The women who lived during the Crusades were faced with many challenges and opportunities. Although the society of the time was patriarchal, it is a serious misconception to think of the medieval woman of this era as the "Lady in the Tower" remote from the affairs of everyday life. An expanding economy coupled with the large number of wartime casualties and absence of men in the East allowed women to assume many more roles than earlier medieval domestic options.

Several women from both East and West played prominent roles in the Great Crusades. Anna Comnena (1083-1153), a daughter of the Alexis I, wrote the history of her family, the Alexiad after she failed in a coup to put her husband on the Byzantium throne instead of her brother; she depicted the knights of the first crusades not as saviors but as looters who turned greedy eyes to the gold, enamel, and art work of Byzantium.

Eleanor of Aquitaine, (1120-1204) took the cross with her first husband Louis VII of France and scandalized Europe by leading 300 of her women dressed as amazons and a thousand of her knights from her duchy in the armies of the Second Crusade. Even though she insisted that the women went along to "tend the wounded," Eleanor insisted on taking part in strategy sessions and sided with her uncle Raymond of Antioch instead of her husband Louis on the question of whether to attack Jerusalem. Louis settled the argument by insisting that she accompany him to Jerusalem. The King and Queen of France went home on separate ships, and back in Europe after she gave birth to a daughter, Eleanor insisted on a divorce and married Henry II of England.

During the third crusade, Shagrat al-Durr (d. 1259) wife of the Egyptian sultan, organized the defense of the realm during her husband's illness, became sultan due to the support of the army on his death, and defeated Louis IX, King of France at Damietta. Her overlord the Caliph of Baghdad refused to let a woman ascend the throne and sent a Marmalul solider, Aibak, to take her place. Shagrat then seduced and married Aibak and ruled happily with him until he wanted to take another wife. Shagrat had him murdered, but is killed herself by Aibak's son and former wife.

The paladins who created the Frankish Kingdoms of the East after the First Crusade intermarried with the women of the East, particularly Armenian Christians. One of the children of these unions was Melisende, the daughter of Baldwin II who married Morphia while Count of Edessa. Melisende (1105-1160), Queen of Jerusalem, ruled the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem jointly with her husband or son or vied with them for supreme power. (Women in History Website). The experience of women such as Anna, Eleanor, Shagrat and Melisende proves that women were willing to seize power when the opportunity presented itself. All of these women provoked strong masculine response and found it easier to exercise power through a husband or son.

Eleanor and Shagrat were strong women who were able to assert their independence because of their strong wills and the resources they commanded, but after Eleanor's adventures during the Second Crusade, the Church officially discouraged women rulers from taking vows of crusading. Western women did continue to accompany men to the wars, as the sister and wife of Richard the Lion-Hearted did in the Third Crusade, but they went along in a private capacity. The only women that the Church officially approved for part of the Crusaders army was the washerwomen. Why the washerwomen? They played a vital role in washing clothes to prevent the spread of lice, and they were usually too old to be temptation for men.

The women who were left behind had to actively rule their estates and defend their castles. These chatelaines had to hold the family lands together for themselves and their children. Governing in their husband's name, these women engaged in legal transactions, oversaw agricultural activities, collected moneys for ransoms, and brought up the children. (Women in history website) Strong women who ruled as regents kept whole kingdoms together. After being imprisoned by her second husband Henry II for supporting her children in a dispute, Eleanor of Aquitaine ruled England as regent for her son, King Richard the Lion-Hearted, during the Third Crusade. Blanche of Castile (1187-1251). Eleanor's granddaughter, had her son Louis IX (St. Louis) crowned king of France when her husband died, supervised his education, and functioned as his regent when he went on crusade and ruled jointly with him on his return.

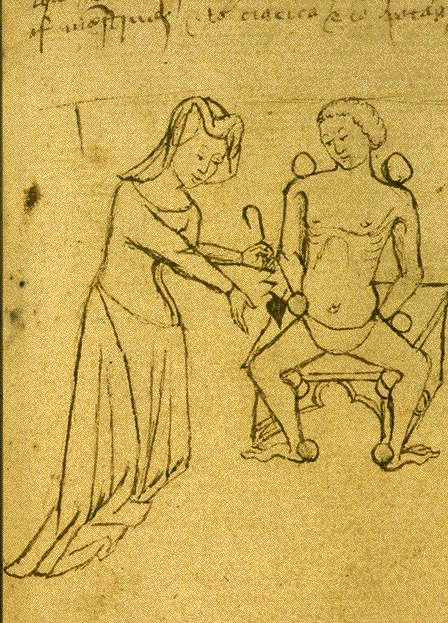

Even though women were often idealized as either a virgin/mother or reviled as a temptress, medieval manuscripts depict women from all levels of society in a wide variety of active roles. (Salisbury, 1985) There are even rare cases of trial by combat between men and women. (Hodges, 1997).Besides predominating as workers in the textile and silk-making trades, Frances and Joesph Gies (1980) list over 100 crafts, such as shoemaker, tailor, barber, goldsmith, baker, armorer, or chandler where women worked alongside men. Women also controlled the important tasks of manufacturing and the sale of food and beverages. On the manorial estates, women worked with the men in the fields, hauled the water and handled the livestock, prepared the food and did the housework, including spinning cloth which paid the feudal dues or could be sold for outside money (Washington, 1985). Medieval women functioned as teachers, nuns and abbesses, artists, writers and composers, merchants and alewives, washerwomen and prostitutes. One of their most important and respected roles was that of healer and midwife. The new Universities of the twelfth centuries, with their medical schools which drew upon Arab learning, downplayed this role (Booher 1997).

Queens, abbesses, and widows functioned as patronesses of culture. McCash states that since patronage for women was sanctioned, it provided "rich opportunities for women to make their voices heard" (McCash, 1). Eleanor of Aquitaine herself commissioned art in the Great Abbey of Fountevrault. Her daughters promoted literature and culture all over Europe. Marie de Champagne was the patroness of Chretien de Troyes who created some of the great Arthurian romances; her sister Mathilda of Saxony commissioned romances and introduced courtly poetry into her husband Henry the Lion's circle; their sister Leonor and her husband Alfonso of Castile welcomed troubadours and minstrels. The period of the crusades gave women the economic resources to promote cultural activities. Many other royal and noble women supported the copying and dissemination of books. Eleanor of Castile (d 1290), a Queen of England, included a scriptor in her royal apartments that employed both a writer and an illustrator to create books on saint's lives, Psalters, as well as books of romance.

Rich widows whose husbands died on crusade often commissioned works of art after raising children. Examples include Agnes, the countess of Bar, who was Eleanor of Aquitaine's sister-in-law though her marriage to Robert, brother of the king of France. Between 1188 and 1204 Agnes gave large gifts to a church at Braine, even getting glass from England, with the help of Eleanor, for stained glass windows. Agnes made sure that the artists depicted feminist themes. Topics in the windows include a Jesse Tree, a symbol often used by women, and a female personifications of the liberal arts. Despite gender restrictions, McCash states, "the pattern of female cultural patronage provides a growing awareness of women's worth and intrinsic value to society" (McCash, 33).

Chretien de Troyes states that that in composing the Arthurian romances he just elaborated on the basic material and interpretation that his patroness Marie, Countess of Champagne, wanted him to express. (McCash, 18). The livelihood of Troubadours often depended on pleasing their patronesses. After the death of her husband on crusade, Marie found herself in a harsh world where she had trouble collecting taxes and enforcing marriage agreements that they had made for the children. McCash adds that because of the difficulties involved in ruling alone, Marie was especially interested in sponsoring works that enhanced the "power or reputation of women."

Influenced by Arab love songs, troubadours flourished at the courts of Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Noble women themselves such as Marie de France and the female troubadours in Occativa in France between 1160-1260 composed romances and songs of love. The poems of women were more personal and candid than those of their male counterparts. Here in an abstract from a poem (translated by Meg Bogin), two sisters Alais and Iselda discuss candidly their feelings about marriage:

Lady Carneza of the Lovely Gracious Body

give some advice to us two sisters

shall I marry someone we both know?

or shall I stay unwed? that would please me,

for making babies doesn't seem so good

and it's too anguishing to be a wife (p.144)

The advice Carenza gives shows that no matter how active their role, women were still encouraged to either marry or become nuns:

I therefore advise you, if you want to plant good seed

to take as husband Coronat de Scienza

from whom you shall bear as fruit glorious sons

saved is the chasity of she who marries him

Romantic songs and stories were popular with women all over Europe. After all , love is the opposite of war and these songs were good escape literature. McCash quotes from Denis Piramus:

The lais most usually please women

with joy they hear them willingly

for they are in accordance with their desire

Kings, princes, courtiers,

counts, barons and vavasserus

like talkes, songs, and fables

and good verses which are amusing (p.24)

This world could take time out to be entertained.

Bogin, Meg, The Woman Troubadours

Booher, B. "Beyond the Birthing Room: The Work of Monica Green." Online. Internet. Available http://www.adm.duke.edu/alumni/dm3/green.txt.html

Bornstein, Diane. The Lady in the Tower, Medieval Courtesy Literature for Women

Caviness, Madeline H. "Anchoress, Abbess, and Queen: Donor and Patrons or Intercessors and Matrons?" The Cultural Patronage of Medieval Women p. 105-154.

Crusades, (Video-tape), History Channel, October 4, 1997

Gies, Frances and Joseph. Women in the Middle Ages. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1980

McCash, June Hall. "Medieval Patronage of Medieval Women: an Overview," The Cultural Patronage of Medieval Women .

Parsons, John C. "Of Queens, Courts, and Books: Reflections on the Literary Patronage of Thirteen Century Plantagent Queens."

Salisbury, Joyce, (video-recording). Medieval Women

Modified December 8, 1997