[Menu at Upper-Right ↗️]

Markus Nornes, a film scholar, programmer and maker, is Professor of Asian Cinema at the University of Michigan.

Markus Nornes is mainly known for his work in three fields: Japanese cinema, documentary, and film translation. He studied at Colorado State, UCLA, and St. Olaf College, attaining a PhD at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. He began teaching at Michigan’s Department of Film, Television and Media in 1996.

Nornes worked as one of the first programmers at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, and has been an active film curator for over 30 years. He was one of the founding members of the Kinema Club collective, which networks scholars and critics of Japanese media studies. He serves on the boards of various journals, and regularly sits on juries at international film festivals. He has organized over a dozen international conferences, and has delivered over 100 lectures the world over.

Biography

-

Beginnings

I was born in Minneapolis and grew up in Fort Collins, Colorado.

In junior high school, I used money from my paper route to buy my first camera, an Olympus OM-1. An avid mountain climber, I aspired to be a landscape photographer. My mother never understood and complained I never took pictures of people, but in high school I became the photographer for the school newspaper, Spilled Ink. But I was serious enough to write Ansel Adams and ask what he thought; he wrote back and told me to go for it.

However, around the same time, I fell in love with a girl who loved movies; I fell out of love with the girl, but she left me with a passion for foreign cinema. After two years of study at Colorado State University, I moved to Los Angeles to attend UCLA, supporting myself by working at the Mann National Theater in Westwood. Neither the big school or the big city suited me, so I returned to the Colorado to climb and photograph its 14,000 peaks.

Eventually, I went returned to study at St. Olaf College in Minnesota. I joined their Global study abroad program, which circumnavigated the planet. On every stop, I walked into random movie theaters to experience the scene.

Something clicked in East Asia, where I watched the first films of Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang in Taipei and Itami Juzo's The Funeral in Kyoto. This was a turning point in my life. I returned to Los Angeles to obtain a PhD at the University of Southern California. In 1996 he graduated, and my timing was excellent: I stepped into North America's first advertised position for Asian Cinema Studies.

-

Scholarship

I have written extensively on East Asian cinema, particularly its documentary traditions. I have also published on narrative cinema, translation, and film festival cultures.

My first book is Japanese Documentary Film (2003). It narrates the history of nonfiction film in Japan starting with actualities at the turn of the century. While I touch on all forms, I pay the most attention to political cinema of both the left and the right. One chapter introduces the Proletarian Film Movement of Japan (Prokino) in the late 1920s and 1930s. But most of the book presents an ideological and aesthetic analysis of the war cinema—including close textual analyses of war films subverted by their own makers, such as Fumio Kamei’s Fighting Soldiers (1938) and The Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1946). This research was an outgrowth of his first edited volume, The Japan-America Film Wars.

One of my other specializations is film translation, the subject of Cinema Babel: Translating Global Cinema (2007). I came to the topic after Sato Makoto asked me to subtitle his Living on the River Agano (1991). The God-like control I had over the film's meaning was humbling. At the very same time, I noted how few of the bibliographies for Japanese film books had Japanese sources; I realized how the scholarly field I aspired to enter was profoundly shaped by subtitlers and translators. This led me to write Cinema Babel, which offers a global history of film translation from the silent era to the present-day. The book fleshes out a theorization of subtitling and dubbing first laid out in a 1999 essay entitled, “For an Abusive Subtitling.” In these polemical works, I redefine fidelity to emphasize the materiality of language and critique domesticating translation methods especially typical of subtitling.

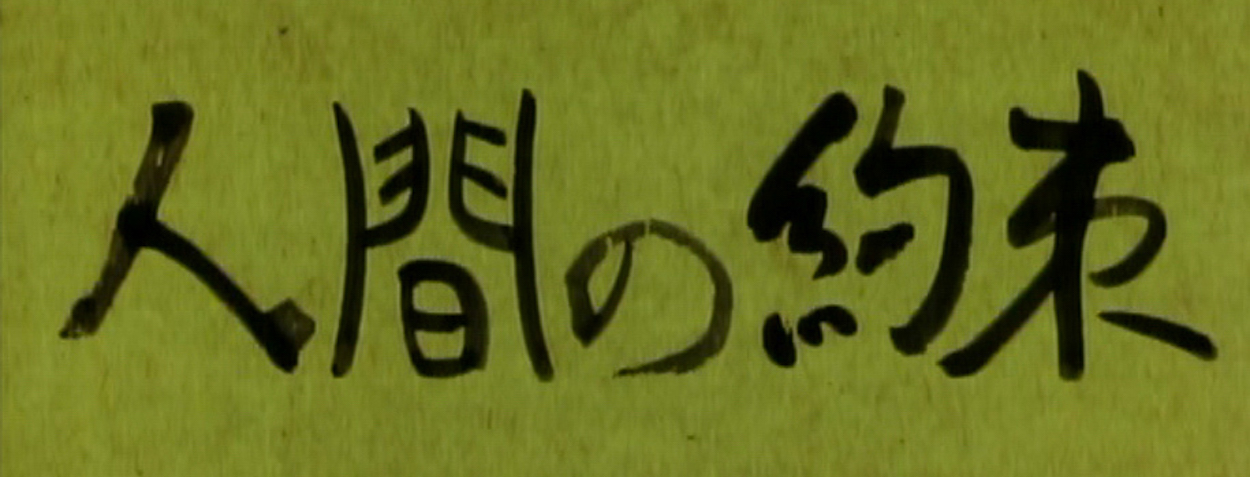

In 2021, I published Brushed in Light, an exploration of the intimate relationship between calligraphy and East Asian cinema. The open access book is accompanied by an image database of nearly 3,000 images from over a century of Asian film.

I have co-written two other books. Staging Memories: Hou Hsiao-hsien's City of Sadness, with Yeh Yueh-yu (2015), grew out of a digital humanities experiment from the early 1990s. It was the first hypertextual film analysis on the World Wide Web. A Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies (2009), co-written with A. A. Gerow, is a comprehensive, annotated bibliography of the resources undergirding the study of Japanese film. It also describes all the archives and libraries in the world with significant holdings.

My other edited books include The Pink Book: The Japanese Eroduction and its Contexts (2014), the first academic book to focus on the history of the soft-core porn industry of Japan. I also co-edited Hallyu 2.0: The Korean Wave in the Age of Social Media (2015) with Sangjoon Lee, as well as an 800-page reader of Japanese film theory entitled Nihon Senzen Eiga-ronshu—Eiga Riron no Saihakken [Rediscovering Classical Japanese Film Theory—An Anthology], which I co-edited with Iwamoto Kenji and A. A. Gerow. Finally, I also co-edited with Gerow a festschrift for our mentor, Makino Mamoru entitled, In Praise of Film Studies: Essays in Honor of Makino Mamoru (2001).

Aside from these works on paper, I have been active in digital humanities experiments from early on. Aside from the City of Sadness project, I edited an online reprint series of out-of-print books and archival materials relating to Japanese cinema. The books include foundational books from different periods such as Donald Richie’s Japanese Cinema: Film Style and National Character (1972), Noël Burch’s To the Distant Observer (1979), and David Bordwell’s Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (1982). The archival materials include a cache of documents from the production of The Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and most of the books and journals of Prokino.

- Curation

From my college days on, few things give me as much pleasure as bringing groups of people together for novel experiences of cinema. I have curated public exhibitions the world over—work I consider part and parcel with my scholarship. Programming is truly creative intellectual work. In recent years, I have also written about these experiences as film festival studies came into its own as an academic sub-field of film studies.

I began his career in exhibition at the National Theater in Westwood, Los Angeles in the early 1980s, where I rose from doorman to King Candy (!) to Assistant Manager. At St. Olaf I ran the film society, where he programmed his first film: Kurosawa Akira’s Seven Samurai. In the middle of my MA program in 1988, I served as an intern at the Hawai’i International Film Festival, where I discovered the pleasures and importance the international film festival circuit.

As a curator, I am best known for my co-programming of major retrospectives at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, starting with a Pearl Harbor 50th Anniversary event in 1991 entitled "Media Wars: Then and Now." This involved the collaboration of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration and the National Film Archive of Japan. I showed a scaled down version of this at the Pearl Harbor Memorial itself during HIFF. My other major programs at Yamagata were "In Our Own Eyes: First Nations’ Moving Images" (1993), "7 Spectres: Transfigurations in Electric Shadows" (1995) and "The Ethics Machine: Six Gazes of the Camera" (2013).

At University of Michigan, I have programmed yearly events since 1996. For example, in 2005 I programmed the first foreign appearance of Adachi Masao after his release from prison. Because Adachi could not legally leave Japan, he used what was then the new technology of Skype for a live, trans-Pacific discussion. In 2007 I programmed "X-Treme Private Documentary"; this was the first time Michael Moore met Hara Kazuo, who had a enormous impact on the Michigan filmmaker. When the Chinese independent film festival Yunfest was shut down, I invited the festival director to select a program of films to show in Ann Arbor, complete with visiting filmmakers.

I also organized year-long artistic residencies for documentary filmmaker Kazuhiro Soda and benshi Ichiro Kataoka. And I staged retrospectives featuring visits by artists Toshio Matsumoto, Harada Masato, Lee Myung-se, Jon Jost, Yoshida Kiju and Mariko Okada, Momoi Kaori, Hamaguchi Ryusuke, Alan Berliner, Cheng Pei-pei, Xu Bing, J.P. Sniadecki, Matsubayashi Yoju, Yuan Goangming, Cui Zi’en, Wang Wo, Ying Liang, Gordon Quinn, Wada Atsushi and others. A number of these events were programmed for the venerable Ann Arbor Film Festival

I have also collaborated on events in Asia and Europe on Wang Hongwei, Ogawa Productions, and served as juror on many international film festivals.

- Filmmaking

I started in Super-8 films in high school, and turned to various kinds of documentary after the turn of the century. I discovered the joys of documentary through ski porn when I was growing up, and when I began to watch foreign films I fell in love with the endless possibilities and powers of nonfiction.

Once in a while, I made my own. 9/11 (2002) is an experimental documentary produced six months after the World Trade Center attack. Inspired by Wendy Clarke’s Love Tapes, it is an experiment in freedom and control. Twenty-four college students sit, one-by-one, in front of a camera and a clock. They could choose a background image and music. And for exactly three minutes, each reveals their thoughts about 9/11.

In 2010, I made a feature-length documentary about small town America inspired by Ogawa Shinsuke's mountain films. It is entitled, Winger—47° 32’9”N 95° 59’14”W. Two old Norwegian farmers (my father and my uncle) stand amidst the ruins of their small town in northern Minnesota, sharing distant memories and local lore. There is nothing special about the town of Winger. But the film reveals a complex history embodied in the two old men, suggesting that every small town in America has an equally rich history.

I made The Player Played in 2017. A 5-screen installation based on the screenplay for the first shot of Robert Altman’s The Player. It explores the dynamic of spontaneity and planning in Altman's work, while revealing the rich productivity of the translations of his screenlay.

In 2018 I released The Big House, a collaboration with directors Kazuhiro Soda and Terri Sarris, and 13 of our students at Michigan. The film premiered at the Berlin Critics’ Week. It is a direct cinema style documentary on Michigan Stadium, showing everything but the game—from the cooks underneath the stadium to the snipers on the towers.

My most recent work is also a collaboration with students and filmmaker Chris McNamara, and is entitled When We’re Together (2020). An observational documentary, it covers the student activism surrounding the Michigan Primary and climaxes with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

- External Links

- Curation