| creatures

that resemble clams but are of a completely different nature.

Externally, each of a brachiopod’s two shells, when viewed straight on,

are symmetrical like the well-known heart-shape symbol, teardrop, or

spade symbols; clam shells are asymmetrical.

Except for the

two terebratulid brachiopods in Fig. 3, I personally recovered all

specimens seen here directly from well-known formations throughout the

U.S. and parts of Canada across 30 years time. These few specimens are

only the tip of the iceberg (i.e. it takes time to choose a few

specimens, scan them in, and compile the details; very difficult to do

when the brachiopod section alone could go on for many more pages). The

same treatment presented here for brachiopods will be provided for

other animal and plant groups as well and, hopefully, will demonstrate

the scope of the matter. I am providing the same information

evolutionists already have but with a different interpretation. And

again, make no mistake, this is all part of re-assessing the validity

of the evolutionary interpretation of human origins sold to the public

as scientific fact.

Darwin himself

knew quite well that the fossil record was problematic and was honest

enough to repeat this over and over again in The Origin of Species.

He clearly expressed—without rhetorical trickery—that the fossil record

did not support his theory; however, he believed that it must. Hence,

the beginning of the world’s first major science religion. Look at the

facts presented here and ask yourself, “Is evolution set-in-stone?”

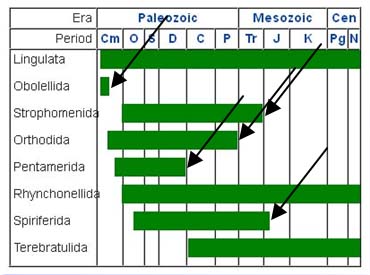

The date range details for each of the brachiopod genera are from Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database

which is housed at Macquarie University’s

Department of Biological Sciences, Sydney, Australia. The database is

assembled by hundreds of international paleontologists and is based on

the fact that the same fossils are present in formations around the

world.

In last issue’s Tales of a Fossil Collector, Part 4 (PCN #27, Jan-Feb 2014), I offered a simplified definition of the term “living fossils”—organisms

that haven’t changed since their first appearance in the fossil

record—plus an expanded definition, namely, that at various points in

time “all” organisms were living fossils(as exemplified in Figs. 4-7).

It has been my

hope in this series to provide documented proof that three fields of

science have been misleading the public regarding fossils—biology,

paleontology, and anthropology—and that these three fields, unlike

other sciences, depend upon preventing

(continued on page 14)

|

Genus

|

Former living fossils |

Range

|

Fossils recovered in situ by the author

|

Athyris

|

Unchanged

201 million years

Silurian–Triassic;

422.9–221.5 MYA |

Worldwide

|

1/2" w (1.2 cm)

Athyris; rec. in situ by author; Devonian;

Arkona, Ontario |

Schizophoria

|

Unchanged

191 million years

Silurian–Permian;

443.7–252.3 MYA |

Worldwide

|

1 1/8" w (2.9 cm)

Schizophoria; rec. in situ by author; Dev.;

Arkona, Ontario |

Rhipidomella

|

Unchanged

187 million years

Silurian–Upper Permian;

439.0–252.3 MYA |

Worldwide

|

11/16" w (1.8 cm)

Rhipidomella; rec. in situ by author; Dev.;

Sylvania, Ohio |

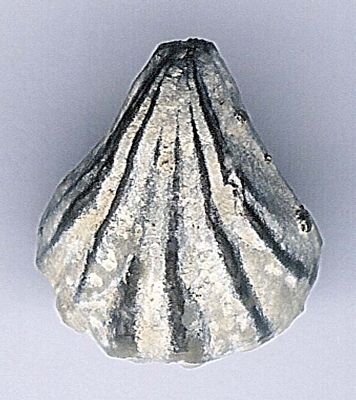

Leiorhynchus

(Eumetabolotoechia) |

Unchanged

150 million years

Devonian–Permian;

409.1–259.0 MYA |

Worldwide

|

3/4" w(1.9 cm)

Leiorhynchus; rec. in situ by author; Dev.;

Arkona, Ontario |

Leptaena

|

Unchanged

135 million years

Ordovician–Mississippian;

471.8–336.0 MYA |

Worldwide

|

1 1/8" w (2.3 cm)

Leptaena; in situ by author; Ordovician;

northern Kentucky |

Echinoconchus

|

Unchanged

131 million years

Devonian–Permian;

383.7–252.3 MYA |

Worldwide

|

1 3/16" w (3 cm)

Echinoconchus in situ; author; Mississippian;

Iuka, Mississippi |

Composita

|

Unchanged

127 million years

Devonian–Permian;

379.5–252.3 MYA |

Worldwide

|

11/16" w (1.8 cm)

Composita; in situ by author, Pennsylvanian;

Paris, Illinois |

Atrypa

|

Unchanged

121 million years

Ordovician–Mississippian;

457.5–336.0 MYA |

Worldwide

|

1 1/4" w (3.1 cm)

Atrypa; rec. in situ by author, Devonian;

Rogers City, MI |

Punctospirifer

|

Unchanged

112 million years

Devonian–Permian;

364.7–252.3 MYA |

Worldwide

|

1/2" w (1.3 cm)

Punctospirifer; in situ by author, Pennsylvanian;

Paris, Illinois |

Marginifera*

*Compare age range with Neospirifer |

Unchanged

109 million years

Mississippian–Triassic;

360.7–251.3 MYA |

Worldwide

|

9/16" w (1.5 cm)

Marginifera; in situ by author, Pennsylvanian;

Paris, Illinois |

*Neospirifer

*Compare age range with Marginifera |

Unchanged

108 million years

Mississippian–Permian;

360.7–252.3 MYA |

Worldwide

|

1 5/16" w (3.3 cm)

Neospirifer; in situ by author, Pennsylvanian;

Paris, Illinois |

|

Fig. 5.

Continuing from Fig. 4, more examples of well established one-time

living fossils with no morphing between genera. Specific date ranges

are agreed to by international consensus.

|

|

![Chatellperronian [Neanderthal] Rhynchonellid REDRAW [aft-Leroi-Gourhan.gif](images/Chatellperronian%20%5BNeanderthal%5D%20Rhynchonellid%20REDRAW%20%5Baft-Leroi-Gourhan.gif)