"We are now become so habituated to fire, that

the soldiers seem to be indifferent to it, and eat and sleep when it

is very near them."

-Thomas Anburey

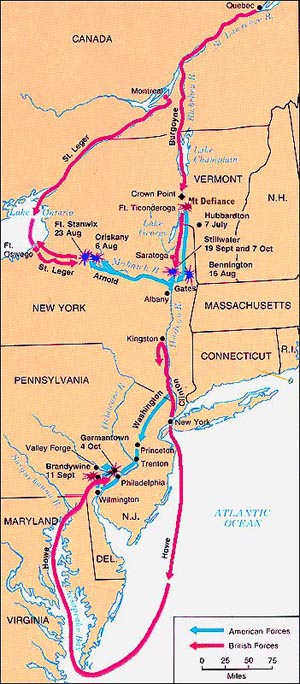

Marching south from your winter encampments in Quebec, your regiment,

part of a force of nearly 7,200 men (although half of them are German

mercenaries,) under General Burgoyne on June 3, 1777 moves down to meet

General Howe's Army (moving North from New York) in Albany. (Barnett,

217)

Just as at home, the day begins early: marches begin at dawn, and keeping

in tight ranks, you advance at a steady clip of seventeen to twenty

miles a day. However, the farther south you move, the less hospitable

the landscape becomes-the New England woods are old and dense, creeks

and marshes cut through the terrain, and the sweltering summer heat

invites clouds of flies and mosquitoes that seem to hover over your

lines. As much time is devoted to felling trees, clearing roads and

building bridges (at least forty by your count), as is spent advancing,

and everyone in the company retires to their canvas tents exhausted

from the day's labors. (Frey, 103)

The halting pace has also made you easy targets for American guerillas

(the best marksmen in the world,) who wait with their hunting rifles

under cover of trees or fences to shoot honorable British soldiers in

the back. It is a testament to British training methods that you are

able to keep in line, even with American bullets whizzing towards your

mounted officers. Usually, these ambushes last only a few minutes, when

the colonists are spotted and killed, or more often, the rebel slips

away into the shadowy landscape. (Barnes, 60)

Even more alarming than these dangers, is the premature

depletion of salt rations due to the army's suspended progress. Having

failed to reach the Hudson River by August, you have begun to subsist

on simple cakes of flour and water, baked on stones in front of small

fires. (Frey, 103)

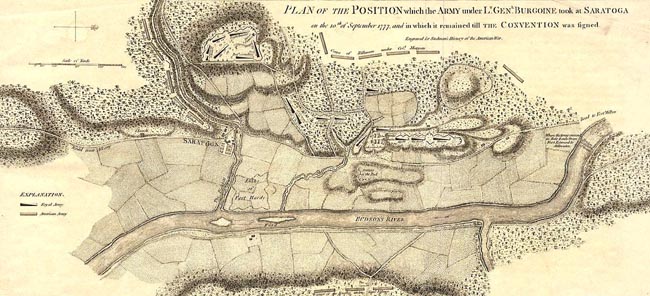

After engaging in several costly and dispiriting battles, and accumulating

many hundred British casualties, your force, led by General Burgoyne,

is attacked American General Horatio Gates' army at Freeman's Farm, halfway

between Saratoga and Albany. As traumatic as you find the action of the

battle, the aftermath-filled with the screams of wounded and dying comrades-is

exponentially more excrutiating. Officers and infantrymen-some from your

very own regiment-are bloodied by musket-balls, lacerated with bayonet

wounds, and disfigured by cannon-fire. Serving several hours on burial

detail, you can hardly keep from passing out as you walk around moaning

bodies-dying soldiers begging in German and English for some sort of nourishment.

(Frey, 103-104)