Hall's chapter also discusses both Letchworth and Radburn. I wouldn't worry about the minute details of each of these places, but a short answer is: Radburn had no substantive agricultural greenbelt (the most prominent green feature is the central green spine between the rows of houses). Nor did it have a critical mass of industrial employment, but rather is well-integrated into the larger commuting landscape of suburban northern New Jersey. Radburn is perhaps best known for its use of large blocks (superblocks, though not on the Corbusier design), cul-de-sacs, separation of pedestrians and roadway, and other fine-grained designs). It didn't embody the grander communal features from Howard's original ideas.

*the city is not just an economic place, but also a social place (and we will make bad plans and designs if we retain this narrow view of the city's function): "MOST OF OUR housing and city planning has been handicapped because those who have undertaken the work have had no clear notion of the social functions of the city." (59) "The city is a related collection of primary groups and purposive associations: the first like family and neighborhood, are common to all communities, while the second are especially characteristic of city life." (59) Further down, he writes: "social facts are primary, and the physical organization of a city, its industries and its markets, its lines of communication and traffic, must be subservient to its social needs.” (60)

* more broadly, the city is a rich, complex expression of human activities beyond the economic: "The city in its complete sense, then, is a geographic plexus, an economic organization, an institutional process, a theater of social action, and an aesthetic symbol of collective unity. The city fosters art and is art; the city creates the theater and is the theater." (59)

*primary vs. secondary relationships in a city: Mumford seems to reflect the then-popular distinction (described earlier by the German sociologists Tönnies and Simmel, and later by the Chicago School, e.g., Wirth, etc.) between the primary/direct relationships of smaller communities (Gemeinschaft) and the secondary/indirect relationships of big cities (Gesellschaft): "The city is a related collection of primary groups and purposive associations: the first like family and neighborhood, are common to all communities, while the second are especially characteristic of city life." [59] "One may describe the city, in its social aspect, as a special framework directed toward the creation of differentiated opportunities for a common life and a significant collective drama. As indirect forms of association, with the aid of signs and symbols and specialized organizations, supplement direct face-to-face intercourse, the personalities of the citizens themselves become many-faceted..." (59-60)

*limits to city size: one should not let cities grow unbounded (either in population or in land area): "There is an optimum numerical size, beyond which each further increment of inhabitants creates difficulties out of all proportion to the benefits. There is also an optimum area of expansion, beyond which further urban growth tends to paralyze rather than to further important social relationships." (60-1) and later: "Limitations on size, density, and area are absolutely necessary to effective social intercourse; and they are therefore the most important instruments of rational economic and civic planning." (61)

* Relatedly, one sees here echoes of Howard and Geddes in Mumford's regionalist view of achieving a regional balance between city and countryside by having a polycentric (polynucleated) region (rather than a dominant central city surrounded by subservient suburbs and rural villages): "In such a network no single center will, like the metropolis of old, become the focal point of all regional advantages: on the contrary, the whole region becomes open for settlement." (62) [and he goes on to praise Wright and Stein's design for Radburn as in this spirit]

* He concludes with an argument for conscious planning to achieve this new type of polynucleated region: "Instead of trusting to the mere massing of population to produce the necessary social concentration and social drama, we must now seek these results through deliberate local nucleation and a finer regional articulation." (62)

Interesting question. there are two elements here: (1) the land use mix of a community (and whether it is just residential or also includes commercial and industry?); and (2) the type of planning (e.g., master planning). I’ll focus mostly on #1.

Re (1): Yes, I do see that similarity between garden cities and technoburbs: both contain employment centers and not just residential districts -- and thus both differ from "bedroom" community suburbs. That said, the ownership structure, lack of an agricultural greenbelt, etc. of a technoburb are markedly different from Howard's idea of a garden city. Also: though technoburbs may have housing, shopping and employment, they tend to be rather open systems: many people in one "technoburb" will drive to many other places within the region (e.g., other technoburbs, edge cities, the central city) for jobs, recreation, shopping, etc. That for many planners is the conundrum of mixed-use planning: the (New Urbanist) hope is that people would all live, shop, and work in their own walkable mixed-use community, but they still regularly get in their cars and drive all around the region (both for work and non-work trips).

Re (2): I agree: technoburbs are not necessarily "planned" in the same master-plan style as garden cities (though some areas/components of these technoburbs may be heavily planned, these planning is likely done by many different public and private groups, not just one.)

I find it useful to remember the difference between the start of the 20th century (the era of Howard, Geddes and Mumford) and today: a century ago, the concern was overcrowded, over-powerful central cities, and the need for decongestion (e.g., Mumford’s regional balance) to counteract these centripetal forces. Now (in many regions, esp. SE Michigan), the concern is about struggling central cities with strong centrifugal forces of suburbanization (pushing out past the inner-ring into outer-ring exurbia).. (It’s also useful to remember that the “garden city” was a model of a better city, whereas the “technoburb” is the name created by an urban historian to describe a phenomenon.)

This passage from Fishman's Bourgeois Utopias is a useful summary of his “technoburb” idea:

"Kenneth Jackson in his definitive history of American suburbanization, Crabgrass Frontier, interprets post-World War II peripheral development as "the suburbanization of the United States," the culmination of the nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century suburban tradition. I see this development as something very different, the end of suburbia in its traditional sense and the creation of a new kind of decentralized city.

Without anyone planning or foreseeing it, the simultaneous movement of housing, industry, and commercial development to the outskirts has created perimeter cities that are functionally independent of the urban core. In complete contrast to the residential or industrial suburbs of the past, these new cities contain along their superhighways all the specialized functions of a great metropolis - industry, shopping malls, hospitals, universities, cultural centers, and parks. With its highways and advanced communications technology, the new perimeter city can generate urban diversity without urban concentration.

To distinguish the new perimeter city from the traditional suburban bedroom community, I propose to identify it by the neologism "technoburb." For the real basis of the new city is the invisible web of advanced technology and telecommunications that has been substituted for the face-to-face contact and physical movement of older cities. Inevitably, the technoburb has become the favored location for those technologically advanced industries which have made the new city possible. If, as Fernand Braudel has said, the city is a transformer, intensifying the pace of change, then the American transformer has moved from the urban core to the perimeter.

If the technoburb has lost its dependence on the older urban cores, it now exists in a multicentered region defined by superhighways, the growth corridors of which could extend more than a hundred miles. These regions, which (if the reader will pardon another neologism) I call techno-cities, mean the end of the whirlpool effect that had drawn people to great cities and their suburbs. Instead, urban functions disperse across a decentralized landscape that is neither urban nor rural nor suburban in the traditional sense. With the rise of the technoburb, the history of suburbia comes to an end."

Physical determinism - the assumption that physical forms (e.g., the shape and form of the built environment) determine social outcomes. The term is often used as a criticism or warning: i.e., don't assume that there is a one-to-one direct relationship between the physical form of a city and its social dynamics. By extension, don't assume that one can directly change or fix social problems through reconfiguring the built environment. That said, most of us are in the field of planning (or architecture, etc.) because we do think there is some connection between the physical and the social (albeit complex, and often indirect). If there were NO link between the physical and the social, then the role of planning and architecture would arguably be very limited. So, a wiser path might be: avoid the most crude and naive versions of physical determinism, but then figure out where the physical does shape the social, and focus your efforts there.

Herbert Gans, in an influential critique of Jane Jacobs ("Urban Vitality and the Fallacy of Physical Determinism," in Gans, People and Plans. New York: Basic Books, 1968; pp. 25-33), uses the term as a way of saying: perhaps Jacobs has misplaced much of the blame for urban renewal and the lack of urban vitality:

"Her argument is built on three fundamental assumptions: that people desire diversity; that diversity is ultimately what makes cities live and that the lack of it makes them die; and that buildings, streets, and the planning principles on which they are based shape human behavior. The first two of these assumptions are not entirely supported by the facts of the areas she describes. The last assumption, which she shares with the planners whom she attacks, might be called the physical fallacy, and it leads her to ignore the social, cultural, and economic factors that contribute to vitality or dullness. It also blinds her to less visible kinds of neighborhood vitality and to the true causes of the city's problems."

pluralism -

OED: “3. Polit. A theory or system of devolution and autonomy for organizations and individuals in preference to monolithic state power. Also: (advocacy of) a political system within which many parties or organizations have access to power. 4. The presence or tolerance of a diversity of ethnic or cultural groups within a society or state; (the advocacy of) toleration or acceptance of the coexistence of differing views, values, cultures, etc."

The theme of pluralism runs through many of the readings (Davidoff, Jacobs, Iris Marion Young, Leonie Sandercock, etc.). Davidoff argues for pluralism (with many voices, and many divergent and competing interests) as an alternative to a monolithic version of planning (with a forced, singular "public interest"). One can see variations on the idea of pluralism in discussions about diversity, multiculturalism, communicative action, etc.

Jürgen Habermas (born in Germany, 1929) is one of the most influential of philosophers/public intellectuals of the postwar era. (If this were a philosophy course, we would read his original writings, and see him as part of the famous “Frankfurt School” of social research, along with Horkheimer, Adorno, Marcuse, etc.). For planning his relevance is primarily in the influence of his ideas about democracy and communicative action on the rise of communicative action/collaborative planning. We read a piece by John Forester (who teaches planning at Cornell), who has used the ideas of Habermas to explore the role of communication, deliberation and public participation to create a more egalitarian, democratic planning. Planners are attracted to his ideas of the “ideal speech situation” and “inter-subjectivity” (discussion between subjects to come to a sense of understanding and truth) as ways that discussion/debate between different individuals and interest groups can collectively shape planning outcomes. (And critics of Habermas have attacked the “ideal speech situation” as naively assuming an even distribution of power and access.). This is why Bent Flyvbjerg and Tim Richardson (in "Planning and Foucault: In Search of the Dark Side of Planning Theory") were critical of Habermas, and instead turned to Foucault. for more, see, for example, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

German architect who became (in)famous as the chief architect under Hitler and the Nazis. Designed several prominent Nazi buildings. Had ambitious plans for the reconstruction of Berlin to represent the grand aspirations of the Nazi “1000 year empire” -- most of these plans were never realized, as the German nation turned its attention and resources from nation-building to warfare and armaments production in the late 1930s. He mostly came up in this class through Peter Hall’s chapter on “The City of Monuments”. We didn’t cover much about Speer, but it’s worthwhile to know his role as the chief Nazi architect.

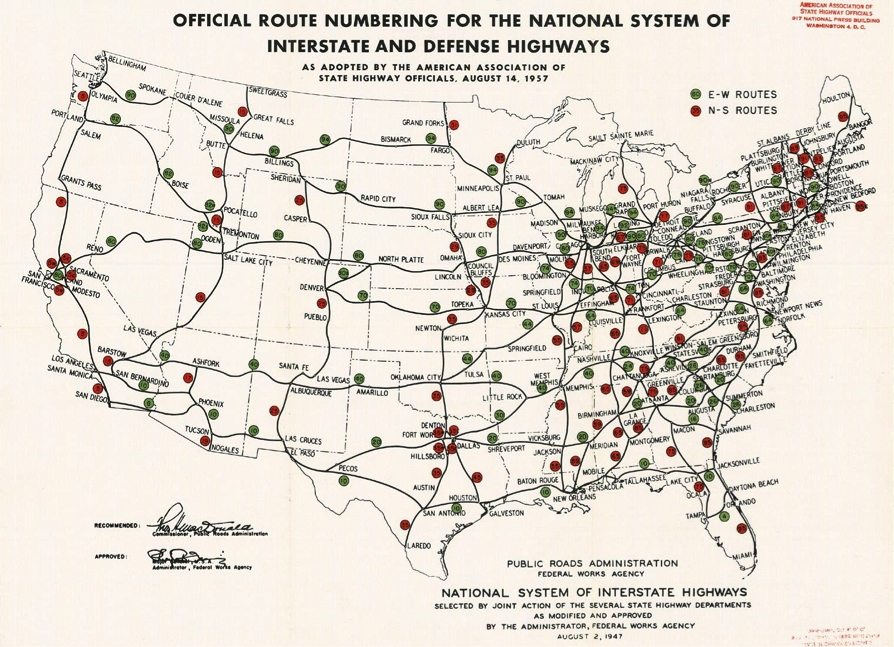

It was a landmark effort to build a nation-wide network of interstate highways. It involved massive amounts of money (and concrete/asphalt), and was seen as a crucial element of the rise of postwar automobility (which in turn was linked to suburbanization and the growing use of freight truck traffic). Significantly, the federal government paid for most of the costs, and was a model of federal-state partnerships in infrastructure building. Can been seen as part of a larger postwar effort to integrate the various American regions together in a single network. It was also known as the “National Interstate and Defense Highways Act,” and the military benefits (real or rhetorical) of having an integrated network of interstate highways (during the Cold War) was part of its marketing (and the US President at the time, Dwight D. Eisenhower, was a WWII general/hero). Indeed, the system was later renamed the "Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways." More info: “Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956: Creating the Interstate System” (alt link).

Interesting question -- I hadn’t thought about the connections between the two. [That said, in the classroom we treat the various styles of planning (comprehensive, incremental, advocacy, equity, strategic, communicative action) as pure types, while in the field, planners naturally combine and blur the boundaries. (I.e., these are useful analytical categories for understanding, but may be less distinct categories for practice.) ]

Is communicative action a necessary part of strategic planning? I don’t think so: it could be a useful part, but I also see many situations where the streamlined, top-down efforts of strategic planning collide with the deliberative, process-oriented, participatory nature of communicative action. Be sure to differentiate between communication as two-way deliberation/citizen participation/empowerment (what we usually think of when we talk about communicative action, a la Healey, Innes, Forester, etc.) and communication as instead one-way communicating/marketing the benefits of a strategic plan.

Can elaborate on your question so I can give a better answer?

Mel Webber (who taught transportation planning at Berkeley for many years) observed what he saw was a fundamental change in the role of place in society: where communities were once bounded by place (fixed in place), we now live in a highly mobile society where our relationships/networks/social ties are no longer always (or even mostly) physically nearby. Hence the idea: “community without propinquity” (physical proximity).

In this contemporary era of social media, internet, etc., this idea may seem commonplace -- but Mel was writing in the early 1960s. The piece we read by Webber, “The Post City Age,” addresses this growing divide between what we once thought of as cities and the new “post city” age. For the modern citizen, “how little of his attention and energy he devotes to the concerns of place-defined communities.” He “lives in a life-space that is not defined by territory and deals with problems that are not local in nature. For him, the city is but a convenient setting for the conduct of his professional work: it is not the basis for the social communities that he cares most about.” [477]

(Note: there are interesting similarities between Mel Webber’s view of these new social networks and Fishman’s description of the “technoburb” -- see #10 above.)

the property contradiction comes from the article by Richard Foglesong (a short excerpt from his book, Planning the Capitalist City). It is the contradiction between the social character of land and its private ownership and control: capitalism both needs planning, but also threatens planning. This contradiction does not invariably lead to collapse, but at least to tension and political conflict. (and one could argue that one role of planners is to manage this contradiction).

Why does capital (i.e., businesses, firms) have an interest in socializing the control of land? (1) to cope with the externality problems of land as a commodity; (2) housing, etc. for the reproduction of labor power. (3) to build infrastructure used by capital as a means of production. (4) coordinate efficient spatial circulation of infrastructure (i.e., transportation). Yet capital also restricts the social control of land.

Overall, the concept of the contradiction is useful because it gets us beyond the overly simplistic sense that the private sector always resists government intrusion, regulation, planning. Instead, businesses both resist and want government involvement in the private sector. (One sees this in the housing market, in infrastructure, in redevelopment projects, zoning, etc.) This is why I assigned Foglesong’s writing in the session on arguments for & against planning -- because he helps us understand why individuals and organizations can seemingly be pro- and contra-planning at the same time.

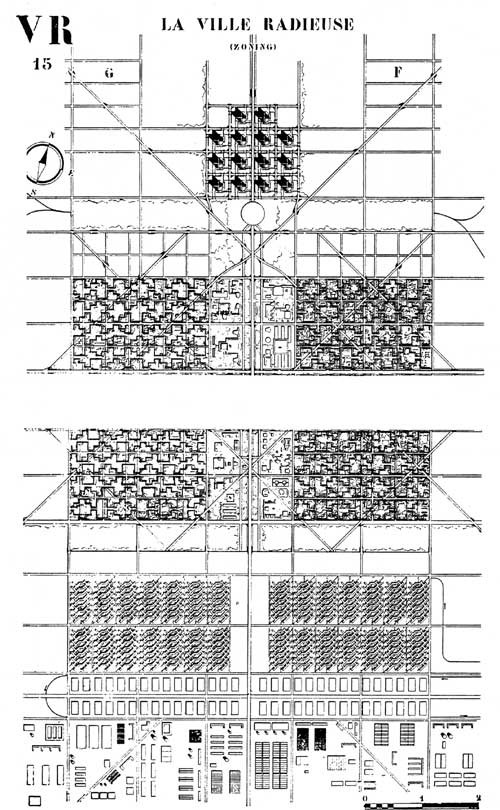

Fishman (in his book Urban Utopias in the 20th Century) examines the intellectual history of three visions of the city: Howard’s garden city, FL Wright’s Broadacre City, and Le Corbusier's Radiant City. “social thought in 3 dimensions” refers to the expression of broader social ideas and debates (over social organization, scale, democracy, order vs. freedom, etc.) in architecture, design and city building. Wright stressed an American decentralist view (Jeffersonian democracy?) and individual ownership; Corbusier went to the other extreme, with a highly organized, centralized, hierarchical society and the role of technocratic experts to turn chaos into order. One might see Howard somewhere in between: a hybrid of communal and private ownership; a mix of cooperation and competition; a medium-size scale (the garden city of ca. 35,000 people).

Substantive theory focuses on the substance/subject of urban planning: e.g., on city form, design, layout, on what makes a good city, etc. (influenced by architecture, landscape architecture, geography, etc.). Procedural planning theory focuses on planning as a process (of decision-making, of community participation, of converting knowledge into action, of the challenges of plan implementation; etc.) You might consider the difference in how you read the phrase “urban planning” -- is your emphasis on the “urban” or the “planning”? This simple distinction is, like most dichotomies, not absolute, and many theories combine both procedural and substantive elements. That said, the procedural-substantive distinction can be a useful way to acknowledge the range of planning theories.

A small but influential group of writers, professionals, architects, activists, etc. who met (mostly in NYC) from ca. 1923 - 1933. Influenced by Geddes, E. Howard, etc. Stressed the dangers of over-concentration in central cities and advocated instead for a regional balance between city and countryside (e.g., through garden cities). See question #2 above. See also Peter Hall’s chapter “The City in the Region” in Cities of Tomorrow.

interesting question. The “common good” is not a term we have really used in this class, and it seems to have various meanings in different contexts, often referring to an interest or benefit broadly shared by the public. (Perhaps some might find overlap between the “common good” and the “public interest”.) In planning, we talk about “public goods” in explicit reference to economics. Public goods (in contrast to private goods) have two characteristics -- non-rivalry and non-excludability -- that lead to the private sector under-producing such goods (such as national defense, public safety, education, etc.). Therefore the public sector steps in and partly or completely provides these goods (They might directly produce them, or instead subsidize either the production or consumption of these goods. Think of government-built public housing vs. government tax-subsidies of private affordable housing units vs. rent assistance payments to the poor.) (The valuation of these goods is therefore partly or completely determined not by market demand, but by the political process: whom we elect, how we vote on bond issues, etc.)

I think you are referring to the (interesting but challenging) article by Heather Campbell and Robert Marshall ("Utilitarianism’s Bad Breath? A Re-evaluation of the Public Interest Justification for Planning.”) They make the distinction between consequentialist (focusing on consequences, outcomes) and deontological (rule-bound, procedural) versions of the public interest. The authors then examine how the recent emphasis on communicative action (CA) fits into this debate about the public interest. The authors are supportive of CA but also see its limitations: they do welcome communicative action’s “emphasis on difference, diversity and democracy, has made a positive contribution to the debate about the future of the planning enterprise.” But they worry that CA alone won’t necessarily lead to good substantive outcomes: “An open agenda for public deliberation seems unlikely to provide the means by which important collective values can be upheld and maintained. To paraphrase Pitkin (1981), no account of planning, politics and the public can be of value if it is empty of all substantive content, of what is at stake.”

in simple terms, it is the two-way interaction between society and space (i.e., place, geography, cities). A dialectic is the tension/juxtaposition/interaction between two forces, ideas, etc. This is simply a conceptual description of what we constantly observe and discuss (and often implicitly assume) in planning and design: that social forces shape the way that buildings and cities are constructed, and that the built environment in turn influences society. (Of course, we can get into lively -- and perhaps unresolvable -- debates about which force is stronger: society → space or space → society …). Let’s conclude with the Winston Churchill quote: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

a good question with a potentially long answer (I’ll aim for a short one). Both the property contradiction (PC) and market failure (MF) are useful concepts in the larger debate over the justifications for government intervention into the private marketplace. Each provides an economic framework to argue for the necessity for government intervention into the economy -- and by extension, for planning intervention. One difference may be in the nature of the relationship between the public and private. In the MF model, the public sector might be seen as a “corrective” of the shortcomings of the market (as if one is adjusting a flawed machine). In the PC view, there is this built-in tension (contradiction, conflict) between the public and private sectors that can create a combative, if not unstable, push-pull between the two.

MF is a concept borrowed from micro-economics. Beginning with the premise that a market functions optimally if certain assumptions are met (competitiveness, perfect information, no externalities, etc.), what happens when some of these pre-conditions are NOT present? The market does not produce a socially optimal amount and type of goods or services at the socially optimal price. We call this a market “failure” (or you could call it a market suboptimality, or flaw, since the market doesn’t necessarily completely “fail”). How to fix this market failure? There are numerous government strategies: government production of the good or service; government subsidies (to encourage private production), price controls, tax policies and other regulations, etc. (Planners, of course, often use zoning and other land use regulations.) Does the presence of a “market failure” necessarily mean that government intervention would be better? Not necessarily, since government intervention might have its own set of negative consequences (often called a “government failure” or “non-market failure”).

The PC describes the tension (i.e., contradiction, conflict) between the role of property (e.g., land, housing, etc.) as a private commodity vs. its role as a social good/need. In a way, such property has both public and private characteristics (at least in our current political economy), and therefore the tension between the public and private -- and the resulting arguments for and against public sector planning -- is built into the system itself.

** for a discussion of the property contradiction, see Question #14 above.

(Note: I am not an economic historian, but you might trace the differences back to the two ideas’ origins: MF in micro-economics, and PC in the economic thinking of Proudhon, Marx and the tensions between “exchange value” and “use value.”)

Big question, but I’ll provide a few key points and observations. (It’s interesting, by the way, that we rarely strive for a consensus view of urban planning, but from regional planning we more readily offer a summary definition.)

- Regional planning advocates typically define the region (and assert the importance of the region) in contrast to the city/municipality. The city is too small a scale, too fragmented, to deal with the urban areas as a complete system. The region best describes and contains the functional urban system and its parts: housing markets, labor markets, transportation networks, water and other resources, etc. And the regional scale might allow city-suburb inequities to be more directly addressed (e.g., between Detroit and its suburbs) -- though this city-suburb inequality understandably also leads many communities to resist greater regional efforts. Localism is a powerful force.

- I hesitate to provide a tidy categorization of the eras of American regional planning, but there is an early 20th century era of regional planning (both the “metropolitan planning” of the Regional Plan Association and its director Thomas Adams and the “regional planning” of the RPAA with Mumford, Wright, Stein, Bauer, MacKaye, etc.) with its emphasis on regional balance (of city and countryside), influenced by Geddes and Howard, etc.; then morphing/changing into the regional development efforts of the 1930s New Deal (TVA, Resettlement Administration, National Resources Planning Board, etc.) with an emphasis on regional economic development to counteract the poverty and underdevelopment of the Great Depression; then all that shifting into wartime mobilization of regional and national resources (1941-45); then a postwar period of pent-up consumer demand driving the mass construction of suburban housing, auto consumption and highway building (where the pre-1945 emphasis on regional, territorial planning gave way to a new faith that industrial and commercial growth would, through the rising middle class, auto-mobility, new roads, rural electrification, etc., lead to a convergence and integration of the nation -- and thus no longer a great need for pre-war type regional development planning); then a 1970s era push for regional planning through municipal consolidation, etc., all shaped by both the concerns about the “urban crisis”, white flight to the suburbs, and the growing environmental movement. And in the current era (what some might call “new regionalism”, which is a rather imprecise term meaning many things, but loosely describes the shift from ca. the 1970s to today)? a mix of many things: regional planning through collaboration (rather than consolidation); a focus on transit to link the region; on sustainability; on the impact of the “technoburbs” (new regional employment centers outside the central city); on a polycentric region (rather than the old regional model as single central city-suburbs-rural hinterland); megaregions; etc.

[more broadly speaking, the US has had a complex, long history of both implicit and explicit regional development efforts through Congressional action, Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers, the westward expansion and “Manifest Destiny”, using military spending as an implicit regional development policy, National Forest service and other government land policies; etc. But that is a bigger history than the more narrowly defined history of 20th and 21st century regional planning…] - What has triggered this recent shift in regional thinking? changes in the spatial structure of regions themselves; changes in the economic structure of regions (especially the shift from manufacturing to more services and high-tech); changing fiscal policies and threats in local and county finance; ISTEA and the rise of MPOs; global competition; etc.

- In a way, the evolution of regional planning thinking is similar to the evolution of urban planning thinking, but with the added emphasis on changing city-suburb relations; the inherent inter-governmental complexities; the dramatic geographic expansion of the region; and the persistent dilemma (at least in the US) that though regional-scale planning might seem increasingly urgent, the country has a weaker tradition (and legal institutions) of regional planning than many other countries.

- to review, see Peter Hall’s chapter on regionalism, and Fishman’s "The Death and Life of American Regional Planning." chapter in Reflections on Regionalism

- NOTE: this is likely far more detail than I would expect you to know for the exam (since we only spent one session on regional planning), but it is useful to know a few basic ideas/concepts, such as that distinction between Adam’s metropolitan planning (RPA) and Mumford’s “regional” planning (RPAA); a few basic ideas about how a region might be defined and what regional planning might offer that municipal planning does not; why the garden city idea might be appealing to regionalists such as Mumford; etc.

New (often relocated) capitals intrigue planners because (among other reasons) these projects give architects and planners a rare chance to not only built an entire new city, but given its status as national capital, there is typically a big budget and the opportunity (and compulsion) to make a powerful symbolic statement through design. A few other points:

- there are many (overlapping) reasons why a government might move its national capital: to symbolize a new start/a new regime (e.g., the move from St. Petersburg to Moscow); to counteract the over-concentration of population, power and economic activity in the historic capital city (from Rio to Brasilia); to trigger development in a new region of the country; etc.

- In the case of Brasilia and Chandigarh, these new capitals came during the height of the Modernist movement, so their respective governments used Modernist architecture to present their government seats as new, efficient, rational, modern. (This also led to subsequent critiques of these capitals as being either isolated, out-of-touch with the local population and/or not in keeping with the local environment. These are valid criticisms, but at times Brasilia and Chandigarh also became scapegoats in an anti-Modernist polemic.)

(Peter Hall discussed new capitals in his book.)

(Yes, we didn’t really cover this movement in class -- Robert Fishman teaches a great course in the winter semester that would cover all of this: UP 594 - Amer Pln 1900-2000)

The standard planning history contrasts the City Beautiful Movement (ca. 1890s - 1910s) and its emphasis on civic buildings, parks, etc. with the City Efficient (aka “City Functional”) Movement (hard to date, but maybe roots in the late 1800s through the 1920s?, though its legacy lives on). To quote Buenker (from below -- in ctools but not assigned this semester): “The City Efficient Movement was the product of a marriage between two of the most significant phenomena of the Progressive Era: the municipal reform movement and what has been dubbed the ‘efficiency craze.’” That is: a combination of efforts to clean up city government and to run government based on principles of rational efficiency (ideas heavily discussed at the time in an era of rapid industrialization and the development of new, “scientific” ways to organize production). Cities established offices to promote efficient municipal government. A young Robert Moses worked at such an office (The New York Bureau of Municipal Research) in ca. 1913-14.

A quote from Mel Scott’s standard history of planning:

“The emphasis on the City Efficient or the City Functional characterizing the city planning movement by 1912 was in some ways a logical out-growth of the social impulses that had crept into the City Beautiful movement as it became concerned with playgrounds. transportation. and terminals.” Scott, M. (1969). American City Planning Since 1890. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 123

resources: Buenker, John D. 2007. "City Efficient Movement" (Encyclopedia of American Urban History) [in the ctools resources folder]

City Beautiful and City Efficient movements. Encyclopedia of American Environmental History, vol. 1.

Could you please distill the major ideas of communicative action planning? And its connection and distinction with advocacy planning?

THE BIG QUESTION here is: How can we promote a more democratic and inclusive form of planning (the latter leading to the former?)

- Collaborative planning = communicative planning (sometimes also argumentative planning, planning through debate, inclusionary discourse, etc.)

- a dominant debate in PT since the 1990s

- A reaction to what was seen as either exclusive, elitist, top-down planning or else the ineffectiveness of planning

- a recognition that what planners mostly do involves communication (deliberation, facilitation, mediation, etc.) rather than the technical development of formal plans.

- And linked to the critique of modernism and the rise of “postmodernism”

- A focus on diversity, inclusiveness, language (since the range of interests gets reflected in a range of voices) --

- one also sees here an echo of Davidoff, though he seemed to be more literal in his view of advocacy – people know their interests, but do not have voice/power. And he seemed to think more of pluralism, rather than the collective construction of an ideal speech situation.

- Forester calls this practice: “inclusive deliberative practices”

- Note: deliberation has two related meanings:

- To weigh in the mind; to consider carefully with a view to decision; to think over.

- Of a body of persons: To take counsel together, considering and examining the reasons for and against a proposal or course of action.

- Here is a useful table to compare communicative action (vs. an older model of rational, technocratic planning):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I included this pair of terms to help differentiate between two claims about the advantages of cities: are cities economically successful because they are efficient (due to scale economies, making the same goods and services at lower per-unit costs)? or because they have higher levels of innovation (i.e., developing new goods and services, or new ways to produce such goods and services)? Both are present in cities, but much of the recent literature (see, for example, Glaeser, or some of the ideas cited in Lehmann) emphasizes that the recent vibrancy of cities is likely due to their clustering of innovative activities. One might argue that if a city only relied on efficiencies to gain advantage over suburbs and rural areas, that the diseconomies of scale (e.g., congestion, higher costs of living and working in big cities) would overwhelm much of the economies of scale in cities. Therefore it is the added advantage of being innovative that gives cities its greater advantage over other places. (Jane Jacobs would make arguments that sound similar). [Note: you might see some similarities between the efficiency-innovation and growth-development dualisms.]

A good discussion of this is in Dalton, L. (1986). Why the Rational Paradigm Persists: The Resistance of Professional Education and Practice to Alternative Forms of Planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 5(3), 147-153. [in ctools, though not assigned in class]”

“Typically planners use a model of choice from utility theory as symbolic of the rational paradigm in planning. Banfield (1959) characterizes planning as a rational process of selecting the best means to achieve some pre-determined ends - a way of choosing the "correct" answer based on an assessment of the consequences of alternative solutions. Consistent with its origin in economics, the notion of efficiency is inherent in this decision making process. Rational choice then depends upon people's ability to know and measure their preferences (utilities), consistency, and continuity among these preferences; complete knowledge of the choices available and their consequences; and the ability to determine the uncertainty and risk involved in a decision (Harsanyi 1982; Sen and Williams 1982).”

Often we interchange rational planning and comprehensive planning as two overlapping ideas. And that then leads to the criticisms/alternatives to the rational/comprehensive approach: incremental, advocacy, strategic, equity, communicative, etc. (You could include Rittel and Webber’s “wicked problems” in this questioning of the rational planning model.)

The trick here is that many planning theorists have beaten up on rational planning (just as many have beaten up on modernism, technology, science, etc.), but either (a) seem to construct a strawman image of rationality (so it’s easier to knock it down); or (b) don’t provide a compelling alternative to the rational model.

An interesting, big question with no simple answer. A short answer might be yes: planning’s common view of modernism and technocracy are similar and overlap. Technocracy focuses more specifically on the methods or structure of governing or managing (e.g., managing systems, cities, institutions, etc.). (from the OED: “Government or control by an elite of technical experts; (also) a doctrine or theory advocating this.”) Modernism is a broader idea, often referring to movements (in planning, architecture, art, literature, etc.) with numerous (sometimes conflicting) characteristics. Some might view the technocratic planner as embedded in -- or emerging from -- the larger modernist spirit of planning, design and governance.

Yes. Especially for planners (who likely have a more simplistic -- and often negative -- view of Corbu than architects), he is often the epitome of high modernism. See Peter Hall’s critical views of Corbu, or the anthropologist James Scott ("Authoritarian High Modernism") -- both readings from class. See also Jane Jacobs’ withering attack on Corbusier.

It depends whom you ask (and whether you are defining modernism narrowly or broadly, such as an art movement, an architectural style, a mode of city planning, or a larger logic of social organization and thinking dating back to the Enlightenment)! Several competing answers:

a. It ended with the rise of post-modernism in the 1970s and 1980s. (Charles Jencks viewed the 1972-73 demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe public housing towers as "the death of Modern architecture." [link])

b. It never ended, but simply morphed: we are in a period of late modernism, neo-modernism, etc. Post-modernists exaggerated both the sins of modernism and the finality of its death.

c. We are in this in-between period of modernism and what comes after (a hybrid of a and b)

d. "We have never been modern." to quote the title of Bruno Latour's 1991 book (original French title: Nous n'avons jamais été modernes).

e. One can date the start and end of life forms, institutions, buildings, even cities. But Modernism is such a sweeping, complex category that putting start and end dates is an exercise in futility.

The practice of living in high-density, multi-story buildings long predates Corbusier, though he is well known as being a prominent advocate of rebuilding whole city neighborhoods with Modernist apartment towers (e.g., his unbuilt 1925 "Plan Voisin" for Paris). The ancient Romans, for example, built insulae [link]

The invention of the modern elevator in the mid 1800s mitigated one of the primary drawbacks of living and working in multistory buildings. [link] [link]

[This New York Times multimedia site has a wonderful video (narrated by Feist) on “A Short History of the Highrise” (well worth watching).]

Take a look at the list of names at the beginning of this page. I would focus on those that we (a) read in class and (b) discussed in class.

“Hinterland (OED) Etymology: < German hinterland, < hinter- behind + land land. 1. The district behind that lying along the coast (or along the shore of a river); the ‘back country’. Also applied spec. to the area lying behind a port, and to the fringe areas of a town or city.”

This somewhat broad, imprecise term simply refers to land that is behind or outside, e.g., outside a city. It’s not commonly used in contemporary planning theory, though it can be useful (when you want a term with a meaning somewhat different than either suburb or rural or wilderness). I included it in the list of land types, but it’s not one to worry about...

Rexford G. Tugwell (1891-1979). PhD Penn (econ) 1922.

We haven’t talked much about Tugwell in class, but he led a fascinating life and was a prominent figure in mid-20th century planning. He was a member of FDR’s so-called “Brain Trust.” In 1935 Roosevelt appointed him head of the Resettlement Administration, which built several greenbelt communities (such as Greenbelt, Maryland). Tugwell was chair of the New York City Planning Commission between 1938 and 1940, where he clashed with Robert Moses (e.g., Tugwell advocated for a Master Plan for the city, which Moses opposed).

Roosevelt appointed Tugwell governor of Puerto Rico (1942-46). In 1946 Tugwell went to the University of Chicago, where he helped establish a new academic program in planning (a highly influential planning program that emphasized policy and economics, rather than planning’s traditional orientation towards architecture). He remained there from 1946 to 1957, before moving west to UCSB. [link] [link] You might contrast Tugwell’s view of centralized planning with Friedrich Hayek’s. [link]

Short answer: both. It’s a broad term, that applies at many scales and units of analysis.

The “division of labor” refers to the way that tasks are divided – e.g., among workers, firms, locations, etc. The spatial scale of these divisions can be small (e.g., tasks done in different locations of the same factory), or within a city, a region, nation, or globally. (An obvious example: Apple may design the iPhone in California, but have it produced in Asia. See. http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/228315 [see also this clip from Robert Reich’s film, on where iphone profits go by country.]

The push towards reducing costs often leads to the division of labor. Some tasks can more easily be “outsourced” (e.g., standardized work such as manufacturing basic metal parts) than others (e.g.., non-standardized work requiring close proximity to markets). A New York bank may put its “front office” work in an expensive office in Manhattan, but relocate its “back office” work (e.g., check processing) outside the city to save money.

We discussed nodes in the session on regions and regional planning. A core question of regionalism is: how do we draw the boundaries of regions? A traditional typology of regional types is: nodal (the region is the area surrounding a central place/node and functionally linked to that central place – e.g., as a labor market). Homogenous (the region is an area that shares common characteristics: e.g., language, dialect, ecology, etc.), and political (the region defined by existing political boundaries). These are ideal types, and useful analytical concepts in defining regions.

A big, contested question. Simple answer: post-modernism was/is a movement (starting in ca. the 1970s) as a reaction to modernism. Various disciplines had their own (overlapping) versions of postmodernism: art, architecture, literature, planning, etc. Because it was/is a complex, broad and imprecise term, it’s hard to say exactly when it started, if it has ended, and how big its impact has been. For many, it came as a powerful, welcome, even liberating corrective to the sins of modernism. For others, postmodernism was more of a temporary, transitional movement (or even a fad) that lacked a sufficient agenda to represent a viable alternative to modernism.

Postmodernism represented an alternative (to the modernist) way to…

view the city (aesthetics)

design the city (architecture/urban design)

envision community (the politics of difference and diversity)

structure the process of city planning (decision-making through collaboration, multiple voices of participation, away from the “master” plan)

Modernist plans: to be made and followed. (theory: to understand causality)

Post-Modernist plans: to be rewritten and interpreted -- or even to be rejected altogether as the modernist “master narrative”. (theory: to understand meaning)

Keywords of postmodernism: double-coding, multiple levels, multiple voices, Dualisms, Irony, paradox, juxtaposition, Simulacrum, Authenticity and imitation, Simultaneous (not linear, sequential), Beyond linear view of technical-rational progress, Diversity, Inclusive, pluralistic, City as spectacle/as theater, Time and space compression, Fragmentation, Shift from production to consumption.

see some of the readings from the session on Modernism.

an interesting reading/reflection on postmodernism:

Hari Kunzru. 2011. Postmodernism: from the cutting edge to the museum. The Guardian. 15 September.

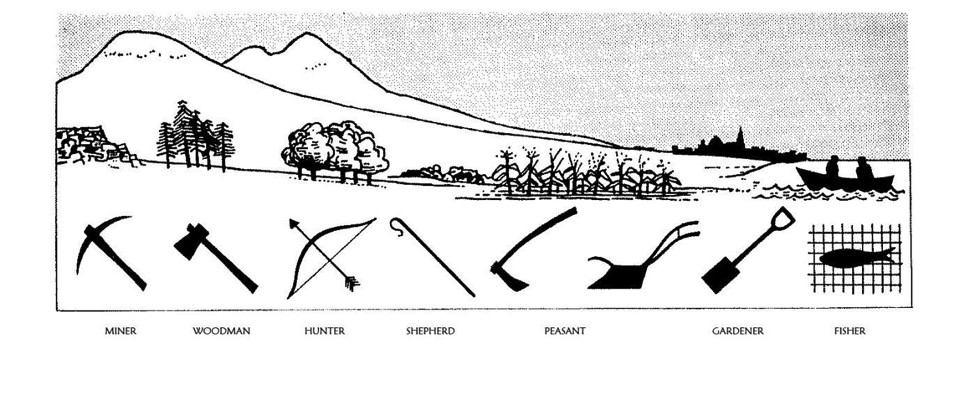

Geddes (1854 - 1932) was a Scottish town planner with broad, eclectic interests in biology and other fields. A foundational thinker in regional planning, who heavily influenced the American Lewis Mumford (see Peter Hall’s chapter in Cities of Tomorrow). see also: NLS site on Geddes.

an illustration of Geddes’ “valley section”:

Stein (1882 –1975) was an American architect and planner, best known for his 1920s collaboration with Henry Wright on the innovative Sunnyside Gardens (in Queens, New York City) and on the garden city of Radburn, New Jersey. A member (with Wright, Mumford, MacKaye, Bauer, etc.) of the small but influential Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA).(For a discussion on the RPAA, see the chapter on regional planning in Peter Hall's Cities of Tomorrow.)

source: http://tclf.org/pioneer/clarence-stein

The TVA (1933 - ) is a huge federally owned corporation, created by the new Roosevelt Administration in the first 100 days of his administration in 1933. It quickly engaged a massive project of hydroelectric dam building, flood control, navigation and irrigation and new town building along the Tennessee River. The TVA became a powerful symbol of both the New Deal and of regional development planning. Its programs (including rural electrification) aimed to address the rural poverty and underdevelopment of the region. see: http://www.tva.com/abouttva/history.htm

It depends on whom you ask. For urban economics, bifurcation usually refers to the “bifurcation” or splitting of the labor market into two increasingly separate groups: high-end, well-paid jobs for well-educated (and well-connected), and low-end, poorly-paid jobs (often with little or no benefits). In between these two distinct groups is a middle that may be disappearing/shrinking. (Traditionally, manufacturing jobs represented a big part of this middle.) Saskia Sassen and other global city theorists observe this bifurcation in global financial centers such as New York City. Scholars often examine the growing bifurcation of the labor market to understand the growing inequality in the U.S.

Yes, he does not challenge the importance of planning per se, but rather explores the ideal scale and location of planning. Planning is decision-making, which in turn requires information for good, timely decision-making. So the question is: how do you bring the information and the decision-makers together? For Hayek, centralized planning is inefficient in this process: the price system (as a decentralized system) is a far more capable mechanism for communicating information. These two paragraphs are key:

“In ordinary language we describe by the word "planning" the complex of interrelated decisions about the allocation of our available resources. All economic activity is in this sense planning; and in any society in which many people collaborate, this planning, whoever does it, will in some measure have to be based on knowledge which, in the first instance, is not given to the planner but to somebody else, which somehow will have to be conveyed to the planner. The various ways in which the knowledge on which people base their plans is communicated to them is the crucial problem for any theory explaining the economic process, and the problem of what is the best way of utilizing knowledge initially dispersed among all the people is at least one of the main problems of economic policy-or of designing an efficient economic system.

The answer to this question is closely connected with that other question which arises here, that of who is to do the ;planning. It is about this question that all the dispute about "economic planning" centers. This is not a dispute about whether planning is to be done or not. It is a dispute as to whether planning is to be done centrally, by one authority for the whole economic system, or is to be divided among many individuals. Planning in the specific sense in which the term is used in contemporary controversy necessarily means central planning--direction of the whole economic system according to one unified plan. Competition, on the other hand, means decentralized planning by many separate persons. The halfway house between the two, about which many people talk but which few like when they see it, is the delegation of planning to organized industries, or, in other words, monopolies.”

source: Friedrich Hayek, 1945. The Use of Knowledge in Society. American Economic Review, XXXV, No. 4; September, 519-30. [link]

I think you are referring to the writings of the late political scientist Iris Marion Young (1949 - 2006). Young sees these two terms as not the same, since there is a difference between structural and cultural group differences. Young argues that critics have wrongly reduced the politics of difference to “identity politics” (i.e., the expression of cultural meaning). Young recognizes that identity politics (in which marginalized groups assert alternative, positive group images) have their legitimate role. However, her primary focus is on the structural foundations of the politics of difference. The assertion of group identity is not usually a stand-alone cultural goal, but instead is usually linked to group demands for substantive, structural outcomes: access to better education, housing, work opportunities, social services, etc.

Here is a useful quote on the politics of difference:

“The ideal of community … expresses a desire for the fusion of subjects with one another which in practice operates to exclude those with whom the group does not identify. The ideal of community denies and represses social difference, the fact that the polity cannot be thought of as a unity in which all participants share a common experience and common values. In its privileging of face-to-face relations, moreover, the ideal of community denies difference in the form of the temporal and spatial distancing that characterizes social process. … As an alternative to the ideal of community, I develop an ideal of city life as a vision of social relations affirming group difference. … As a normative ideal, city life instantiates social relations of difference without exclusion. Different groups dwell in the city alongside one another, of necessity interacting in city spaces ...[D]ifferent groups … dwell together in the city without forming a community.” Young, Iris Marion. 1990. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (Chapter 8: "City Life and Difference", p. 341).

Fascinating question. I can see why one would think so, since she was such a strong critic of many elements of modernist architecture and urban design -- and because there seem to be many parallels between her vision of cities (provide a mix of old and new buildings; return to smaller, pedestrian-friendly streets; listen to the citizens rather than simply defer to technocratic experts, etc.). But would Jacobs have called herself a postmodernist? I don’t know (I can’t find any direct quotes from her), and my guess is that she would have bristled at such a label.

Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs might represent two divergent variations or impulses of the modern age. You can pick up on this theme in Marshall Berman’s description of Jacobs:

“If there is one work that perfectly expresses the modernism of the street in the 1960s, it is Jane Jacobs’ remarkable book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. … I believe that her book played a crucial role in the development of modernism: its message was that much of the meaning for which modern men and women were desperately searching in fact lay surprisingly close to home, close to the surface and immediacy of their lives: its was all right there, if we could only learn to dig.” [Berman, Marshall. 1988. All That is Solid Melts into Air. New York: Penguin: 314-15]

I can see why technoburb and edge city sound similar. They both are relatively recent terms to describe new forms of development on the edge of the metropolis. I think the key difference is the land use mix: Fishman developed the term “technoburb” to describe a new form of suburb that contained not just traditional suburban housing, but also employment centers (and given the high-tech focus of many of these new suburban employment centers, he called them technoburbs). The Washington Post journalist Joel Garreau developed the idea of the “edge city” in 1991 (Garreau, J. (1991). Edge city: life on the new frontier. New York: Doubleday). These were relatively new developments, built on greenfield sites, with a concentration of commercial and retail space (with less emphasis on residential). Examples: Tysons Corner (in Northern Virginia, part of the greater Washington DC region, is a famous example).

Tysons Corner, VA. source: http://lewishistoricalsociety.com/wiki2011/tiki-read_article.php?articleId=98

Megalopolis was a term coined by the geographer Jean Gottmann (Gottmann, J. (1961). Megalopolis: The Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the United States. New York: The Twentieth Century Fund.) to describe the interconnected, overlapping metropolitan areas from Boston to Washington. (We now think of this as the largest of the “megaregions” in the US).

A megacity is simply defined as an urban agglomeration with a population of 10 million people or more.

This is a simple distinction to describe a complex differentiation of different types of suburbs. In literal terms, the inner-ring suburbs (or inner suburbs, or first ring suburbs) are those in the first ring outside the central city. They tend to be older and more dense than the newer suburbs further away from the central city (e.g., outer-ring suburbs). That said, there can be very wide variations in these suburbs: some may be prosperous, taking advantage of proximity to the central city, good transit and a lovely, pre World War Two housing stock. But other inner ring suburbs may be struggling working class suburbs that can’t compete with the stronger housing stock further out. So, these are useful terms to help us differentiate between the wide array of suburban forms, but they don’t have a precise land use, legal or political meaning.

Useful resource: http://www.planetizen.com/taxonomy/term/280

Good question! The simple answer is that “radiant city” is the English translation of “Ville Radieuse”. I can speculate (about how the tower in the park design would allow for light and activity to radiate through the city...), but I have not yet found an exact, accurate answer.

Another good question. Popularity can be measured by (a) what planners, architects and critics think or (b) what people demand in the housing market. There have certainly been many critics of New Urbanism, but also many supporters. There are formal examples of new urbanist developments (Seaside, FL; Orenco Station, OR; etc), but perhaps the bigger influence has been on how it has shaped a much larger number of otherwise conventional developments (e.g., encouraging mixed-use, street-level shopping and cafes, walking and transit, orientation to the street, etc.). One power of New Urbanism is that it makes planning ideas visible, concrete, easily experienced and graphically expressed. (This cannot as easily be said about communicative action, advocacy planning, etc.).

I was recently in Austin, Texas and toured the new urbanist-style Mueller development (on an old airport site). It’s an impressive place, and the residents seem to like it. (And studies by planners at UT Austin seem to be upbeat.)

There are a wide range of new urbanist-like developments. Some are greenfield sites far from the city center (which is a source of criticism); others are closer to the city, linked well with transit, or actually urban infill projects.

Some criticism seems to just be aimed at the more kitsch, tacky design features that strike some as too nostalgic, Disney-like, etc. I’ll let you judge whether those are fair or unfair criticisms. Others criticize what is perceive to be the middle and upper-middle class orientation to many of these projects. But again, there is a wide range of price levels for new urbanist projects.

link: Congress of New Urbanism

In this context it is the assumption that the physical form of a city “determines” the social outcomes. Planning scholars tend to reject an overly mechanistic, deterministic relationship between the build environment and social outcomes (e.g. you can’t stop crime or make people happy simply by providing the right physical environment). But we tend to reject the opposite extreme: that the physical environment has no influence on you. We tend to be somewhere in the middle: the environment “shapes” (or partially determines, or influences) how we think and act, but it’s certainly not the only factor. [Example you might relate to: the Art & Architecture Building likely doesn’t determine your educational outcome and your social life and your emotional health; but neither can you say that the building has absolutely no effect on you…]

The Columbia University urban sociologist Herb Gans, in his 1962 book review of Jane Jacobs (The Death Life of Great American Cities), criticized Jacobs for making simplistic assumptions about how the physical characteristics of the city (density, street design, age of buildings, etc.) determines the social outcomes. Gans noted that Jacobs neglects all the other political, economic and social forces at work (including local politics, race, etc.). Let me quote from his thoughtful review:

“Her argument is built on three fundamental assumptions: that people desire diversity; that diversity is ultimately what makes cities live and that the lack of it makes them die; and that buildings, streets, and the planning principles on which they are based, shape human behavior. The first two of these assumptions are not entirely supported by the facts of the areas she describes. The last assumption, which she shares with the planners whom she attacks, might be called the physical fallacy, and it leads her to ignore the social, cultural, and economic factors that contribute to vitality or dullness. It also blinds her to less visible kinds of neighborhood vitality and to the true causes of the city's problems.” Gans, Herbert J. 1962. The Death Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs (Book Review). Commentary, Feb 1962; 33: 172.

Everything (just kidding…). That’s a big question. I would take a quick review of the regional planning session's reading: particularly Peter Hall’s chapter and Fishman’s article. A few basic questions:

a. how do we define regions? [e.g., nodal, homogeneous/unitary; and political; and beyond those categories: the traditional view of a metropolitan region is a city surrounded by its hinterland; but things get more complicated when metro areas have multiple central cities, and when multiple regions begin to blur together. We call those “megaregions”. Jean Gottmann called the Boston-Washington area “Megalopolis” -- see Question # 18 above.] There are also regions that lack an urban core, and in Europe, we see the term “region” used to refer to areas that cross national boundaries. “Region” is a widely used, and broad term.

b. why do planners advocate for regional-scale planning and coordination (and not just city-scale)? [sometimes for efficiency; sometimes for city/suburb/rural equity; sometimes to be more economically competitive; sometimes for environmental protection of regional scaled natural resources]

c. Why is regional planning relatively weak in the US? [a big, complicated question: think about the win-lose implications of city-suburb redistribution; or the “home rule” tradition in the US that often favors local over regional political power; or the lack of a strong federal program in regional development -- as compared to, say, Europe]

* see also Question #22 above.

Radburn (ca. 1929) is the best-known effort to implement Howard’s garden city model in the US. Not all of Howard’s original ideas from 1898 are included in Radburn: the community lacked an external greenbelt with agriculture, local industry and other aspects of Howard’s model of a broad array of land uses and activities and communal ownership. And the population remained far below Howard’s standard of 35,000 residents. What Radburn does have is lovely parkland internal to the development (which has nice pedestrian walkways), and efforts to separate car and foot traffic. It is a pleasurable place to stroll. The homes are arranged in a village-like pattern (not in a grid), and the clever design of streets and alleys demotes the dominance of the automobile. It has a calm feeling, with a sense of common order. Also: I appreciated the ability for kids to walk to school and the pool and park without crossing streets.

See Peter Hall’s chapter, “The City in the Garden” .

source: http://www.ppgplanners.com/development-and-preservation-strategies-radburn-fair-lawn-nj.html

See Question #4 (above) on Hayward. I would compare Hayward’s and Marcuse’s divergent views of political economy. Both seem to be critical of traditional environmental sustainability but for very different reasons. Hayward is critical of the environmentalists’ anti-growth, anti-progress rhetoric. Marcuse is critical of the way that sustainability policy might reinforce the status quo and therefore not address the way that sustainability might legitimate existing racial and class inequality.

Krumholz: the best-known advocate of “equity planning.”

Whyte (1917-1999): a remarkable journalist, urbanist, etc. Known to the general public as the author of The Organization Man (1956), but best known to urbanists as a thoughtful, articulate (and humorous) advocate of urban public spaces (especially in New York City), including his publication "The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces.” Every planner should watch his film (of the same name; link in the syllabus). Was also a mentor to Jane Jacobs.

I don’t know the specific details of the street design in Levittown. But developers/designers of postwar suburbs often built curvilinear street patterns that were intentionally NOT the grid that was associated with the older cities (that the suburban residents were leaving behind). Curves and cul-de-sacs suggested a country landscape (and traffic calming), with high-speed through traffic to be relocated to the edges of the community.

source: Tony Linck, Aerial View of Levittown, Life Magazine, June, 1948. [link]

The use of curvilinear streets in new suburban development has a longer history. For example, see this 1869 plan for Riverside, Illinois (designed by Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted). (Witold Rybczynski discusses the difference between pre-1945 and post-1945 suburbs in "Country Homes for City People"

source: http://chicagodetours.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/originalmap_500.jpeg

Interesting question. Though the distinction (often between procedural and substantive planning theory) can be useful, they might well just represent two ideal types that cannot exist in pure form (at least outside our imagination). If I had to describe their “pure” forms…. Substantive planning might focus exclusively on defining physical outcomes: e.g., theories about good city form, ideal densities, designs, etc. (without worrying about participation, decision-making etc.) Procedural planning might then focus on ways to organize information-gathering and decision-making processes as the primary focus of planning (regardless of the substantive merits of the outcome). So, can you have the one without the other? [You might imagine a division of labor within a large planning department, where some staff focus on substantive issues and other on process.]

Paradigm: “A conceptual or methodological model underlying the theories and practices of a science or discipline at a particular time; (hence) a generally accepted world view.” (OED 2nd)

Paradigm shift: “a conceptual or methodological change in the theory or practice of a particular science or discipline; (in extended sense) a major change in technology, outlook, etc.” (OED 2nd)

So a paradigm is a broad framework (and set of assumptions, beliefs, exemplars, etc.) that define and hold together a field (e.g., a scientific field) and its followers/practitioners/believers. Thomas Kuhn wrote the seminal modern text on the topic (Kuhn, T. S. 1962. The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.). (The shift from Aristotelian to Copernican views of the planets and universe is a frequent example of a paradigm shift.) Kuhn wrote about the natural sciences, but social scientists also embraced this idea to help explain how ideas and beliefs shift. When a scholar (or scholarly community) claims that there is a “paradigm shift,” that implies a major shift in the structure of values and thinking (not simply a marginal change in topic or method). Example: Innes, Judith. E. (1995). Planning Theory's Emerging Paradigm: Communicative Action and Interactive Practice. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 14(3), 183-189. Here Innes uses “paradigm” to signal what she sees as a major shift in the field (and/or a shift that she wants to happen). Yes, modernism and postmodernism have often been labeled as paradigms. Would City Beautiful also be a paradigm? That’s a tricky question, because it requires deciding what types of ideas or movements are “big enough” to constitute a paradigm.

Finally, given this view of paradigms, then yes, such major shifts in thinking and values might well include shifts in political views and values as well.

We briefly discussed this during the class on economic restructuring (this is not a methods class, so I won’t ask you to calculate a multiplier….).

The simple version: multiplier = TOTAL jobs / basic jobs, where total employment = basic employment (i.e., export-based) + non-basic employment (i.e., locally-serving). The multiplier is a simple ratio. How do you decide what is an export job? You first define the boundaries of the area of study (e.g., city, county, region, state, nation, etc.). If the source of revenue that pays for the job comes from outside this area, then we say that this job “exports” its products (either goods or services) outside the area.

To review the example we used in class: a small Pacific Northwest timber community exports wood products (and nothing else). If 200 people worked in the lumber/timber sector, and 400 other people worked in (non-export) sectors (e.g., cafes, schools, hardware store, etc.), then the multiplier is 600 / 200 = 3.0

Lewis Mumford (1895 – 1990). For several generations of urbanists and planners, Mumford was arguably the giant of the field. An architectural critic, urbanist, social thinker, advocate for regional planning, etc., some called Mumford the last great Humanist (or the last Renaissance Man). His book, The City in History, is a classic. (He wrote well over 20 books.) See also Q2 and Q7 above. Brought the ideas of Patrick Geddes to the US. A key member of the Regional Planning Association of America. Advocate for “regional balance” and for garden cities. An early writer on the connections between cities, technology and society. Take Prof. Fishman’s class in the winter and learn more about Mumford. And here is Mumford's obituary in the New York Times.

Note: we read his article “What is a City”

Interesting observations. Re the first part: If planning wasn’t a formally established profession until about the 1920s, then the early pioneers came from other disciplines (architecture, engineering, political activism, sociology, economics, law, etc.). Even since the 1920s, many have come from other disciplines: planner is a field with permeable boundaries, and many others come to planning from other fields. Re the second and third parts: those are fascinating questions, but we will save them for another time…

A thoughtful, important question: where does planning look for its history, for its prototypes, for inspiration, for comparison? The history of cities is thousands of years old, but yes, we tend to start our history of modern town planning with the industrial revolution -- and not even the early days of industrialization, but the later period (starting at the end of the 19th century). This may be particularly an American phenomenon, this narrow view of history. Perhaps Americans have less patience with history, and our pragmatic streak tends to focus on the “here and now.” So you identify two restrictions here: a temporal (we focus on the last 100+ years) and a spatial (a US/UK, western Europe orientation). This seems to be changing, but slowly. More planners talk about “globalizing the curriculum.” Perhaps another reason to organize an “expanded, expanded horizon trip” to Asia in a future year?

That’s a big question! Every field needs foundational stories/origin stories, and the Chicago of Burnham and the Fair and the Plan is a big one for planning. See these as early, high-profile prototypes that would shape planning and city building in years to come. Or see how the tensions and contradictions in Burnham’s Chicago would reappear time and again in planning efforts to this day (e.g., private planning for the public sector; the power and limitations of using urban form to promote social reform and order; the tensions between elites and the masses; the power of boosterism and growth machines in getting projects built; the power of a “plan”; the early marketing of place through big events such as the fair; etc.)

I would revisit William H. Wilson, in "The Glory, Destruction, and Meaning of the City Beautiful Movement,” (from his book, The City Beautiful Movement), who both acknowledges the criticisms of this movement, but sees a positive legacy: congestion-reducing road design; parks and landscaping; innovation of the planning commission; and a new culture of urban reform.

A few quotes from Wilson:

“Burnham and Bennett's magnificent Plan of Chicago (1909) symbolized the maturation of the City Beautiful. Analyses of the plan accept the symbolism and divide its proposals into advanced elements looking forward to contemporary planning and atavistic schemes expressive of a City Beautiful already under attack when the plan appeared.” (p. 68).

“The limitations of the City Beautiful movement and of its critics aside, the movement achieved much. It spoke to yearnings for an ideal community (and to the potential for good in all citizens. Therein lies its most important but least remarked contribution. For all its idealistic rhetoric, the movement was imbued with the courage of practicality, for it undertook the most difficult task of all; to accept its urban human material where found, to take the city as it was, and to refashion both into something better. Contrast its realism with the contemporaneous antiurban Garden City movement, which proposed radical deconcentration and the destruction of the great cities. The Garden City movement and its heirs have thrilled academics with their altruistic systems involving significant restrictions on private ownership and enterprise. The fact is, however, that the Garden Cities and their successors have at best become suburbs with fairly typical suburban dynamics.

The City Beautiful movement was fundamentally an urban political reform movement. It left a legacy of civic activism and flexibility in the urban political structure. The professional planning expert advanced to the fore during the era, but the network of concerned, politically aware laymen was equally important to City Beautiful success.” (pp. 90-1)

Market failures are those instances where the economic market process fails to produce a good or service at a price and/or quantity that is judged to be optimal. Typical causes of market failures are the absence of one or more prerequisites to a well-functioning market: information, mobility, rationality, lots of buyers and sellers (a competitive situation), no externalities, etc. (Some might consider the term "failure" too strong, and instead speak of market "imperfections".)

MORE: market failures may not be the most compelling or theoretically interesting justification for public planning intervention. But it is an appealing framework for many, since it doesn’t rely overtly on normative or ethical arguments, but simply on the goal of ensuring economic efficiency. It is as if to say: “You don’t need to believe in social engineering or redistribution or social justice to support (this type of) planning. Support planning because it serves as a corrective to those instances where the market is imperfect and fails to perform optimally. This type of planning doesn’t challenge or replace the market, but instead enhances or fixes the market.”

My own understanding of the idea of market failure is that there is no consensus of whether the outcome economic inequality would be considered a “market failure”. [SC]

Now that’s a great, grand question! Partial answer: The answer depends on how you (or we, or government, or society) frame the aim of planning. Is it narrowly the technical and design-based creation and maintenance of the built environment? If so, then your three priorities are outside the portfolio of urban planning. But urban planners have often (but not always) defined their task more broadly, where this maintenance and design of the built environment is a means (or intermediary) to achieve other (social, economic, environmental, political) goals. (1) Can one make the case that sustainability, social justice and environmental justice (the latter can be seen as a combination of the first two) should NOT be intrinsic parts of planning education and planning theory? (2) Can one make the case that these three MUST be intrinsic parts of planning education and planning theory? I am not sure that one can answer these two questions conclusively using either theory or logical reasoning, since the answer is political and normative (and sometimes very personal). The Urban Planning Program has made an explicit commitment to putting these values at the forefront of its work and teaching. But each planner needs to construct their own definition and ideology of planning. [SC]

Now that’s a tough question! I would hope that planners can head this effort, or at least be amongst the leaders. Planners certainly have many of the requisite skills (ability to work across scales, disciplines, expertise; knowledge of social, economic and environmental systems; etc.) But we don’t automatically get a seat at the big table just because we have the skill set. We have to assert our place, our skills, and show that we bring something substantive and distinctive to the process: e.g., we are good at conflict resolution; we can find win-win solutions in the built environment; we can reduce traffic congestion and increase land values; etc. Having concrete, well-documented examples (of past planning work that was effective) that we can point to will help. In other words, how do planners demonstrate their value? (and thus why it is worth spending money to hire planners to get a better outcome?) [SC]