| During

the annals of the Depression, as the city's deficit was nearly

$300,000,000, Capone was making out. The annual income of his

operations was estimated at $100,000,000 a year (Allsop,

199). There didn't seem to be any money in politics; indeed,

there seemed to be a vacuum sucking the money out of politics.

Mayor Cermak found the deficit so crippling that he said publicly

that the city might have to shut City Hall down entirely. Instead, Chicago cut down its expenses by slashing city employee wages and not

paying public school teachers, many of whom received only six

weeks' salary over nine months (Allsop,

197). Logically, during a period when money could not be

made legally/ legitimately due to the Depression, many sought

illicit means for supporting themselves. And so politicians

largely invented ways to turn a profit in their careers. Racketeering

became very common, and many politicians received profit for

ignoring the operations of organized crime leaders like Capone. |

Capone

and Stege, the Chicago Chief of Police (Citation).

|

|

Mayor Thompson

(Citation).

|

"Big

Bill" Thompson, two-term mayor of Chicago during the

period of prime expansion of Capone's empire, provides a perfect

example of political corruption operating at even the highest levels

of the city. Thompson himself had connections to the Capone

ring--one of his best friends was "Big Jim" Colosimo,

head Chicago gangster at the time Capone moved to the city.

Colosimo was Chicago's "prostitution czar" and, as we have noted in our Capone

Biography, Big Jim was promoted to a police precinct captain

by Thompson after swinging a number of voters to Thompson's

side (Allsop, 204). As Prohibition historian Kenneth Allsop writes,

"Without stretching the logical sequence too far, to

Thompson may be attributed Capone's eventual terrorization

of Chicago, for it was to protect the new prosperity conferred

upon him by the Thompson ring that Colosimo imported Torrio,

who in turn imported Capone" (Allsop,

204). Thompson later secured a friend in Congressman Fred Lundin,

as corrupt a politician as Thompson himself. The two even

tried to take over the city's judiciary, angered by the fact

that some judges refused payoffs. The plan failed, however,

when they were exposed by the press.

|

In a few instances, Thompson

even turned to violence as a means to impose his political will.

Democratic Alderman John Waters, who had controlled the 19th Ward since 1888, decided to run again in 1924.

Mayor Thompson, however, had a new agenda: the election of Anthony D'Andrea,

a notorious and well-known pimp, into the position. A bomb was thrown

into Powers' house, but Powers and his family were unharmed. Powers retaliated with a bomb of his own, thrown

by his men into a meeting of D'Andrea's supporters. Powers eventually

won the election, but the violence didn't stop there. D'Andrea's men

walked the streets with sawed-off shotguns, searching for Powers'

people. Death threats were sent to Powers' family. Eventually, Powers

struck the final blow--D'Andrea was killed later that year. Throughout

all of this, there was no police intervention in any of the incidents,

and federal investigation was deferred constantly (Allsop,

208). The cops, clearly, were just as crooked as the politicians, who were just as crooked as the mob. Indeed, during this period, the three seemed to form an interpenetrating web of crime.

This interrelationship

of organized crime and criminal politics continued to grow throughout

the 1920s as Prohibition continued, and as it continued to be more flagrantly

violated and exploited. After Thompson took a term off from 1922-24,

the Torrio-Capone machine was brought in to organize gun squads

to ensure Republican victory (Thompson's return to office in 1924).

(Allsop, 209). The police regularly

were paid off by Capone's men, and, in turn, they largely ignored

Capone's flagrant violations of Prohibition, prostitution, and gambling

laws, and even the severe acts of violence that they sustained.

|

Mayor Cermak (Citation).

|

Thompson's career

eventually did end, in 1930, and his successor, Mayor Cermak,

was told upon taking office that the 1928 and 1929 tax assessments

"reeked with fraud" (Allsop,

197). Clearly, Thompson had been embezzling tax

money, channeling it to God-knows-where. Mayor Cermak was

told at a special session of the State Legislature that the

only solution may be to place the city under martial law.

The plan was never carried out, and Capone's dominance of

the city continued throughout the Prohibition era.

|

| Nonetheless,

there were at least a few straight cops in Chicago. Eliot Ness,

who organized a group of law enforcers later mythologized as

the "Untouchables," was one of them. As in the film

The Untouchables, and the television show the film was based

on, Capone's lieutenants sent death threats to Ness, and hired

an assassin to wipe him out (the assassin failed). Earlier,

they tried to pay him off. After Ness refused their bribes,

a newspaper article called him "Untouchable." The

myth of the "Untouchables" was built around this fact.

Ness and the Untouchables conducted frequent raids on Capone's

breweries, often causing violent confrontations. Ness, however,

was the exception in his not being pocketed by Capone (Tucker,

12). Eventually, Ness's group collected sufficient evidence

against the Capone ring to send him to prison (see our pages

on Al Capone for further information).

After the victory against Capone in Chicago, Ness was moved

to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he continued to conduct raids on

breweries until the end of Prohibition. In one of history's

supreme ironic jokes, Ness, ever the poster child for Prohibition

enforcement, struggled throughout his life against a drinking

habit (Tucker, 5). |

The

Untouchables DVD cover (Citation).

|

|

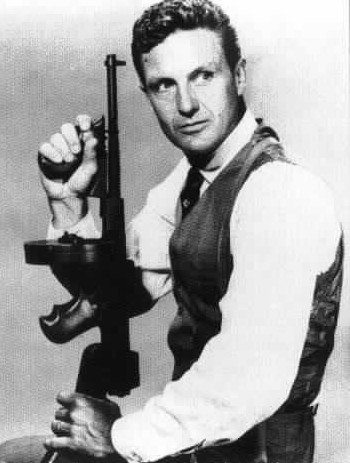

Robert

Stack as Elliot Ness from The Untouchables television

show (ABC) (Kassel).

|

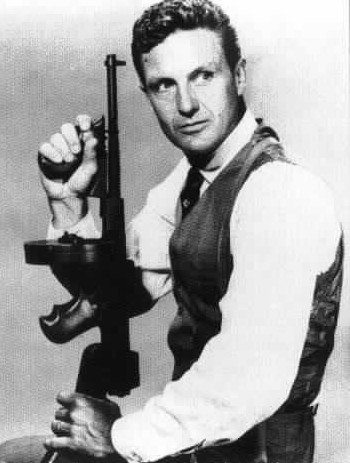

A

picture of the real Elliot Ness (Corrigon).

|

|