Fights, Mysteries and Identity Politics: A choreographer's thoughts about the aesthetics of video dance work

by Petra Kuppers (this text formed part of a presentation at the Association of Theatre in Higher Education convention, Toronto, 1999)

|

Fights, Mysteries and Identity Politics: A choreographer's thoughts about the aesthetics of video dance work by Petra Kuppers (this text formed part of a presentation at the Association of Theatre in Higher Education convention, Toronto, 1999) |

| In 1999, I was asked by disabled visual artist and webmistress Ju Gosling to workshop a dance sequence with her and a non-disabled performance artist. Here are some of the thoughts that have shaped our work process so far. |  |

I have asked the dancers to try to work with their eyes closed, and to rely on sound and touch as the initiators of movement. In warm-ups, I ask them to focus on somatic knowledges that differ from the outside view of the body: they work with instructions to 'move as if all skin, all muscles, etc.'. I attempt to get the dancers away from the outer, visual image of their bodies, disabled or non-disabled. As they struggle to explore their differences without visual input, that sense which most clearly divides them up into different physicalities, a third moving person captures their touches and sways with a video camera.

The camera attempts to get close, and therefore has to move fast out of the way of feet or falling bodies. As the dancers get more comfortable with each other, and learn to thrust each other and the space in which they move, the camera person has to engage with this trust, and has to feel kinesthetically where the dance will go.

Watching the video, I can see the camera as a physical presence, not as the disembodied eye of classical cinema. Challenged to move away from visual means of gathering knowledge, the dancers' movements go through strange phases. The close-up camera catches the traces of fights: the fight against fear, the fight against stereotypes, the fight against staying in secure places.

Can I touch here? Will this induce pain? Where am I with the other's body? Who is leading? Who should lead?

Given the social differential between disabled and non-disabled people, these questions are fundamental to the choreography - they are not to be overcome. I am not interested in 'normalising' the disabled body into the same space as the non-disabled body, but I am trying to tease out implications of social categories, fears and politics on the close, physical, non-everyday level of dance work.

The fast, strange, distorted images of movement which result from our dance work challenge the viewer to understand what she sees: the camera is too close to fully reveal the situation. This close-up, the intimacy of the camera and the video screen, cannot be achieved by the conventional stage situation. A dance performance in a very small circle, with dancers nearly touching the audience, captures a similar engagement, but the strenuousness of the performance situation could be dangerous to some disabled dancers with pain-related impairments. Also, the live performance is limiting - only a few people can access it. A video dance as an installation in a gallery can reach a greater audience. It can be played and re-played according to the need or interest of the individual spectator, and allows different people to dance for different audiences.

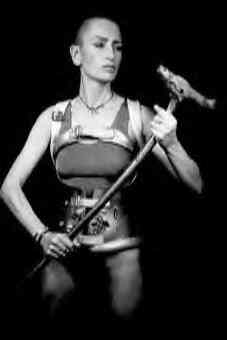

The specific meeting of dance and technology gives dance the chance to show us new constellations of bodies in movement. The close-up of the camera allows me to break through some the stereotypes that we have of each other, of our bodies, and to allow us to get nearer than the full, unified image would let us. The textures and hesitations of cloth, hands, orthopaedic braces, swirling hair and arching backs in contact with each other defy an easy political reading. No clear narrative is acted out by these bodies: we cannot see them as the disabled and the non-disabled artist, cautiously approaching each other in a metaphor for our political struggle. Instead, the fast cut images and their kinesthetic charge, their dance across the video screen, merges these two dancers at times into a melange of movement.

The video montage tries to recreate the experience of dancing, of moving wholly, focused on space, bodies, hesitations, encounters - too fast to step back into social categories. The spectator's access to these bodies is mediated, framed: we can see the traces of the live movements on the screen, but we are also aware how the view-point, the camera-eye itself is moving with the rhythm of the dancers. We are never outside the action, viewing it from a vantage point. Instead, we are in the dance itself, off-balance and implicated. The encounter between different physical experiences, different embodied lives create mysteries which are not resolved.

You cannot get the bigger picture.

If you as spectator are seduced by the camera into getting to dance with us in your act of viewing, we are dancing together. You give up your stable hold on seeing the dancers as others, as different bodies than your own. Instead, you can feel yourself taken up by the kinesthetic appeal of the moving camera joining the dance. We are moving towards a space where physical difference is exciting and interesting, and not swallowed up in the certainties of social meaning, and its boring distinction between normal and other. The sensuous meeting of moving bodies and a caressing, dancing camera can create this new dancespace, where the sensation of moving together in space, each differently but united in the will to collaborate, becomes more important than the need to know what body is moving where. This is the horizon of my choreographic desire.

The dance/installation project 'Fight' is in progress.