wifi, email, letters, radio, or anything else. Just wind, sand, stars, and lots space to roam in physically and mentally. It was wonderful.

Apple blossoms on the campus of the University of Michigan, May 2016.

The Tramp keeping up (for the moment) on an assembly line in Modern Times (1936).

A Slow Devouring

My former student Mike D’Emic had a buddy who wrote a story about a group of friends that met weekly to read a page or two of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. This Slow Devouring of the 600+ page text would take the group years to complete. Here’s what the author, Steve Macone, said about this rather measured pacing:

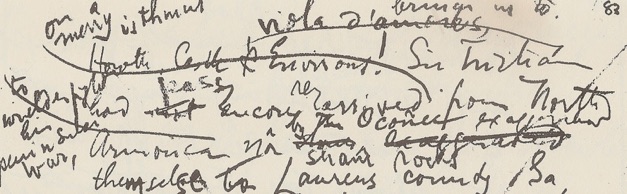

An early draft of the first sentence of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Note the “Howth Castle & Environs!” opening, which was heavily modified later. Image from Peter Chrisp’s blog.

Its complexity prevents any attempt at a gritty rolling-up-your-sleeves-and-just-getting-it-done tactic; its style protects it from revealing itself through the profligate attentions of the college student during an all-nighter, an impenetrability that precludes the CliffsNotes approach.

The history of life on our planet is without doubt much more complicated than Finnegans Wake, but the projects that individual researchers carve out tend to be much smaller by comparison. But what if we nevertheless treated each project more like a little masterpiece in the making, something that we toil over, hone, over an extended period of time? What would be gained?

Little-picture gains: nearly every aspect of the process (of, say, describing a fossil) would benefit from additional time – or at least without the pressure of racing against the clock: examining specimens, photography, coding characters and scoring the matrix, outlining the manuscript, writing the manuscript, story-boarding figures, creating figures, proofing, &c., &c. More time committed to each of these steps helps to eliminate errors by virtue of the additional contact hours with the subject matter but even more so if there are specific checks made. How many people who create a character-taxon matrix for phylogenetic analysis actually commit time to check it for errors – i.e., to go through the matrix to make sure that the scores accurately reflect what the investigator thinks? What about checking measurement tables? Correspondence between abbreviations in figures and the legends that accompany them? Whether figure call-outs correctly refer to the intended figure? There are many such small checks that can be made. Errors can still creep in, but fewer of them do. All of this improves the quality of the work and of the literature in general.

Big-picture gains: working on a project over a longer period of time allows you to think about it more. More connections can be made and richer insights derived. How many manuscripts settle for a punch line that sounds like “first X from Y” or “most complete A from B”? These are not necessarily wrong, but they are superficial, and qualified superlatives are temporary designations.

The Sand Walk at Down House, England, September 1993.

It is difficult to find the time and space to think. With so many calls on our attention, from administrative duties, teaching, and outreach to personal obligations we have to our family and friends, we should be doing something. I certainly struggle with this, and part of the motivation for writing this piece was to spend more time thinking and working through this.

Without recourse to a Sand Walk or the occasion to live in a remote place for an extended period of time, it can seem difficult to build thinking time into one’s life. But really all that is required is simple, uncluttered mental space within which to wander. There is a wonderful segment in the “Waking the Baby Mammoth” documentary during which my colleague Dan Fisher talks about the role of creativity in his work and where ideas come from. As he says, it’s not magical. Dan uses his walk between home and the museum – about 20 minutes each way – to work through problems. A good part of stratocladistics was developed that way. I too used to walk into work (before kids), and much of my anatomical terminology paper was written on foot in 40-minute segments. There are other opportunities. A long drive with the radio off. Jogging without earbuds. Subway ride without earbuds. Anything without earbuds. An airplane flight. A comfortable chair at night. A journal. Raking leaves. And so on. The main thing is to give yourself time. Your brain will do the rest.

Dan Fisher making connections.